January 18, 2001. Cycles of Manipulation: COMEX Option Expiration Days and BOE Auctions (Updated)

Here is another chart from Don Lindley that pretty much speaks for itself. COMEX gold options expire on the second Friday of each month. Major option cycles expire every other month, creating a sharp drop in total open interest as the current month expires and is replaced the following day with a new cycle. The new cycle, of course, begins with zero open interest. The expiring cycle terminates with cash settlement or conversion into futures as for delivery. Each new cycle will require physical gold to support delta hedging of the new puts and calls as they are written. Enter, conveniently, a British gold auction.

At my request, in the chart below Don has placed green triangles to indicate the date of each British auction. The yellow triangles indicate the date of the press release announcing details of the auction, usually a week or so in advance. Last Friday, January 12, marked the end of another major COMEX option cycle. Contrary to its prior practice, the Bank of England announced in its press release disclosing the results of its November auction that the January auction would take place on Tuesday, January 23. Perhaps it acted early out of concern that an incoming Bush administration might look with disfavor on continued criminal price fixing in the New York gold market. In that event, Katie bar the door, or should I say, close the vault.

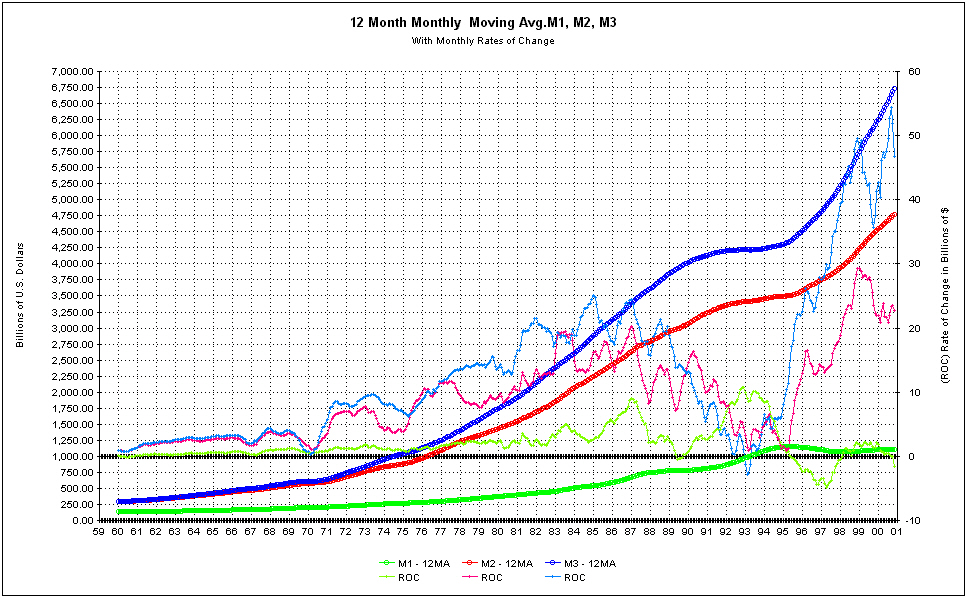

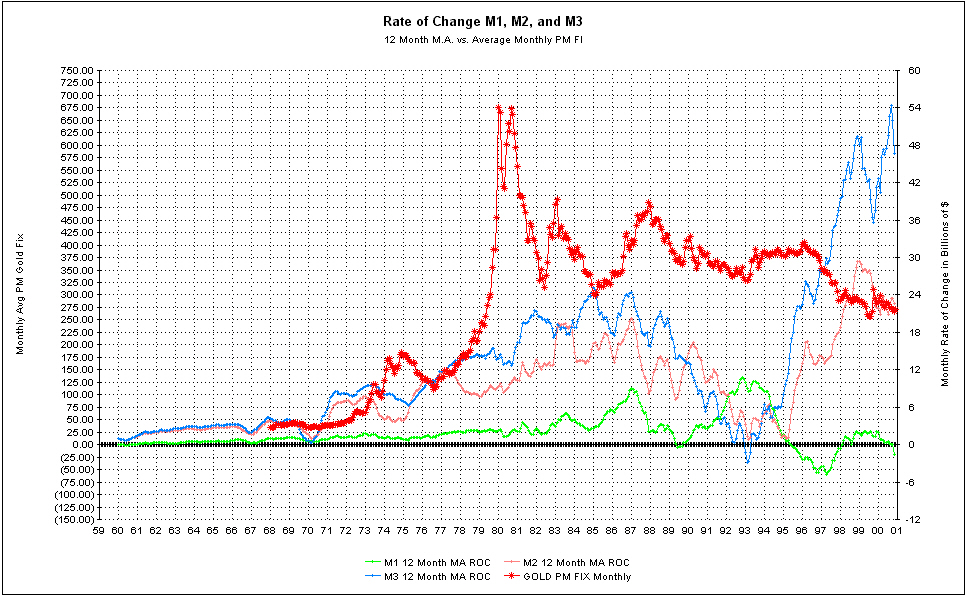

January 14, 2001. U.S. Money Growth: Words Unnecessary

Don Lindley sent me the following charts, which he has kindly allowed me to share with readers of The Golden Sextant. Some of you will know Don from his postings at Gold-Eagle regarding the Option Cube. Note also that Mike Bolser has just updated the GOLD MARKET REGRESSION CHARTS.

December 30, 2000. White House Adventure: Opening the Gold Closet

The second Bush’s first administration will enter the White House with more detailed knowledge of its physical layout and recent operating procedures than any new administration in modern U.S. history. But keeping skeletons hidden inside White House closets is getting tougher, thanks in large measure to the Internet. Once tightly shut to the outside world, the chamber of presidential extramarital affairs was forced open during the Clinton administration. What emerged was no less startling than Sir Thomas Beecham’s description of the harpsichord: “Two skeletons copulating on a corrugated tin roof.” If skeletons rattle for George W. and his new administration, they are likely to come from a different and even more secret White House chamber: the gold closet.

