June 8 & 24, 2001. BIS-Gold Price Fixing Case: Update on the Battle of the Briefs

On May 25, 2001, the Department of Justice moved for leave to file reply memoranda on behalf of Secretary O’Neill and Chairman Greenspan. On May 29, the Bank for International Settlements filed a similar motion. All three motions were accompanied by the proposed memoranda, which are posted at www.zealllc.com/howedef.htm. On May 31, I filed a Qualified Opposition to Reply Memoranda of the DOJ and BIS, which included a request that my opposition be accepted as a surreply if the reply memoranda were allowed. On June 4, the court granted leave to file the DOJ memoranda, denied leave to file the BIS memorandum, and denied leave to file a surreply. Meanwhile, on June 1, J. P. Morgan Chase and Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank also filed motions for leave to file accompanying reply memoranda. Citigroup joined in and adopted these memoranda on June 5. All these documents, too, are posted at Zeal LLC. On June 8, I filed an Opposition to Reply Memoranda of the Bullion Banks, which like my earlier qualified opposition also contained a proposed surreply.

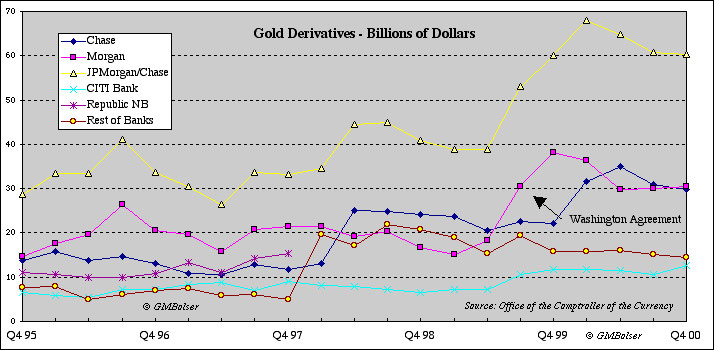

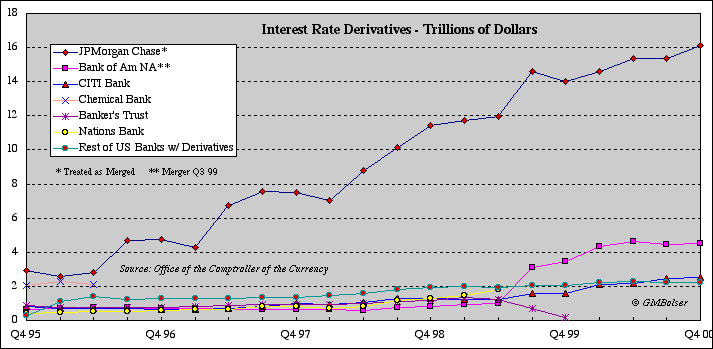

The factual grounds for the legal argument made in the surreply portion of that opposition is dramatized in the following two charts, courtesy of Mike Bolser:

On June 20, 2001, the court entered the following order on the face of J. P. Morgan Chase’s motion to file a reply memorandum: “Motion allowed, and in addition, leave is granted plaintiff to file surreply submitted with his opposition to this motion.” The court also allowed the similar motion of Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank. As a result of these rulings, the argument contained in part II of my opposition — and illustrated in the charts above — is now a formal part of the record. If the court had denied the bullion banks’ motions, my opposition as a surreply would have become moot. Since the argument in the surreply was not contained in my original opposition and includes citations to new material, including the Federal Reserve Board’s decision allowing the Chase/Morgan merger, the cumulative result of the court’s rulings strikes me as probably a net plus.

May 28, 2001. The Last Train Out

Because Rick made the last train out of Paris, he lived to fight another day, and in the interim provided grist for a great movie, Casablanca. Those were years when prescient men and women all over Europe were running for the proverbial last train out, sometimes just a few steps ahead of the Gestapo. Some made it, as in The Sound of Music. Some did not, among them Natalie Jastrow Henry in Herman Wouk’s The Winds of War. Some chose to stay in place and await their fate. But most only dimly understood, if at all, the historic currents about to redirect their lives. Only later did they appreciate that of all the trains then chugging over the Continent, some were vehicles of escape to freedom and life while others bore their passengers to unbelievable depravity and death.

