MPEG COMMENTARY – Page 21

June 18, 2002. Fork in the Road: Appeal of Right or the Right Appeal

A decade ago in my essay The Golden Sextant, I urged the adoption of a modernized gold standard, both to bring the U.S. monetary system back into conformity with the Constitution and to reform the international monetary system to make it fair to all nations, small and large alike. At that time, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War created circumstances conducive to worldwide monetary reform, including restoring gold to a more central role in the international payments system. However, U.S. monetary nationalism and official hostility to gold dating back to the New Deal remained an insurmountable bar.

Modern governments have proven incapable of managing even bastardized versions of the gold standard, either domestically or internationally. The Federal Reserve, created in 1913 to improve domestic operation of the classical gold standard, destroyed it in just 20 years, partly due to a misguided effort to help the Bank of England remain on the gold exchange standard after World War I. See A. Greenspan, “Gold and Economic Freedom” (reprinted in A. Rand, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, available online at www.gold-eagle.com/greenspan041998.html).

Nor have international financial institutions proved any more capable of maintaining official linkages to gold, particularly in the face of opposition from major powers. The Bank for International Settlements was created in part to facilitate operation of the gold exchange standard, which soon thereafter met its demise. The Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates linked to the dollar and gold lasted less than 30 years, making the International Monetary Fund ultimately no more successful than the BIS in carrying out its original monetary charter. Contrary to the hopes and expectations of many, far from representing an attempt to establish a sound currency with some credible connection to gold, the euro is proving little more than an effort to horn in on the fiat dollar’s reserve currency franchise.

At the same time, the euro has also undermined the argument that issuing money is an essential element of national sovereignty. France is France without the franc; Germany is Germany without the mark; and soon Britain will be Britain without the pound. Indeed, the euro nations are surrendering more of their monetary sovereignty to the European Central Bank than they were ever required to give up by adhering to the rules of the classical gold standard.

Breach of Monetary Trust. Although the United States continues to issue a national currency, it does not “coin money” within the meaning of the Constitution, which grants Congress the power: “To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures.” As described by the Supreme Court prior to the Civil War in United States v. Marigold, 50 U.S. (9 How.) 261, 262-263 (1849), the government’s monetary powers rest on a different basis from its powers over commerce (id. at 263):

They appertain rather to the execution of an important trust invested by the constitution, and to the obligation to fulfill that trust on the part of the government, namely, the trust and duty of creating and maintaining a uniform and pure metallic standard of value throughout the Union. The power of coining money and of regulating its value was delegated to congress by the constitution for the very purpose, as assigned by the framers of that instrument, of creating and preserving the uniformity and purity of such a standard of value … . [Emphasis supplied.]

Long before his appointment to the Supreme Court, Justice Holmes wrote a series of favorable comments on Justice Field’s dissent in the Legal Tender Cases, 79 U.S. (12 Wall.) 457, 649-651 (1870). 4 Am. Law Rev. 768 (1870); 7 Am. Law Rev. 147 (1872); 1 Kent’s Commentaries (12th ed.) 254 (1873). In the latter, Holmes set forth in detail what he considered an “unanswerable” argument:

The question is not whether the Constitution prohibits the exercise of the power [to declare paper a legal tender], but whether it grants it; of course, a power as to which the Constitution is silent, may be given by implication as a necessary or proper means of carrying out other powers which are expressly conferred; but it is hard to see how a limited power, which is expressly given, and which does not come up to the desired height, can be enlarged as an incident to some other express power; an express grant seems to exclude implications; the power to “coin money” means to strike off metallic medals (coin) and to make those medals legal tender (money); if the Constitution says expressly that Congress shall have power to make metallic legal tender, how can it be taken to say by implication that Congress shall have power to make paper legal tender?

Today the government does not coin money in the constitutional sense because there is no official metallic standard of value. The only metallic standards of value are the market prices for gold and silver. In short, rather than perform their trust and duty under the coinage clause, all three branches of the government behave as if the Constitution contained an additional article:

Section 1. The banking Power of the United States shall be vested in one National Bank, and such inferior banks as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The National Bank shall have a Board of Governors consisting of a Chairman and not less than four other Governors.

Section 2. The President shall have Power to nominate and appoint, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, the Chairman and Governors of the National Bank, who shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, for Terms and at Compensation set by the Congress.

Section 3. The National Bank shall maintain the Value of gold and silver Coin at Rates established by the Congress.