The nation’s policies on gold have been set at the White House since the arrival of the New Deal. They are closeted because they cannot withstand legal or constitutional scrutiny. But not until the Clinton administration did manipulation of the free market price of gold become national policy, all as set forth in the complaint in the gold price fixing case. The new President and three of his top cabinet officers — Attorney General-designate Ashcroft, Secretary of State-designate Powell, and Secretary of the Treasury-designate O’Neill — must determine how to respond to this complaint. Today, trying to hide it in the gold closet is more than a bet against the power of markets. It is a bet, too, against the power of the Internet.

The opening question for the Attorney General is whether the Department of Justice should represent some or all of the government defendants, as would ordinarily be expected. However, the Attorney General is also responsible for enforcement of the antitrust laws. Under normal circumstances, a price fixing scheme of the size and scope alleged in the complaint would not just attract the attention of the DOJ. It would be considered for criminal prosecution. As one current antitrust treatise notes (T.V. Vakeries, Antitrust Basics (Law Journal Press, 2000), p. 4-1): “Price fixing constitutes one of the most serious antitrust offenses. … Corporate executives involved in horizontal price fixing agreements face a substantial risk of criminal prosecution…. Justice Department policy is to seek fines against indicted corporations and prison sentences, as well as fines, against individual executives….”

Thus the Attorney General must resolve at the outset whether his obligation to enforce the antitrust laws disqualifies the DOJ from representing any of the alleged government participants, particularly in circumstances where the private corporate defendants may assert that their price fixing activities had official sanction or support. The Attorney General could find himself in a very awkward position should he try to defend officials of the Exchange Stabilization Fund or Federal Reserve while at the same time pursuing price fixing claims against the bullion banks. But to defend the entire gold price fixing scheme as legal would make a farce of the Sherman Act’s most fundamental prohibition. In short, unless there are well-founded grounds for denying the principal factual allegations of the complaint, the Attorney General has no easy option.

What is more, the Attorney General’s responsibilities are not confined to the antitrust laws. He is the nation’s chief law enforcement officer. The two Federal Reserve defendants are alleged to have exceeded the scope of their constitutional or legal authority not just by manipulating gold prices, but also by assuming seats on the board of the Bank for International Settlements, effectively making the United States a member of that organization. Its plan, apparently backed by the Federal Reserve, to shed the limitations imposed by partial private ownership of its shares and to become a public international financial institution akin to the IMF or World Bank raises serious constitutional issues regarding the conduct and control of U.S. foreign policy.