It is human nature to think that tomorrow will be much like today, that history progresses in a more or less linear fashion. Great discontinuities boggle the mind. My friend Adam Hamilton has just written a piece, Gold Prepares to Erupt, comparing the current monetary and investment climate to ancient Pompeii just before its immolation by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Adam concludes: “We are now observing initial pressure-blowoff warning signs in gold, and the great financial lessons of history coupled with the immutable laws of free-market economics ensure gold is preparing for a spectacular price eruption.”

Market or volcanic eruptions are notoriously difficult to predict. The forces that lead to them, however, are somewhat easier to observe. Anyone interested in gold who has not yet read Frank Veneroso’s presentation at the GATA conference in Durban on May 10, 2001, should do so at once. Gold speaks primarily through flows of physical metal, gold prices in various world markets, lease rates, and general conditions in the gold mining industry. Frank is almost certainly the world’s leading authority on gold flows, including the huge amount of gold that central banks have recklessly loaned out over the past decade and that now represents an alarmingly large short physical position overhanging the world financial system.

In recent months my commentaries have been limited by the demands of my litigation against the gold price fixing cabal. Last Friday government lawyers for Paul O’Neill, Secretary of the Treasury, and Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, dropped on me some weekend reading consisting of reply briefs they want to file in response to the opposition that I filed to their motions to dismiss. I understand that the Bank for International Settlements may also move for leave to file a reply brief. These reply briefs, which are not allowed as of right, come more than five weeks after I filed my opposition. In the appellate courts, reply briefs that are allowed as of right must usually be filed within two weeks of the principal brief to which they respond. So I ask myself: What has suddenly prompted this urge to file reply briefs? Is it just the government moving at its typical glacial pace, or is something else going on?

On Saturday, May 26, GATA chairman Bill Murphy received a second letter from Lawrence B. Lindsay, Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and generally regarded as President Bush’s top economic adviser. While Bill has not revealed publicly the exact contents of the letter, he has revealed its date: May 30, 2001. A postdated letter from the White House strikes me as a bit unusual.

These strange emanations from Washington may be nothing more than government doing what it does best: chasing its own tail. But they could reflect some more rational purpose that cannot yet be fully discerned. Over the past few weeks, amidst talk of a Gold Syndicate taking on the Gold Cabal, the gold market has displayed a decidedly different and more bullish tone. Rumor has it that the Gold Syndicate includes the Chinese, Middle Eastern interests and George Soros, who apparently plans to make another billion dollars at the expense of the Bank of England. Certainly there has been increased media coverage of GATA, much but not all of it generated by the conference in Durban. Lease rates have displayed unusual volatility and inversions. The possibility of a delivery squeeze on the COMEX June gold contract looms ever larger.

Given the fundamentals of the current international financial picture, gold looks ready to resume its historic role as the financial asset of last resort, the only financial asset that is not another’s liability. All these recent straws in the wind sound like the gold train blowing its whistle and preparing to leave the station. When it does, the dollar-dominated financial world we have come to assume will change forever. Its great hero, Alan Greenspan, will take his rightful place in history alongside John Law. Don’t miss the gold train. It is one train that even my FJ1200 superbike can’t catch.

April 19, 2001. BIS-Gold Price Fixing Case: Patriots’ Day Filings

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled;

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard ’round the world.

–Ralph Waldo Emerson

The Statement of Facts in the Consolidated Opposition contains some interesting new evidence, which may be accessed directly from the following link: Gold Swaps by the ESF.

March 21, 2001. BIS-Gold Price Fixing Case: Update

The schedule for responses described in my March 9, 2001, status report has been allowed by the court. Pursuant thereto, on March 15 the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) filed two motions, each with a separate supporting memorandum, on behalf of the Secretary of the Treasury: (1) to substitute Paul O’Neill, the current secretary, for former secretary Lawrence H. Summers; and (2) to dismiss the case both as against the Secretary of the Treasury in his official capacity and as against Mr. Summers individually. The DOJ has advised me that it does not represent Mr. Summers personally at this time, nor is the DOJ currently representing any of the other federal defendants. In addition, the DOJ has indicated that it does not have any objection to its court filings being posted online, although as yet it has not provided electronic copies. However, Adam Hamilton has taken a hard copies of the DOJ’s memoranda, scanned them, and converted both into PDF format for virtually exact online reproduction. These memoranda may now be viewed at a special section of Adam’s site: www.zealllc.com/howedef.htm.

