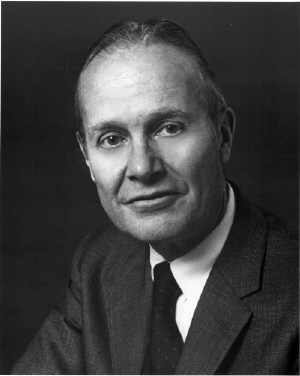

May 4, 1915 – November 7, 2006

Memorial Service, Hamilton Chapel, Belmont Hill School, April 26, 2007

Remarks of Reginald H. Howe

When Belmont Hill opened with 43 boys in the fall of 1923, Dad was eight — one of three students in the third grade, the school’s lowest. His father, founder and headmaster, led an original faculty of nine, including Dad’s mother, his sister Susan, just graduated from Windsor, and his future brother-in-law, Phil Wilson. Three years later, Dad’s uncle, Bill Barker, joined the faculty.

Sue and Phil were married in August 1925 under the old oak that used to stand between here and the Prenatt Music Center. That fall Finch Keller arrived from Rivers Open Air School. The boys joked that he came to Belmont Hill to get warm, but soon learned that the joke was on them as Finch’s teaching methods favored the stick over the carrot. The birth of the Wilsons’ first child, Anne, in 1927 lifted Dad, not quite 12, off the bottom rung of the family ladder, a seniority he enforced by insisting that all the Wilsons’ children address him as Uncle Dick.

The sudden death of Dad’s father in January 1932 changed the course of both Dad’s life and that of the school. We cannot know what would have happened absent this untimely loss. But we can fast-forward 25 years to January 1957 and a much happier event in the life of the school: the dedication of the George Wilbor Finch Keller Hockey Rink.

Dad, as chairman of the fund-raising drive for the rink, served as master of ceremonies. Finch, the honoree, would retire that June after 32 years on the faculty. Uncle Phil, the school’s first hockey coach and Exeter’s coach since leaving Belmont Hill in 1943, delivered the main address, followed by a dedication game in which Belmont Hill scored in the last minute to defeat Exeter 5-4.

This afternoon we are remembering Dad; tonight we will remember Finch. Among Dad’s many stories about Finch is one that Dad left out of his history of the first ten years of Belmont Hill. When, contrary to the private expectations of most of the faculty, Dad was admitted to Harvard, Finch went to Dad’s mother and told her that “Dickie” was not yet ready for Harvard and should take a PG year at Exeter. But Finch and the rest of the faculty were in for an even bigger shock. By the end of his junior year at Harvard, Dad was not just on the dean’s list, but in group II, placing him among the top 15% of his class academically.

To explain this astonishing development, we must look beyond Belmont Hill to the last capitol of the Confederacy, Danville, Virginia, which had sent one of its brightest and prettiest students to Wellesley College the same year that Dad went to Harvard. They met in January of their freshman year. A week later Dad invited his new girl to watch him play for the Harvard Freshmen hockey team, and afterwards to watch the Varsity game together until they would have to leave to get back to Wellesley by curfew.

But that night, rather than the normal practice of playing the Freshman game followed by the Varsity game, the Freshman and the Varsity played alternating periods, requiring five periods of hockey before the Freshmen game ended. Result: his southern belle missed curfew and was confined to campus for the next six weeks. Guilty and gallant, Dad trekked to Wellesley for the next six weekends to entertain the grounded rebel lass. The rest, as they say, is history, including a marriage that lasted more than 68 years.

In 1950, rather than moving with Lever Brothers to New York, Dad took a job with the Boston office of BBDO, a prominent advertising agency. When he retired 20 years later as office manager and a director of the firm, BBDO-Boston had become the largest ad agency in the city.

Several years later, entirely by chance, I overheard a conversation in an elevator at One Beacon Street among three young men from an agency in which Dad’s former creative director at BBDO had been a founding partner. They were returning from a breakfast meeting attended by top people from several agencies, and in talking about it, they dropped some names that I recognized, among them Jack Connors. As we approached my floor, one of them said: “You know, all those guys got their start at BBDO in the fifties or sixties; it must have been quite a place.” Indeed it was; those were the years Dad ran it.