If the United States is to participate in an international organization which has broad economic power and influence, should it do so solely through the relatively independent Federal Reserve? Does the Constitution require that U.S. participation in any such organization be subject to direct presidential and congressional oversight? Indeed, even were it constitutionally permissible, is it advisable to confer on the Federal Reserve powers which may bring it into major conflict with the President or Congress on issues of foreign policy? If their appointments are confirmed by the Senate, how much authority on international economic or monetary affairs is General Powell or Mr. O’Neill prepared to share with the Fed chairman? More importantly, although the President decides conflicts among his cabinet officers, who resolves policy disputes between the secretaries of state and of the treasury on the one hand, and the Fed chairman and his colleagues at the BIS on the other?

An unlikely alliance of liberals and conservatives, ranging from Senator Jesse Helms (Rep., N.C.) to the Black Caucus, blocked congressional approval of proposed gold sales by the International Monetary Fund in 1999. Proceeds from the sales were marked for aid to heavily indebted poor countries, many in sub-Saharan Africa with significant export earnings from gold mining. These prospective beneficiaries themselves opposed the sales because the damage from probable lower gold prices threatened to outweigh any benefits from the IMF’s planned aid. What neither these nations nor apparently their U.S. congressional allies realized was that those pushing hardest for the sales wanted lower gold prices, and that if they could not achieve their objective by this means, they would try another, even if it meant going underground and employing the facilities of the BIS.

As a result, the foreign policy of the United States as regards sub-Saharan Africa in general, and South Africa in particular, has become intertwined with the U.S. relationship to the BIS, an issue that has never been considered by Congress. But these issues, important as they are, form only a small part of a much larger foreign policy mosaic, which in today’s global economy involves a number of difficult and complex issues relating to international trade and finance.

According to Gerald Seib of The Wall Street Journal (“Bush as Leader: Like Father, Yes, But Not Entirely,” December 13, 2000, p. A28): “In private conversation, [George W.] is far more interested in foreign affairs than his tentative public presentations suggest. … But Mr. Bush has also been candid in confiding to friends that he has much to learn in the foreign arena, particularly in international economics.” Good leaders know their own strengths and weaknesses, and seek to compensate for the latter by choosing competent advisers. Starting with his choice of running mate and continuing over the past couple of weeks, George W. looks to be assembling a strong team well-matched to his own abilities and instincts. He will need it. So will the country.

The Clinton administration is widely identified with positions favoring expanded trade, free markets, increased transparency, and a strong U.S. dollar. A major issue for the incoming Bush administration is whether that strong dollar — so vital to the U.S. economy — is largely a mirage reflecting covert manipulation of gold prices carried out over the past several years with the support of the ESF and the Fed. If the ESF has been intervening in the gold market as alleged in the complaint, the new President and his secretary of the treasury cannot avoid a decision on whether to continue these activities. From noon on January 20, 2001, they are the ESF.

In this connection, their worst fear should be not that the ESF has worked to hold down gold prices, but that these activities have constituted part of a broader pattern of market manipulations aimed at supporting stocks as well as the dollar. Since mid-1994, a number of analysts and market observers have noted unusually large purchases of S&P futures when stocks have fallen to critical levels. Like derivatives on gold, derivatives on equities provide not just enormous leverage but also an effective tool for potential market manipulators. The Clinton treasury department and the Fed have led the campaign for minimal regulation of derivatives, citing fears that this lucrative business dominated by a handful of large international banks might otherwise move offshore. The result, intentional or not, is that they have kept the tools for manipulating markets close at hand.

As George W. and his new administration determine how to respond to the gold price fixing complaint, they are confronted with a major policy dilemma. One path is to open the White House gold closet, to follow the Constitution and the laws of the land as best they can interpret them in good faith, and to make an honest and long overdue effort at real reform of the international monetary system. It is a hard path, likely when taken at this late date and through no fault of theirs to produce considerable economic dislocation and pain, but offering promise over the longer term for a better — even a golden — future.

The other path is the policy of the last three-quarters of a century: a war on gold, excessive monetary nationalism, and short run fixes at the expense of other nations. Perhaps this policy can succeed until the next election. But its continuation runs ever increasing risk that events may blow the doors clean off the White House gold closet under conditions of almost unimaginable crisis. Then, as the skeletons emerge pointing their long accusatory fingers at administrations that chose to trifle with the monetary provisions of the Constitution, history will rewrite reputations while pooh-bahs in finance ministries and central banks around the world relearn Sir Walter Scott’s familiar lines:

When first we practice to deceive.