Section 4. Whenever the Congress shall fail to exercise the Power to coin Money and to regulate the Value thereof, the National Bank shall have Power to emit Bills on the credit of the United States, and the Congress shall have Power to make these Bills a Tender in Payment of Debts. When exercising Power under this Section, the National Bank may trade in the Markets for gold and silver to affect the Value of its Bills.

Section 5. The National Bank shall not exercise Power under Section 4 except upon majority vote of a Committee, which shall be chaired by the Chairman, who shall have one Vote. The other Members of the Committee, each of whom shall have one Vote, shall be the other Governors of the National Bank and an equal number of Persons chosen by such private banks and in such manner as the Congress may by Law direct.

Section 6. The National Bank shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the President, to enter into Treaties, Alliances and other Arrangements with national banks of foreign States.

Section 7. The judicial Power under Article III shall not extend to reviewing acts of the National Bank, but whenever Bills issued under Section 4 are Legal Tender, the Congress shall increase the Compensation of Judges under Article III to adjust for Depreciation in the Value of the Bills.

An Appeal without Appeal. Politicians in democracies here and abroad need paper money to buy votes and to lend at least a superficial veneer of credibility to their promises. Economists think they can manage paper money to ensure prosperity although they are never in agreement on the exact steps required. Bankers require paper money in order to have a lender of last resort to bail them out of their mistakes. Thus the dynamics of a modern democracy conspire against sound money based on gold or silver. It represents a discipline that none of these powerful interests can stomach and against which all will combine and conspire.

Lord Keynes once referred to the classical gold standard as a “barbarous relic” (J. M. Keynes, Monetary Reform (Harcourt, Brace, 1924), p. 187). For political rather than economic reasons, he has proven correct. The gold standard is a relic of long ago times when free governments put maintaining official gold parities ahead of everything save national survival in time of war.

No President since Ronald Reagan has supported returning to the gold standard. In the present Congress the idea has just one advocate, Congressman Ron Paul (R-TX) (www.house.gov/paul/congrec/congrec2002/cr060502.htm). GATA’s initiatives to the political branches, including the May 2000 meeting with House Speaker Dennis Hastert (R-IL) (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/gata/message/454), correspondence with Senator Joseph Lieberman (D-CT) and other members of Congress (e.g., http://groups.yahoo.com/group/gata/message/346), and communications with White House chief economic advisor Laurence Lindsey (http://www.lemetropolecafe.com/pfv.cfm?pfvID=1536), have all proved unproductive.

Nor have the courts shown any inclination to derail the paper money juggernaught. See Petition for Certiorari in Walter W. Fischer v. City of Dover, N.H., et al., Supreme Court of the United States, No. 91-221. In connection with a similar petition in an earlier case (Howe v. United States, 632 F. Supp. 700 (D. Mass. 1986), aff’d per curiam, 802 F.2d 440 (CA1 1986), cert. denied, 479 U.S. 1066 (1987)), I asked Erwin N. Griswold, then a partner in a Washington, D.C., law firm, formerly U.S. Solicitor General, and before that longtime dean of Harvard Law School, to consider filing a amicus brief in my support. By letter to me dated October 29, 1986, he responded in part:

Although I appreciate the skill and energy with which you have proceeded in this matter, I do not feel that there is any way that I can participate in this matter. Although your contentions may have much economic or philosophic merit, it does not seem to me that there is any prospect that you can get the Supreme Court to consider them. The problem is, as I see it, essentially a “political” one, dealing, as it does, with a field into which the courts have been very reluctant to enter. I doubt that there is really very much more to be said, on the legal side, after the decision in the Gold Clause case, 294 U.S. 240 (1935).

Accepting Dean Griswold’s views on the futility of seeking judicial enforcement of the monetary provisions of the Constitution is even less inviting than bowing to Lord Keynes on the impracticality of the gold standard. As indicated in my last commentary, Judge Lindsay’s decision dismissing the gold price fixing case carefully avoids placing any limits on the government’s ability to manipulate gold prices. Like those of other federal district courts since 1971 involving the monetary provisions of the Constitution, his decision is constructed to facilitate what has become standard operating procedure for these cases in the appellate courts: summary affirmance without hearing or opinion by the court of appeals followed by denial of further review in the Supreme Court.

Accordingly, unlike the district court case, an appeal is unlikely to serve any educational or other useful purpose, and thus will not be taken. Progress in the real world cannot be built on a strategy of vain gestures. Nor, of course, can anything be achieved by giving up. Targeting the Dred Scott decision and foreshadowing more famous lines in his First Inaugural, Abraham Lincoln declared in an 1859 speech: “The people of these United States are the rightful masters of both congresses and courts, not to overthrow the Constitution, but to overthrow the men who pervert the Constitution.” What is now required on the money issue is a new, more practical approach, legal and political. The time has come to restructure the terms of the gold-as-money debate.