For a number of reasons, I am not going to comment upon or otherwise discuss the motions and memoranda filed by the DOJ or any other defendants until I file my opposition papers on April 30. They will be posted here at The Golden Sextant as soon after they are filed in court as I can convert them to HTML format. In the meantime, I intend to do whatever I can to facilitate the posting at Adam’s site of the defendants’ memoranda as they are received, and I extend to Adam and his associates at Zeal LLC my sincere thanks for their efforts to bring all sides of this case to the public.

March 9, 2001. BIS-Gold Price Fixing Case: Status Report

Because there is some confusion over what is scheduled to happen on March 15, and also because all parties to the case have filed a joint motion with the court to establish a slightly modified schedule, I am providing this status report, which also should help to reduce somewhat my e-mail traffic.

The normal rules of procedure in federal district courts require a defendant to file a written response to a complaint within a certain time period, which may vary depending on the type of defendant (e.g., domestic, foreign, government) and the manner of service. Generally speaking, these responses may be of two types: (1) an answer to the complaint, addressing by numbered paragraph each of its allegations, and raising any other defenses or counterclaims; or (2) a motion to dismiss, raising legal defenses that would prevent the court from granting any relief even assuming the factual allegations of the complaint are true. Defendants who file motions to dismiss are not required to file answers until after their motions to dismiss are heard and determined. A motion to dismiss must be accompanied at the time of filing by a brief supporting the motion and citing the legal authorities therefor. When a motion to dismiss is filed, the plaintiff is allowed time to file an opposition containing a statement of reasons why the motion should not be allowed, the defendant required to answer, and the case allowed to proceed.

It is quite normal for defendants in complex cases to request extensions of time to respond, and just as normal for plaintiffs to assent to these requests. This week all parties in my case, including me, filed a joint motion with the court requesting that the various defendants be allowed until the following dates to file their responses: March 15 for the Secretary of the Treasury; March 30 for all other defendants except William J. McDonough; and April 10 for Mr. McDonough. In addition, the joint motion requests that the plaintiff be allowed until April 30 to file his oppositions to any motions to dismiss or other defensive motions filed by the defendants pursuant to the agreed schedule.

It is my expectation based on discussions with the attorneys for the various defendants that all of them are planning to file motions to dismiss. Typically, after the filing of motions to dismiss and the oppositions thereto, the court will set a hearing date for oral argument on the motions. At the hearing, the court may rule on the motions, or parts thereof, from the bench, but normally, especially in a complex case, the court will take the motions under advisement and issue a written ruling and opinion later. Courts control their own schedules, which are affected by many different considerations, so it is not possible to predict with much precision likely dates for a hearing or a ruling. However, I will continue to post periodic status reports as appropriate, and I am working on arrangements to make available online all significant court filings. In any event, my own oppositions will be posted here at The Golden Sextant, as will notice of any important court hearings.

February 20, 2001. Hidden Faces of Modern Imperialism: AngloGold, Barrick and the BIS

Shades of Cecil Rhodes and Alfred Beit. At the Indaba African Mining Conference in Cape Town, Kelvin Williams of AngloGold, South Africa’s largest gold producer, used his turn at the podium to take a gratuitous swipe at GATA: “Forget for the moment about the notion of a conspiracy against gold, and worldwide plots between central bankers here, there and everywhere. We face a physical overhang of the metal….”

Huh? Annual new mine production has peaked at around 2500 tonnes. Annual demand for gold now exceeds 4500 metric tonnes. Last week, the World Gold Council reported that demand in the markets it surveys reached almost 900 tonnes in the last quarter of 2000, the highest level of quarterly demand ever recorded by the WGC. For years now, the ever growing gap between new mine supply and demand has been filled by a combination of scrap recovery, official sales and, most importantly, gold borrowed from central banks and sold into the market, much of it pursuant to hedging programs of producers like AngloGold. Its continuing policy, restated by Williams at Indaba, is to hedge mostly through forward sales up to one-half of its production for the next five years.

With financial and editorial support from “South Africans for a free gold market,” GATA responded to AngloGold’s jibe through a full page ad in Business Day, the principal financial newspaper in South Africa. The ad pointedly questioned whether AngloGold’s role in driving down gold prices through heavy forward selling should be rewarded by allowing it to purchase Gold Fields, the country’s second largest gold producer, which last week announced that it had used recent weakness in gold prices to close out its remaining forward sales.