The next time that I heard someone from the ad world talk about Dad’s career at BBDO was the night that he received the school’s distinguished alumni award. Jack Connors, the evening’s principal speaker and chairman of Hill Holliday, described his former mentor as “Mr. Integrity.”

Upon retiring from BBDO, Dad accepted an offer from Brad Washburn, the first director of the modern Museum of Science, to become its director of public relations and development. When Brad’s immediate successor unexpectedly departed after little more than a year on the job, Dad was appointed as the museum’s “interim” director while the search for a new permanent director got underway. Although the trustees soon dropped the “interim” from the title, Dad continued to use it because he thought the museum should not be changing directors too frequently.

When the search bogged down, the trustees asked Dad to continue as director until his planned full retirement at age 70 four years later. But Dad held firmly to the view that the Museum of Science should be headed by a trained scientist, and urged the search committee get back to work. Within a few months Dr. Roger Nichols, a professor at Harvard’s School of Public Health, was appointed as the museum’s next, and fourth, director. Carved in stone on a tablet in the museum’s lobby as its third director is Richard O. Howe, 1981-82.

Dr. Nichols asked Dad to stay on as deputy director until his retirement, and together they worked on two of the new director’s most important initiatives: one successful — the Mugar Omni Theater — ; and one not so — an attempt to create in Massachusetts a public high school for students gifted in math and science.

Before this project was vetoed by Governor Dukakis as being too “elitist,” it attracted key support from Chet Atkins, then chairman of the Senate Ways and Means Committee, and a great grandson of Belmont Hill’s most important early benefactor, about whom Charlie Jenney, a master here for over 50 years, wrote: “Dr. Howe’s admonition to new teachers was to conduct every class as though Mrs. Atkins might walk in at any minute, which the dear lady often did.”

Speaking at the dedication of the Howe building in the fall of 1957, an early graduate of the school opined: “Dr. Howe did not want a million dollar plant, but million dollar masters and boys.” Dad believed that the school needed all three, and truth be told, his father was far from indifferent to the school’s plant. One of the joys of Dad’s later years was watching the school prosper and grow under its current head, whom Dad often described as, and I quote, “… by far the best headmaster they’ve had up there since Dad.”

Dad grew up during the age of jazz and courted my mother in the big band era. All his life he loved listening to jazz, never more than when played by his nephew, Phil Wilson, Jr., who was a student at the New England Conservatory of Music when he came out to Belmont for the dedication of the Keller Rink. In 1965, after stints on tour with the Dorsey Brothers and playing with Woody Herman in New York, Phil joined the faculty of the Berklee College of Music, where he is Professor of Brass – a title that would fit him even if he couldn’t play a note on his horn. During his first year on the faculty, Phil formed what is today Berklee’s Rainbow Band. Still under his leadership, the band anchored a star-studded concert last Saturday evening to kick off Boston Jazz Week.

Long before Dad’s first angiogram some 30 years ago showed that he should already be dead, Dad managed to extract from Phil a promise to play at this service, whenever it might occur. Dad could not have known that Phil would bring with him one of his most talented students, but that he has done so makes my cousin’s tribute to his Uncle Dick a musical illustration of what our grandfather meant by million dollar teachers and boys.

Two years before his death, in an article for the Harvard Alumni Bulletin, Dr. Howe wrote that in his opinion schools and colleges could not do their job by adopting any single system of education, but only, as he put it, “by associating youth with such men of my own generation and Alma Mater as the Shalers, the Wendells, the Hurlbutts, and the Briggses, between whom and their students existed mutual friendless, trust, and respect, and a deep belief in each other’s sound citizenship, and willingness to accept responsibility in all human relations.”

For the Shalers et al., some here may substitute the Wilsons, the Kellers, or the Jenneys. Family, neighbors and friends, especially those from the advertising or museum worlds, maybe even some of his former peewee hockey players, may think of Dad, for teaching does not take place only in schools.

Great teachers have the good fortune to live on through their most rewarding joy: the success of their students, who in their turn may become teachers, renewing the cycle.

So enjoy the music, and all of you, whether you are staying for the Keller dinner this evening or not, please join us after the service at a reception in the Prenatt Music Center, where those going to the dinner will also receive their name tags and table assignments.