Right to the Use and Benefits of Specie. The monetary provisions of the Constitution plainly contemplate that citizens of the United States should be entitled as a matter of right to the use and benefits of gold and silver as “specie” or metallic money. As defined in The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia (Century Co., New York, 1912): “The use of specie as a measure of price is based upon the intrinsic value of the precious metals as commodities, which has diminished immensely since ancient times, but is comparatively stable for long periods under normal circumstances.” See chart, “The real price of gold, 1344-1999,” at www.sharelynx.net/Charts/600yeargoldprice.gif.

Although the constitutionality of gold confiscation was not directly at issue in the Gold Clause Cases, it was upheld in dictum in Nortz v. United States, 294 U.S. 317, 328 (1934), and thus stands in sharp contradiction to the assertion of this right. Accordingly, at least in the United States, the right to use gold and silver as specie cannot be securely established and protected without a constitutional amendment along the following lines:

Neither the Congress nor any State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge, burden, or otherwise discriminate against, the right of the people to the Use and Benefits of Specie, whether Silver or Gold, which shall always be freely exchangeable with other Moneys of any Kind.

By itself, the inability or refusal of the federal government to exercise its coinage power so as to establish and preserve a metallic standard of value does not prevent the use of gold or silver as specie as long as these metals are allowed to compete with national or other paper currencies on an equal footing. What is required is a free and nondiscriminatory market for money. Eliminate all sales and value added taxes on gold or silver. Treat gold and silver equally with other national currencies for purposes of state and federal income taxes. Allow investment and money market funds to hold gold or silver bullion under the same regulatory and tax framework as they hold dollars or foreign currencies.

In other nations, the right to use gold and silver as specie can be established by whatever means best suits their own particular legal systems. The key point is that the right of all people to hold their savings — the tangible fruits of their labor — in the historic monetary metals should be recognized and protected as a fundamental human right separate and apart from whatever particular national monetary system may be in place. At the international level, although the IMF prohibits member nations from linking their currencies to gold (see L. Parks, “The IMF Mandates Currency Instability,” available at www.fame.org), there is nothing in the IMF’s rules to prevent gold from circulating as specie at free market rates in parallel with national currencies.

Modern technology and the Internet are already working in favor of the increased use and availability of gold and silver as specie. See, e.g., www.GoldMoney.com and www.e-gold.com. Historically, the growth of bank notes and paper currencies developed in significant part due to their relative ease of use. Now many use plastic credit and debit cards almost to the exclusion of paper money for all but the smallest transactions. For unexplained reasons, Citibank just forced on me a “platinum” MasterCard in substitution for my prior “gold” card. From the perspective of technological feasibility, my next “gold” card could be a real gold card on an account denominated and maintained in gold.

The transition to the euro has demonstrated not just that national currencies may be replaced by a more universal medium, but also that they can quite easily be used in practice in parallel with another money. Even today, a visitor to France will find many prices quoted in francs as well as euros, a practice common in other euro area countries too. Memories of these dead national currencies will fade in time, but the system of dual price quotations could be adapted to pricing in euros and gold, thereby facilitating the use of real gold cards, an alternative that might be especially attractive to travelers from outside the euro area.

Fork in the Road to Ruin. Even if there were significant political support for a return to the gold standard, there is scant reason to believe that some new version of the gold standard would prove any more durable than the gold exchange standard or the Bretton Woods system, especially in the absence of any realistic prospect for judicial enforcement. What is more, the problem of setting a new official price would be extraordinarily difficult in light of the artificial suppression of gold prices over the past several years.

Rather than try to beat new life into the dead horses of the gold standard and the Constitution’s original monetary provisions, my best suggestion at this point is to follow the lead of GATA friend and supporter Hugo Salinas Price, who has long urged the use of silver as a parallel money in his native Mexico and the other nations of Latin America. See, e.g., “Basis for the Formation of a Latin American Common Market in Century 21,” at www.plata.com.mx/plata/plata/silver.htm; also http://groups.yahoo.com/group/gata/message/605). His approach applies equally to gold, which as the principal monetary metal is even more suitable for use as parallel money than silver.