AngloGold is 53% owned by Anglo American PLC, the international mining and natural resources conglomerate that also controls Anglo American Platinum, the largest producer of PGM’s outside Russia, and De Beers group, the world diamond cartel built by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer and his son Harry after the elder Oppenheimer in 1929 seized control of the corporate empire left by Cecil Rhodes. See Susan Emerling, “Not forever” (www.salon.com). Anglo American has recently announced a reorganization of the De Beers companies amidst reports that De Beers wants to shed the image of a cartel in order to improve its access to the American market. Once, when asked whether he preferred diamonds or gold, Sir Harry replied: “Diamonds, every time. People buy diamonds out of vanity. They buy gold because they are too stupid to think of any other monetary system which will work.” Today gold is a loss leader for Anglo American — cheap settings for its more profitable diamonds.

Barrick Gold is also rumored to have designs on Gold Fields, possibly in conjunction with AngloGold. Barrick is controlled by Canadian financier Peter Munk through TrizecHahn Corporation, his flagship international real estate development company. Like AngloGold, Barrick operates an aggressive forward sales program, including the writing of call options to sweeten the returns from hedging. This tactic is particularly dangerous absent a high level of confidence in continued low gold prices. Since 1997, TrizecHahn has reduced its stake in Barrick from about 16% to under 8%, following earlier large dispositions of Barrick shares by Horsham, TrizecHahn’s predecessor. On a split-adjusted basis, Barrick’s share price peaked at more than twice its current level in early 1994 and again in early 1996, making all these sales by Munk’s holding companies appear prescient indeed.

As parts of larger corporate empires with their major interests outside gold, AngloGold and Barrick differ from other gold mining companies in a way that helps to explain their aggressive hedging policies. The overall profits of their parent companies, Anglo American and TrizecHahn, are far more dependent on continued strength in the G-10 economies than on higher gold prices. One analyst estimates that gold at $600/ounce would add one full percentage point to the economic growth rate of South Africa, where currently each gold miner supports an average of 11 to 12 others. But however warranted by fundamentals, a price increase of this magnitude would unmask the short gold position of the bullion banks, threatening the very consequences that so frightened Eddie George, Governor of the Bank of England, in the wake of the Washington Agreement. See Complaint, paragraph 55.

Accordingly, viewed in the larger context of Anglo American’s interests rather than just AngloGold’s, it is not surprising that Kelvin Williams at Indaba described a shortage of physical gold as a glut, or that he tried to deflect the blame for low gold prices away from their true source: the G-10 central banks operating a price fixing scheme through the Bank for International Settlements in an increasingly desperate war against gold. Leaders of struggling new democratic regimes in the gold producing nations of Africa should not fall for the G-10’s shills. Rather, as African leaders evaluate the evidence of gold price fixing adduced by the GATA impi, they should be guided by Thomas Jefferson’s remark to James Madison: “Resort is had to ridicule only when reason is against us.” After all, the author of the Declaration of Independence and the principal draftsman of the Constitution have a record for democratic nation building that is hard to beat.

For many gold bugs, the transition of the BIS from a European ally to an important tool of official Anglo-American gold bashing is perhaps the most surprising and disheartening development of the past few years. As reflected in the transcript of the Federal Open Market Committee’s conference call on July 20, 1994, this transformation stems from the Treaty of Maastricht, which put the European Monetary Institute followed by the European Central Bank on track to replace the BIS as the primary vehicle for joint action and cooperation among European central banks. To avoid being sidelined as irrelevant, the BIS undertook to reinvent itself as a global financial institution, an effort which the ever opportunistic Alan Greenspan was only too pleased to support. As the Fed chairman explained to the FOMC:

Up until the Maastrich Treaty, our relationships with the BIS seemed to be appropriately constrained to our periodic visits over there to deal with the G-10 on a consultative basis and to be involved with a number of their committees, but to have no involvement at all with the actual management of the BIS. With the advent of the Maastrich Treaty and the development of the European Monetary Institute, the potential of the BIS being effectively neutered because of the overlap in jurisdictions of the EMI and the BIS has led the BIS to move toward a much more global role, one that anticipates inviting a significant number of non-European members, 10 to 25 as I recall the range, to become members of the BIS. That would significantly alter its character from a largely though not exclusively European managed operation to one which is far more global in nature. It is possible, perhaps probable, that the BIS as a consequence will become a much larger player on the world scene. It was our judgment that it would be advisable for us to be involved in the managerial changes that are about to be initiated rather than to stay on the sidelines, as we chose to do through all those decades when we did not want to get involved with a European-type international organization. In contradistinction to that, we think it is important to be an active player in the development of this institution to make certain that we as the principal international financial player have a significant amount to say in the evolution of the institution. That’s the basis upon which this decision has been made here at the Board, and it was one which we probably would not have addressed in any meaningful way had not the altered nature of the BIS itself become imminent.