Marmion,6.17(1808)

Among the more frequently asked questions about the gold price fixing case are why wasn’t it brought as a class action and what are the chances of getting to discovery. Many asking the first are past or present gold mining company shareholders interested in recouping some of their losses. Those asking the second typically express doubt as to whether these rich, powerful and politically well-connected defendants can truly be called to account in a court of law. In short, they anticipate that motions to dismiss will be granted even if in law they should not be.

Only the courts can answer the cynics. All I can say is that if we were to adopt their position without first making the best effort possible to vindicate the rule of law, we would never really know whether they were right or not. So my job is to pursue the litigation as best I can; GATA’s job is to raise funds for the effort and to publicize the cause.

The case was not brought as a class action for a number of reasons, some of which relate to certain technical and other requirements pertaining this form of lawsuit. In this connection, it cannot be disregarded that I am a pro se plaintiff. However, the rules governing civil litigation in the federal courts allow other parties to intervene, either as plaintiffs or defendants, if they have a right or interest that may be affected by the action. Plaintiff-intervenors are not generally permitted in antitrust cases brought by the government, but they are often allowed in private civil actions to enforce the antitrust laws. What is more, a plaintiff-intervenor may seek in an appropriate case to intervene as a class representative, and thus to convert the suit to a class action.

Plaintiff-intervenors in a price fixing case must ordinarily meet the same test for standing as an original plaintiff. Accordingly, for the reasons set forth in an earlier memo, shareholders in gold mining companies would face a distinctly uphill battle in seeking to intervene. But gold mining companies themselves have a much stronger basis for intervention, and shareholders should probably direct their efforts in this direction. Another obvious category of potential plaintiff-intervenors are other private shareholders in the Bank for International Settlements. Indeed, they probably have good grounds for intervention as of right. Other possible plaintiff-intervenors include persons who have dealt or traded in gold during the pendency of the alleged price fixing scheme, or those who are paid or compensated under formulas based on gold prices.

While intervenors normally come in as plaintiffs or defendants, they are not confined to the pleadings of the original parties. Rather, they are free to assert their own claims or defenses as they see fit. In the present case, for example, other BIS shareholders might well intervene but take a rather different approach from mine, such as downplaying or ignoring the gold price fixing and constitutional claims and focusing more narrowly on issues of share price valuation. On the other hand, someone who had traded gold futures or options would intervene only on the price fixing claims.

Potential plaintiff-intervenors also have the option of starting their own legal actions. When brought in federal courts, different actions in essentially the same matter are frequently consolidated under special provisions for complex and multi-district litigation. Many plaintiffs, especially in class action cases, adopt a quite proprietary attitude toward their lawsuits and resist intrusion by plaintiff-intervenors. My inclination, however, is to look more favorably on this possibility, particularly if a well-funded party with able counsel presents itself to the court.

Turning to the question of discovery, I am very pleased to report the formation of a Discovery Committee to assist me in determining precisely what information to request or search for and to help me evaluate what is received or uncovered. The committee consists of James Turk, Michael Bolser and Adam Hamilton, none of whom are strangers to readers of The Golden Sextant, members of Le Metropole Cafe, or the gold community in general. Bill Murphy, Chris Powell and I are most grateful to this knowledgeable and intrepid trio for their willingness to help. Their participation should give comfort to our friends and pause to our opponents.

December 8, 2000. Battle Stations!

Yesterday the proprietor filed his promised legal action: (1) to torpedo the attempt by the Bank for International Settlements to take the shares of its American issue — including his — at an unfairly low price by fraudulent means and without due process of law; (2) to fight the international gold price fixing conspiracy, which through its illegal activities has injured many around the world, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and other places with significant gold mining operations; and (3) to defend basic constitutional principles, including those relating to gold, money and banking. The complaint, filed in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, Boston, Massachusetts, is posted at a new site section: GOLD PRICE FIXING CASE.

I will have more to say about this legal action in future commentaries. In the meantime, my thanks to all who have supported the effort so far. But the battle has just begun. GATA and I are going to need all the support we can get: new allies, willing witnesses, as much relevant information as our many friends worldwide can provide or discover, and financial contributions.