Within this framework, the fight for sound money can be conducted on multiple levels but without a frontal attack on established monetary institutions. The principles of freedom are likely to be achieved more easily by redirecting the debate from the power of governments everywhere to establish and operate domestic monetary systems to the right of people everywhere to use gold and silver specie at their election in free and open competition with government managed currencies. It is easy, both practically and politically, to oppose a return to the gold standard; it is more difficult to oppose a free market for gold. Allowing private alternatives to often mismanaged government monopolies is an idea whose time has come. It applies to money with as much as force as to post offices and pensions.

In the developing world, as Hugo Salinas Price points out, increased use of gold or silver specie in parallel with national currencies offers even greater benefits. No longer would egregious government mismanagement of a nation’s currency necessarily destroy virtually all the savings of its citizens. As in the gold standard era, imprudent or corrupt governments could again go broke without taking the vast majority of their citizens with them into penury, as has happened most recently in Argentina despite its much heralded currency board based on the dollar.

With respect to the official sector, while gold in vault storage and gold receivables should be separately identified and publicly reported, central banks should not be otherwise constrained from using their gold as specie. The wholly artificial distinction between monetary and non-monetary gold promulgated by the IMF should be abandoned, and pacts like the Washington Agreement, which cannot in any event be effectively monitored for compliance, should be avoided.

Campaign for Free Gold. Obtaining a constitutional amendment is daunting and difficult task. But this ultimate goal need not be the only objective in a campaign to free gold and silver for use as specie. More easily achievable intermediate objectives include: (1) measures to promote greater transparency in the gold and silver markets and to provide more complete, reliable and timely information about them; and (2) creation of better investment vehicles for gold and silver bullion, including wider choices, easier access, and increased functionality. The constitutional right will be easier to achieve on the wings of widespread use.

A campaign to reestablish the use of gold and silver as specie is an endeavor behind which all major groups with an interest in these metals should be able to unite whatever their past differences and while maintaining their separate identities. As discussed in my last commentary, the gold price fixing case performed a useful function in exposing the official suppression of gold prices orchestrated by the central banks over the past several years. But litigation, not to mention litigation against the most powerful financial interests on the planet, is not everyone’s cup of tea, particularly when they have to deal on a regular basis with some of these same entities.

For GATA, the campaign to free gold would be a quite natural evolution, answering the question posed by D. McKay in “Quo vadis Gata?” (May 23, 2002) at www.theminingweb.com. Indeed, the GATA army could continue to build the “GATA” franchise even while metamorphosing from the Gold Anti-Trust Action Committee into the Gold and Truth Action Committee, a name that would better describe its new mission. For advocates of return to some form of gold standard, the campaign would be a first but essential step on the way to their ultimate goal should it at some future date become politically viable.

For the gold mining industry, the campaign would offer not just an effective way to highlight and promote the highest and best use of its product, but also the possibility of new business opportunities in gold banking. At a recent industry conference sponsored by the London Bullion Market Association, several participants remarked on the need to create more and better opportunities for investment in bullion itself, including through electronic means. See T. Calandra, “Better on Weather than Gold’s Price,” www.CBS MarketWatch.com (June 11, 2002).

Winston Churchill once observed: “The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.” As discussed in prior commentaries (see, e.g., Gold: Can’t Bank with It; Can’t Bank without It!), gold banking as presently conducted violates prudential rules developed over several centuries of experience. When the pyramid of gold derivatives collapses, as it inevitably must, existing players in gold banking — the central banks and most major bullion banks — will be deservedly discredited and gold banking ripe for substantial restructuring, quite possibly outside the confines of existing or traditional banking institutions. The gold mining industry may well have the first opportunity since the ancient goldsmiths to build an entirely new system of gold banking.

What is more important, the new system can be grounded in the law of bailments rather than Carr v. Carr, 1 Mer. 543 (1811), and subsequent English cases holding that a bank deposit is a loan to the bank. For a discussion of these cases, which established the legal basis for fractional reserve banking, see M. Rothbard, The Mystery of Banking (Richardson & Snyder, 1983), pp. 93-95 & notes.

Just as war is too important to be left exclusively to generals, banking with real money is too important to be left entirely to bankers. The Constitution does neither. All participants in the gold mining industry — managements and investors, analysts and miners — should prepare to seize what could be an historic opportunity to move public policy in the constitutional direction of greater economic freedom and the right of all people everywhere to the use and benefits of specie.

June 1, 2002. Money in Court: Paving the Road to Ruin

[Note: Presentation on Thursday, May 23, 2002, to a seminar at the Grocers Hall, London, organized by the Association of Mining Analysts and sponsored by Durban Roodepoort Deep on Prospects for Gold – A new era or more toil ahead?]