A few days after this FOMC briefing, the BIS announced that Messrs. Greenspan and McDonough would assume the two seats on its board reserved for the American issue, and that the governors of the Bank of Canada and Bank of Japan had also been elected to the board. Thus, with inclusion of the United States, the board would henceforth consist of the G-10 countries. As the International Monetary Fund has already demonstrated, nothing is more dangerous to economic growth and democratic progress in developing nations than an obsolete international financial institution cut adrift from the developed world and left to save itself by trying to help the less developed. No one ever seems to ask how the developed world developed without these institutions.

Like the IMF, the BIS sails today on a monetary course for which it was neither designed nor intended. Article 20 of its Statutes still commands: “The operations of the Bank for its own account shall only be carried out in currencies which in the opinion of the Board satisfy the practical requirements of the gold or gold exchange standard.” Among the standing committees of the BIS is the Committee on Gold and Foreign Exchange, sometimes referred to as the Committee of Experts on Gold and Foreign Exchange or the G-10 Committee on Gold and Foreign Exchange. Exactly what this committee does in the area of gold, including why it has not suggested amendment or deletion of Article 20, is an obvious subject for discovery in my lawsuit, as well as for direct inquiry by several gold producing nations of Africa which are members of the BIS, especially South Africa.

One clue is (or was) available online. Until about two weeks ago, the last sentence of the first paragraph of the biographical summary for Peter R. Fisher, head of the New York Fed’s markets group, read: “He also is a member of the bank’s Management Committee and serves on the Gold and Foreign Exchange Committee of the G-10 central banks.” On February 6, 2001, this sentence was deleted while the rest of the biography remained unchanged. (A “Google” search for “Peter Fisher committee gold” will still turn up a reference to the missing sentence.) Fisher is widely reported to have played a major role in the Fed-orchestrated rescue of Long Term Capital Management, which according to reliable sources was short 300 to 400 tonnes of gold. Hard to believe that the presumed captain of the Plunge Protection Team has lost these prestigious committee appointments, and only a few days after a GATA supporter found his online bio, too.

Speaking of the New York Fed, after dropping to low or negligible levels from April through August, withdrawals of gold from earmarked foreign and international accounts have run at a heavy pace in the months since: 40 tonnes in September, 41 in October, and 44 in November. Added to the heavy outflows in the first quarter, total withdrawals in the first 11 months of 2000 equal 315 tonnes, or more than the full year totals of 302 tonnes for 1999 and 309 tonnes for 1998. My hunch is that much of this official outflow is IMF gold deposited with — and loaned out by — the BIS. I also suspect that part of the reason for the compulsory freeze-out of the BIS’s private shareholders is to avoid publication of annual financial reports that might disclose some of this activity. See, e.g., commentary dated June 11, 2000, Central Banks vs. Gold: Winning Battles but Losing the War? (This commentary also contains a chart showing monthly outflows of foreign earmarked gold from January 1997 through March 2000.)

As shown graphically in a prior commentary, Cycles of Manipulation: COMEX Option Expiration Days and BOE Auctions, the Bank of England’s gold auctions are on the same bimonthly cycle as COMEX gold options and futures. Don Lindley reports that immediately following the last auction on January 23, his “option cube” turned from a bullish bias toward $280/ounce to sharply bearish, suggesting a decline to $260 or lower. The basic pattern seems to be that the auctions provide the delta for the bullion banks to write calls, which traders then use to support bear raids on the futures. In any event, the timing of the British auctions betrays their true purpose.

In a recent article, NY Strangulation of World Gold Market – 1 Year, Harry Clawar updates his data on gold price increases overseas and their cancellation by selling on the COMEX. For the year beginning January 25, 2000, when his study started, net overseas price increases amounted to $160/ounce, while net decreases in New York equaled $173/ounce. Meanwhile, as shown in the Gold Market Regression Charts that Mike Bolser continues to update as new data becomes available, the intuitively contradictory trends of strong physical demand and shrinking markets for paper gold continue to manifest themselves. The latter trend is also quite apparent in reduced turnover and open interest in gold contracts on the TOCOM, which Mike does not chart.

