By a letter dated August 11, 2020, to the Belmont Hill Community under the heading “Per Aspera ad Astra” (through adversity to the stars), Jon Biotti, President of the Board of Trustees, and Greg Schneider, Head of School, announced the removal of the Belmont Hill bell from the campus:*

The Removal of the Bell: As many are aware, there are two historical bells located on the Belmont Hill campus. The first and best known is the bell in front of the Hamilton Chapel, which was the original bell on top of the chapel steeple in Connecticut before the building was moved to Belmont Hill in 1960. The second bell is located near the entrance to the MacPherson room. This bell was gifted to the School from a family that was a financial supporter in the early days of Belmont Hill. We have decided to take this bell down after sufficiently studying its history and its direct ties to slavery in Cuba on a sugar plantation. Our original plan was to keep it in place as a reminder and stern lesson about our history as intertwined with many facets of our country’s history. After listening carefully to our current and former students in our Town Hall meetings, our opinion changed. We have to take the bell down—the lessons from our history are eclipsed by the need to make our environment more comfortable and inclusive for all of our students. This decision was supported with a unanimous vote of our Board. [italics mine]

Unfortunately the Latin education of Messrs. Biotti and Schneider seems to have omitted Cicero, who observed: “Gratitude is not only the greatest of virtues, but the parent of all others.” Nobody even remotely familiar with the School’s history could take the first italicized sentence above as anything but a reference to Mrs. Atkins and her family. That Mr. Pullum, an executive in E. Atkins & Company, donated what seems to have been the replacement for the first bell sent by Mrs. Atkins and lost at sea does not excuse or justify that sentence. The gift of that bell, welcome as it was, scarcely elevated the Pullum “family” to a significant “financial supporter” in the School’s formative years.

In any event, the bell has long been associated with Mrs. Atkins, her family and Soledad plantation. In a very real sense, it was the only physical reminder on the School’s campus of her unique and critical role in its founding. Even today, in its new location at Robbins House in Concord, the bell remains associated with the Atkins family, but with a sterilized history largely cleansed of reference to its nearly full century of service at Belmont Hill, and with no mention of the extraordinary lady but for whom the School would not exist and who did so much to improve the lives of the workers at Soledad.

In the second italicized clause, “our history” can only refer to the School’s history in contradistinction to “our country’s history” separately referred to immediately thereafter. So what is the “stern lesson” about the School’s history? The clear implication is that the School was in part founded on money tainted by Cuban slavery, suggesting that Belmont Hill is in a similar position to several older educational institutions that have been forced to confront early histories of financial support from slaveholders, some of whom had reputations as rather abusive masters.

However, the history of Soledad plantation under management by the Atkins family paints a very different picture. E. Atkins & Company acquired Soledad by foreclosure in 1884, its first entry into the actual production of sugar in Cuba. Previously it had engaged in the transport of Cuban sugar to Boston, including financing some of the growers. It was their debts, run up during the Ten Years’ War, that led to the foreclosure. By 1886, when slavery was formally abolished in Cuba, not only were many plantations on (or past) the brink of failure, but also slavery for the most part had already died out, as it had at Soledad by the time of the foreclosure.

In 1875 the troublesome Cuban end of the family business was turned over to Edwin F. Atkins by his father, whose other business interests demanded more of his time. Thus the young Atkins and his bride, shortly after their marriage in 1882, found themselves—as proprietors of Soledad—deeply engaged in the post-slavery reconstruction of the Cuban sugar industry and the rejuvenation of Cuban society. Twenty years later Mr. Atkins could write to his wife (letter dated March 23, 1902, SixtyYears in Cuba, pp. 329-330):

Last night our apothecary was married. Of course I went to the wedding, and afterwards they had a dance. All of our people were there, and a very nice nice-looking set they were — Americans, English, German, Spanish, and Cubans, mostly of the latter class. Most of the girls were from town and some of them very pretty. One couple came to me and said, ‘Don Eduardo, you came to our wedding last year. We want to show you our baby. We will put it in your school by and by.’ There are lots of families here now and all seem happy and contented. Several of the men said last night there was no other estate where the employees were allowed to live with their families, or where the owners did anything for their comfort; that everywhere they were left to shift for themselves soon as the crop was in. It gives me a great sense of responsibility to feel so many people are dependent upon the success of this place.