As indicated on the program, your chairman, Michael Coulson, has asked me to address: “The gold anti-trust action – the Boston court judgement and the road ahead.” While I will speak to the assigned topic, my own title for this talk is Money in Court: Paving the Road to Ruin, and I will speak from the perspective of the American Constitution.

Gladstone described it as “the most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man.” W.E. Gladstone, “Kin Beyond Sea,” The North American Review (September-October 1878), p. 185. The Constitution grants to Congress exclusive power “To coin Money [and] regulate the Value thereof.” The states are expressly forbidden to “coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; [or] make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts.” These provisions have never been changed or amended.

Until the Civil War, no one would have disputed this statement by Daniel Webster in a speech to the Senate on the Specie Circular in 1836:

[T]here can be no legal tender in this country, under the authority of this government or any other, but gold and silver. … [This is] a constitutional principle, perfectly plain and of the highest importance. … To overthrow it would shake the whole system.

The financial demands of the Civil War brought about the federal government’s first experiment with a paper legal tender, the so-called “greenbacks.” The issue of their constitutionality did not reach the Supreme Court until after the war ended. In 1869, in the case of Hepburn v. Griswold, 75 U.S. (8 Wall.) 603, a closely divided Court held that the greenbacks were unconstitutional. A year later, following a change in the composition of the Court, this ruling was reversed in the Legal Tender Cases, 79 U.S. (12 Wall.) 457, by a 5 to 4 vote. The majority opinion stated (at 553):

The legal tender acts do not attempt to make paper a standard of value. We do not rest their validity upon the assertion that their emission is coinage, or any regulation of the value of money; nor do we assert that Congress may make anything which has no value money. What we do assert is, the Congress has the power to enact that the government’s promises to pay money shall be, for the time being, equivalent in value to the representative of value determined by the coinage acts … .

Fourteen years passed before the legal tender issue again came before the high Court. In the 1884 case of Juilliard v. Greenman, 110 U.S. 421, the question was whether Congress could make paper a legal tender in time of peace as well as war. With the cooling of Civil War passions and the effective reinstatement of the gold standard, many expected that the ruling in the Legal Tender Cases would be curtailed if not reversed, and that the monetary principles of the Constitution would be reasserted. When the decision in Juilliard disappointed these hopes, it provoked considerable popular criticism.. The New York Times wrote (as quoted in C. Warren, The Supreme Court in United States History (Little Brown, 1924), vol. 3, pp. 378):

[It is a decision] which, while it must command obedience, cannot command respect, a decision weak in itself and supported by reasoning of the most defective character, inconsistent with the previous decisions of the Court on like issues, and singularly, almost ridiculously, inconsistent with the traditional interpretation of the Constitution, with the spirit of that instrument and its language.

Although the Legal Tender Cases and Juilliard had little real effect on the monetary system of the era, they set unfortunate precedents that were later used to support the monetary measures of the New Deal. The greenbacks also caused widespread use of gold clauses in bonds and other debt instruments, which regularly provided for payment “in United States gold coin of the present standard of value [then $20.67 per ounce].”

In 1933, Franklin Roosevelt nationalized the U.S. gold supply and began the process of devaluing the dollar from $20.67 per ounce. Under the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, Congress set a new value for the dollar at $35 per ounce and invalidated all existing obligations to pay in gold at the former parity. The constitutionality of this measure was addressed by the Court in 1935 in the Gold Clause Cases, 294 U.S. 240.

One of these cases, Perry v. United States, 294 U.S. 300, involved the gold clauses in government bonds, which presented a special problem because the government was altering the terms of its own obligations. In a 5 to 4 decision, the Court held that Congress could, pursuant to its power to regulate the value of money, invalidate gold clauses in private contracts but not in government bonds. As the Court explained in Perry (at 350-351):

There is a clear distinction between the power of the Congress to interdict the contracts of private parties … and the power of the Congress to alter or repudiate the substance of its own engagements … . By virtue of the power to borrow money “on the credit of the United States” [emphasis in original], the Congress is authorized to pledge that credit as an assurance of payment as stipulated, — as the highest assurance the Government can give, its plighted faith. To say that the Congress may withdraw or ignore that pledge, is to assume that the Constitution contemplates a vain promise, a pledge having no other sanction than the pleasure and convenience of the pledgor. This Court has given no sanction to such a conception of the obligations of our Government.