Richard Russell has been watching markets and writing about them almost since the day he returned from World War II service in bombers over Europe. His Dow Theory Letters is among the oldest and most successful investment letters. On January 24, 2001, he wrote: “I don’t, as a rule, believe in manipulation in the markets, but if there are two areas of manipulation they are (1) gold – everytime gold sticks it’s little yellow head up, someone, somewhere – brings a hammer down on that poor head. Ouch.” Turning to area (2), he continued: “The Dow and the S&P – watch the last 15 minutes of every session. Someone, probably a fund or a brokerage house, moves in and buys just enough to move the Dow up 15 to 25 points and in the same percentages with the S&P.”

Linked, coordinated manipulation of gold and stocks poses the danger that disclosure of rigging in one market will expose it in the other. In that event, spiking gold with a sinking dollar and a collapsing Dow in an already slowing economy will be two sides of the same coin. Given egregious misvaluations of both gold and stocks plus a gargantuan trade deficit with no historical precedent, the ingredients are at hand for an economic crisis on a scale not seen since the Great Depression. The scenario from Gold or Dross? Political Derivatives in Campaign 2000 is looming ever larger.

As the Germans advanced into Poland, W. H. Auden penned September 1, 1939 (“As the clever hopes expire / Of a low dishonest decade”). One stanza’s final line (“We must love one another or die”) was so misinterpreted and misused that the poet removed the entire stanza from the 1945 collection of his works. Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 presidential campaign against Barry Goldwater ran a television spot based on the deleted stanza. Starting with a young girl pulling petals from a daisy while a voice intoned the countdown, the ad ended with a nuclear mushroom cloud and the voice misquoting the final line. After President Johnson put an army of over half a million men into Vietnam, Auden struck the whole poem from subsequent editions of his works.

In today’s world, where the imperatives of power and prosperity in the developed nations regularly trump concern for the less developed, September 1, 1939 — in lines never changed nor repudiated — speaks hauntingly to the G-10 governments and their satellite international financial institutions:

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism’s face

And the international wrong.

Not until eighty years after the war began did Thomas Pakenham publish his authoritative history, The Boer War (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1979; Abacus paperback edition, 1992, reprinted 2000, to which all page cites refer). Relying on material largely unavailable earlier, Pakenham emphasizes at the outset that he uncovered four new themes. Two of them are particularly relevant today, as is a third point summarized by the heading — “Milner’s War” — given to Part 1 of the book.

Cecil Rhodes conceived and funded the notorious Jameson Raid, now generally perceived as the war’s opening battle although it preceded the declaration of war by almost four years. However, prior historians assumed that Rhodes, Alfred Beit and Julius Wernher, who collectively controlled the richest gold mines of the Rand, were not directly involved in causing the war in 1899. “But directly concerned they were,” says Pakenham (p. xvi), who adds (pp. xvi-xvii): “I have found evidence here of an informal alliance between Sir Alfred Milner, the British High Commissioner, and the firm of Wernher-Beit, the dominant Rand mining house. It was this secret alliance, I believe, that gave Milner the strength to precipitate the war.”

The gold mining companies were prepared to endure the certain disruptions and costs of war to secure two important long term advantages which they expected a British administration to deliver: (1) more favorable tax treatment than under President Kruger’s Boer government; and (2) a plentiful and reliable supply of cheap black labor. “What made [the gold mining moguls] such wonderful allies was that they repeated over and over again the dictum that there would be no war — that is, if Britain called Kruger’s bluff and sent out the troops,” writes Pakenham (p. 89). He adds (id.): “Possibly Rhodes believed his own forecasts. But Beit, Wernher and Fitzpatrick knew the Boers. The despatch of British troops would precipitate war.”

The second new theme underlined by Pakenham is that the heaviest burden of what contemporaries labeled a “white man’s war” fell on South Africa’s black and coloured populations. Not that the main protagonists did not suffer enormously. In men, money and materiel, it was Britain’s costliest war since the defeat of Napoleon, not to be outdone until World War I. Relatively speaking, the costs to the Boers of their “Second War of Independence” were even higher. But, says Pakenham (p. xvii): “In general it was the Africans who had to pay the heaviest price in the war and its aftermath.” Adding insult to injury, in the Treaty of Vereeniging ending the conflict, the British agreed to a provision postponing the franchise for blacks and coloureds until after the introduction of self-government, when of course the local white population would not grant it.