But recognizing the general decline in prices during the Depression era, the Court continued:

Plaintiff [Mr. Perry] has not shown, or attempted to show, that in relation to buying power he has sustained any loss whatever. … On the contrary, payment to the plaintiff of the amount which he demands [i.e., $35 for each $20.67 previously owed] would appear to constitute not a recoupment of loss in any proper sense but an unjustified enrichment.

So, at the end of the day, the “unjustified enrichment” or windfall profits arising from the devaluation did not go to Mr. Perry and other holders of the government’s gold bonds, but to a new Exchange Stabilization Fund in the U.S. Treasury.

After World War II, although American citizens still could not own gold, the gold parity of the dollar remained set at $35 per ounce under the Bretton Woods Agreements, and foreign central banks were able to convert dollars at this rate until President Nixon closed the gold window in 1971. The constitutionality of this measure, which also violated the treaty obligations of the United States, has never been addressed by the Supreme Court. More generally, the Court has expressly refused on several occasions since 1971 to consider the constitutionality of the post-Bretton Woods system of unlimited paper money having no defined value.

Since 1974, Congress has made gold ownership by Americans legal again, re-authorized the use of gold clauses in private contracts, and provided that gold should trade in a free market like other commodities. In 1978 Congress also approved the Second Amendment to the Articles of the International Monetary Fund under which member nations agree (Art. IV, s. 12(a)) to: “the objective of avoiding the management of the price, or the establishment of a fixed price, in the gold market.” This amendment also bars members from linking their currencies to gold.

Now, with the legal and constitutional stage set, let me turn to the gold anti-trust action. The complaint was filed in December 2000 in the federal district court for Massachusetts. I was the plaintiff, asserting claims both as a private shareholder in the Bank for International Settlements and as a holder of gold preferred shares of Freeport McMoran Copper & Gold. The defendants included the BIS, certain U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve officials, and several large, well-connected international banks active in gold trading.

The complaint was posted on the Internet and received wide circulation, including many repostings at different sites. Accordingly, I have no idea how many times it was downloaded. What I do know is that when the German translation of the complaint was posted a year later, 1000 copies were downloaded within the first two weeks. Also, over 20,000 copies of GATA’s Gold Derivative Banking Crisis (www.gata.org/test.html), in many ways a precursor document to the complaint, were downloaded from the GATA website prior to the filing of the complaint.

Although factually complex and procedurally complicated, the case at heart asserted two straightforward propositions that flow logically from gold’s current legal and constitutional status as a commodity rather than money.

Proposition One. The power to set gold prices rests exclusively with Congress. Because Congress has mandated that gold trade in a free market rather than serve as legal money and the constitutional standard of value, statutes passed during the gold standard era authorizing the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve to deal in gold cannot now be read to permit them to intervene in the gold market for the purpose and with the intent of affecting gold prices.

Proposition Two. As an ordinary commodity trading in a free market, gold is covered by the Sherman Act’s prohibition on price fixing. Under U.S. antitrust law, price fixing is per se illegal, meaning that it cannot be justified by any sort of rule of reason analysis, and it is frequently prosecuted as a criminal offense.

Factually, the case revolved around two intertwined events: the freeze-out by the BIS of its private shareholders and price fixing in the gold market, allegedly orchestrated through the BIS by officials from the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve, and carried out through the defendant bullion banks. The scenario might loosely be described as a 1990’s reprise of the London gold pool, cobbled together in the 1960’s in a futile effort to save the Bretton Woods system.

With respect to the price fixing allegations, the complaint included a bunch of statistics and information from official and corporate reports. It also relied on the words of participating officials themselves. In 1998, Alan Greenspan testified to Congress that “central banks stand ready to lease gold in increasing quantities should the price rise.” In late 1999, after the price of gold rallied sharply in response to the Washington Agreement, Edward George, Governor of the Bank of England, was reliably reported to have confided to a mining company executive:

We looked into the abyss if the gold price rose further. A further rise would have taken down one or several trading houses, which might have taken down all the rest in their wake. Therefore, at any cost, the central banks had to quell the gold price, manage it. It was very difficult to get the gold price under control but we have now succeeded. The U.S. Fed was very active in getting the gold price down. So was the U.K.

The complaint alleged that the motives for the price fixing were to thwart gold’s function as an indicator of U.S. inflation and the health of the dollar, as well as to rescue the bullion banks from risky short positions in physical bullion — positions built up through gold leasing from the central banks and apparently confirmed by Mr. George’s statement on the consequences of the Washington Agreement.