Perhaps the most startling point to emerge from Pakenham’s book is that absent one man, Alfred Milner, British viceroy of South Africa, the war would never have occurred. Motivated by his belief in Britain’s imperial role and a personal ambition to rank among its heroes, Milner hoodwinked his own government into waging war over a controversy that it desired to settle by negotiation and compromise. The public justification for the war — to secure the franchise and fair treatment for the Uitlanders, white and mostly British immigrants who had followed the gold rush into the Transvaal — was largely a sham. Worse, with the aid of a few like-minded friends as well as the gold mining interests, Milner deceived his superiors, including the Colonial Secretary and the Prime Minister, regarding the actual course and content of his negotiations with the Boer government. Referring to the war as “Milner’s War” is no exaggeration; it is the simple truth.

About the time that he assumed office, President Kennedy remarked that modern statesmen ought to read Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August. His successful handling of the Cuban missile crisis suggests that he profited from his own advice. Pakenham’s The Boer War is similar must reading for anyone concerned with modern South Africa or today’s gold market. Against this history, the gold price fixing allegations of my Complaint are scarcely far-fetched. Rather, they read like a new variation on an old theme: the plunder of South Africa’s gold reserves for the primary use and benefit of British and other outside interests.

The gold cabal orchestrated by top officials of the Clinton administration and the Blair government, with maestro Alan Greenspan and assistant Eddie George directing the BIS ensemble, bears uncanny resemblance to the machinations that brought on the Boer War. Motivated by ambition and greed, cloaked in deceit, both schemes set political power and private profits as their ultimate goal. Both required cunning, Machiavellian leadership. Elements of Milner are readily apparent in Mr. Greenspan, self-described as “among those of us engaged to replace [the gold standard],” that is, to create the economic version of alchemy. Reeking of world class hypocrisy, the IMF gold sales were no more proposed for the benefit of poor countries in sub-Saharan Africa than the Boer War was prosecuted to secure the franchise and other democratic rights for the Uitlanders.

When the British lion roared its defiance of Hitler through the mouth of Winston Churchill, South Africa stood by it notwithstanding painful memories of the Boer War. But the British lion is not like the African lion from whose paw Androcles pulled the thorn. Rather, the British lion displays today the same morality that it seems to have taught its most famous Rhodes scholar, recently departed from the White House: “What have you done for me lately?”

Speaking at the Indaba African Mining Conference last week, one African minister warned that democratic governments cannot expect to take permanent root in developing countries unless they deliver measurably improved living conditions within reasonable time frames. Nor can they succeed unless they provide the basic building blocks of republican democracy: the rule of law, free markets and sound money. Gold mining remains a mainstay of the South African economy, which dominates that of the whole sub-Saharan region. It is hard to imagine anything that would do more to stimulate economic growth in the area than an increase in gold prices from the low levels set by manipulation to their more natural equilibrium now estimated by some at around $500/oz.

To most Americans, strong U.S. support both for the new multiracial government in South Africa and for other African nations trying to move toward stable democratic regimes appears unquestionably in the national interest. Few would accept that U.S. policy in the region should be hijacked by the Fed for the benefit of a few bullion banks, let alone that the Fed and the Exchange Stabilization Fund should conspire with the BIS and the British government to manipulate the free market price of gold. On the birthday of America’s Great Emancipator, the new administration in Washington should make clear that its policies toward South Africa and its neighbors will be governed by the law, the Constitution and the national interest.

But it would be a mistake to conclude that the future of South Africa or its gold mining industry rests in the hands of officials in Washington, London, or elsewhere outside South Africa. It is a nation rich in human as well as natural resources, and possessed of considerable spiritual resources as well. More like the United States than Canada or Australia, South Africa never lived comfortably with the British lion, and completely withdrew from the Commonwealth in 1961. Its great military battles are its own, not engagements in foreign lands on behalf of the Crown.

Of all the smaller nations in the world, South Africa is perhaps best positioned to withdraw from the IMF and reestablish for itself a monetary system linked to gold. In that event, South Africa’s national patrimony would not be dumped into the world market at low prices rigged by others. Nor would its currency be battered below any reasonable measure of its purchasing power parity versus others. Rather, its gold would have to be earned by exports of goods or services or purchased for investment on capital account. By adopting a monetary system like that on which most of the developed world developed, including the United States, South Africa might reasonably look forward to following a similar path, and, at long last, to extinction of the British lion on the Rand.