After the complaint was filed, the GATA army went to work searching for additional evidence. Last summer, in the course of following up one of their leads, I came across former treasury secretary Lawrence Summers’ 1988 essay on “Gibson’s Paradox and the Gold Standard,” which sheds further light on the motives for the price fixing scheme.

Lord Keynes gave the name “Gibson’s Paradox” to the observed correlation under the gold standard between long term interest rates and the price level. Restated for today’s world, Gibson’s Paradox holds that real long term interest rates should move inversely to gold prices, and that is what then Professor Summers demonstrated, at least to his own satisfaction, for the period from 1971 to 1985. At my request, Nick Laird at www.sharelynx.net prepared this chart:

As you can see, the relationship described by Gibson’s Paradox held true from 1977 to 1995, but then began a period of severe breakdown. According to Professor Summers, all prior breakdowns over the two centuries covered by his research were attributable to what he called “government pegging operations,” such as occurred at the end of the Bretton Woods period. It is not my purpose here to engage in an extended discussion of Gibson’s Paradox. For more on this subject, including a link to Mr. Summers’ original essay, see Gibson’s Paradox Revisited: Professor Summers Analyzes Gold Prices.

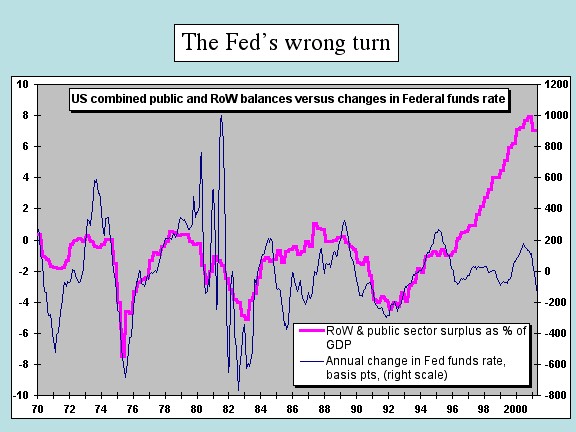

However, I cannot pass from Gibson’s Paradox without noting one further point. In today’s first presentation, Peter Warburton of Economic Perspectives put up a chart to show what he called “The Fed’s wrong turn” (copy of chart below courtesy of Dr. Warburton, author of the highly regarded Debt & Delusion (Penguin Books, 1999) and former chief economist at Robert Fleming). As you can see, the wrong turn took place in 1995, a date that is associated not only with the breakdown in Gibson’s Paradox, but also with several other key events relating to the gold price fixing scheme.

[Note: “RoW” denotes “Rest of World,” so that its net acquisition of financial assets (“NAFA”) equates to the balance of payments on current account with the opposite sign. The complete flow of funds equation is Private Sector NAFA + Public Sector NAFA + RoW NAFA = 0. Thus, when as in 2000 the public sector and rest of world are both in strong surplus, the private sector counterpart is in heavy deficit, and thus a net borrower of funds from the financial system. As described by Dr. Warburton: “The Fed’s wrong turn was the implicit or explicit decision to ignore an escalation of the public and RoW surplus (= combined private sector deficit) and not to raise interest rates/tighten credit conditions. Basically, it was the Fed’s responsibility to reactivate the private sector saving reflex to help finance the corporate deficit and to restrain the corporate sector from taking on too much debt.”]

In November 2001, after extensive briefing, the case was heard on the defendants’ motions to dismiss. This is a procedure under which defendants argue that even if all the facts alleged in the complaint are taken as true, the plaintiff for one legal reason or another is not entitled to any relief from the court.

On March 26, two months ago, the district judge issued a lengthy published opinion (copy available at www.zealllc.com/files/Dismissal.pdf) in which he stated the facts in some detail, including the Greenspan and Eddie George quotes, but dismissed the case on two legal grounds: first, that I lacked “antitrust standing” to bring the price fixing claims; and second, that the Treasury and Federal Reserve officials had qualified immunity from my claims based on their lack of legal or constitutional authority to manipulate gold prices.

A plaintiff in a price fixing case must not only meet the statutory requirement of injury to his business or property caused by the price fixing, but also a judicially imposed requirement that his injury be sufficiently direct, making him an “appropriate” plaintiff. Thus common shareholders in a company ordinarily lack standing to complain of price fixing in the company’s markets. The company itself is deemed a more appropriate plaintiff because it has suffered direct injury. Any injury to the shareholders is simply derivative of that to the company. On the other hand, where cash prices for copper were set by reference to prices for copper futures on the COMEX or LME, purchasers in the cash market were granted standing to sue for price fixing in the futures markets. Similarly, farmers selling soybeans in the cash market were given standing to complain of price fixing in soybean futures on the CBOT.

My Freeport gold preferred shares pay quarterly dividends equal to the cash value of a specific weight of gold based on the average London PM fix over a preceding five day period. They will be redeemed in 2006 for the cash value of one-tenth ounce of gold calculated in the same way. Because these payments are the exact equivalent of selling gold in the London market while New York is open, I argued my case should be governed by the copper and soybeans cases, not the common shareholder cases. Close, but no cigar. The judge conceded that I had a point, but ruled that a gold mining company would be a “more appropriate” plaintiff.

What may sound like an open invitation to a gold mining company to take up the cause is withdrawn by the judge’s decision on the immunity issue.

Here the judge ruled that the statutory provisions from the gold standard era granting Treasury and Federal Reserve officials authority to “deal in gold” were sufficiently elastic to give these officials reasonable grounds for believing, perhaps mistakenly, that they have authority to manipulate gold prices. In other words, the power to deal might include the power to deal from the bottom of the deck. Does it in this case? Do these officials in fact have statutory or constitutional authority to manipulate gold prices? The judge did not say. He just said they might reasonably have thought that they did.

Ordinarily questions of legal or constitutional authority are decided before the question of qualified immunity. Proceeding in this fashion, as the Supreme Court itself has noted (Wilson v. Layne, 526 U.S. 603, 609 (1999)), “promotes clarity in the legal standards for official conduct, to the benefit of both the officers and the general public.” That is, first decide whether the challenged conduct was illegal or constitutional. Then, if it was, decide whether the defendant officials are nevertheless entitled to qualified immunity because they had reasonable grounds for believing in good faith that were acting in a legal and constitutional manner even though they were not.

Accordingly, the person who brings the first case challenging specific illegal or unconstitutional conduct may lose, but by establishing its wrongfulness, he sets the necessary groundwork for future successful cases based on the same conduct. However, should a gold mining company bring a price fixing case like mine, it will lose to the same qualified immunity defense. It is a defense that cannot now be overcome except by a ruling in a prior case that Treasury and Federal Reserve officials lack authority to manipulate gold prices. Qualified immunity thus becomes absolute immunity when courts refuse to determine the legality of the underlying conduct as happened in my case.

Where does that leave us? What’s ahead? Three observations:

Power of the Internet. First, although the case was dismissed, the point was made. Even without pre-trial discovery under court procedures, the GATA army has produced ample evidence. It may never be presented in court, but much of it has been presented on the Internet. Facts speak for themselves. The allegations of the complaint are widely accepted because all the assembled evidence permits no other reasonable conclusion. We may never know all the details, but we do know to a virtual certainty that gold prices have been officially suppressed in a major way since sometime beginning around 1995. What’s more, they have been rising steadily since the judge’s March 26 decision, hardly a vote of no confidence in the truth of the basic allegations.

Power of Gold. Second, if gold were not permanent, natural money, I would have had antitrust standing just like the copper users and the soybean farmers did. What’s more, if gold were the barbarous monetary relic that many like to claim, the G-10 central bankers would not have been so interested in rigging the gold market. Nor would they have tried to have their cake and eat it too by leasing huge amounts of gold for sale into the market rather than selling it outright.

Power of the Constitution. Third, the American Constitution is neither a technical legal document nor simply a declaration of rights. It is a plan of government. But it is not self-executing. Its power rests on the fidelity of the governed to the plan and to the wisdom that it embodies. The proof of Gladstone’s statement lies in the results, which have been pretty good when the Constitution is followed, as happens most of the time, but not so good on the few occasions when it has been seriously violated.

The nation’s greatest constitutional convulsion — the battle over slavery — came in the one area where the plan could not be perfected at the time of its adoption due to irreconcilable sectional differences. More recently, the Vietnam experience demonstrated the folly of sending an army of half a million men, mostly draftees, to fight on the other side of the world without obtaining at least the practical equivalent of what the Constitution expressly requires: a declaration of war by Congress.

At its most fundamental level, the Constitution provides for three branches of government — legislative, executive, and judicial — not four. It does not confer a separate banking power — and certainly not the power to issue unlimited amounts of paper money — on an independent central bank, let alone one that is effectively exempt from any serious judicial review. Yet in the real world, that is what exists today.

The road ahead is the road we are on — a road paved by the courts and already taken too far. It is, and it has always been, the royal road to ruin: the well-worn path which, as the framers of the Constitution knew from both history and personal experience, is traveled by all who chose government paper over gold or silver as their standard of value.