All the girls on the place are picked up by some of the men as soon as they are of marriageable age, and then they settle down as fixtures. I don’t see how I can ever discharge any of them, as all the families are intermarried. You ought to see the crop of kids we are raising and educating, both in school and in the shops. Their parents call them my ‘flock’ and they come along faster than the colts.

An informative short history of the Cuban operations of the Atkins family can be found in “The Harvard Garden in Cuba – A Brief History”. Two points are particularly noteworthy. First, Mr. Atkins founded the Harvard Botanical Station in Cuba with “…the idea of improving the sugar cane and making new varieties through cross-breeding.” His principal partners in this endeavor were Dr. George L. Goodale and Professor Oakes Ames, both of Harvard University. After her husband’s death in 1926, Mrs. Atkins continued the family’s financial support of what under varying official names was often referred to as simply the Atkins Garden.

Second, and more relevant for present purposes, is the existence not 30 miles from the School of what can fairly be regarded as a companion bell to the Belmont Hill bell. Brought back to Massachusetts from Cuba by none other than Professor Ames himself, that bell hangs above his former home at Borderland State Park. A sidebar to the main article states in part:

Oakes Ames was a sensitive man with the mind of a scholar and the soul of a poet. He was deeply disturbed “by holding in bondage one’s fellow man and driving him to and from work by the note of the doleful bell, a kettle drum aided by the stinging of the lash.” It was this bell that he brought back with him to hang over his house in North Easton, as if it were a symbol for him of the liberation of the slaves of Cuba.

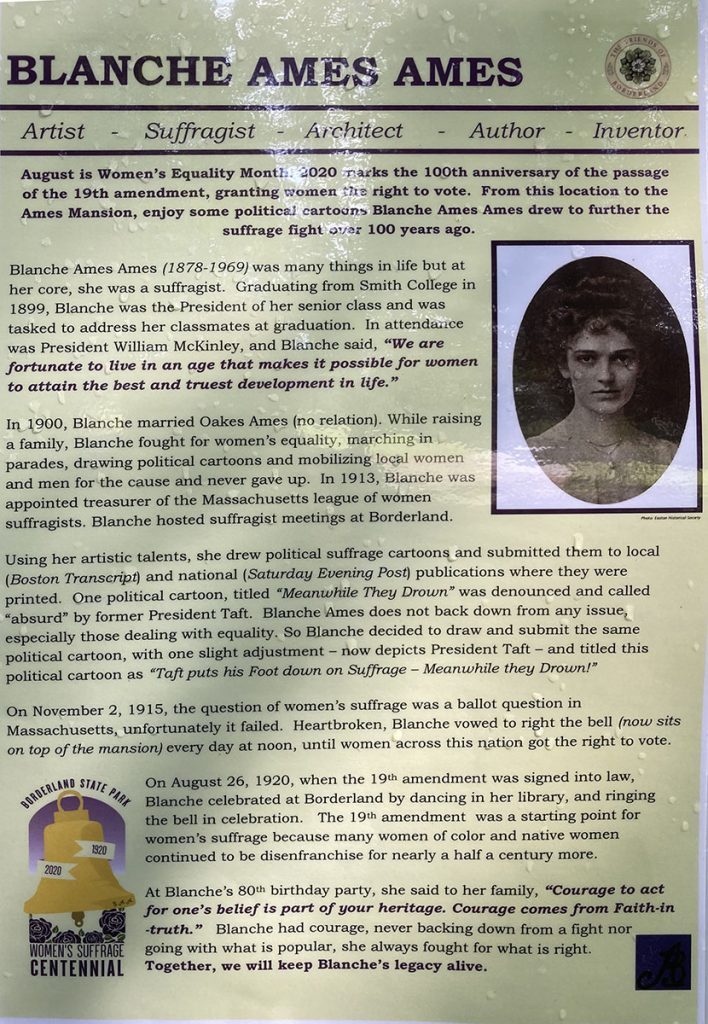

But where the Belmont Hill bell was repurposed to calling students to their lessons, the Borderland bell rang again and most vigorously in support of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote. Put to this service by Blanche Ames, the professor’s wife and an early suffragette, this bell highlighted the state’s celebration of the centennial of the 19th amendment in 2020.

The third italicized clause of the August 2020 letter, after again citing the supposed lessons from the School’s history, refers to the need to make the School “…more comfortable and inclusive for all our students.” Life is not always comfortable or inclusive. Students, if they are to function effectively in the real world, need to acquire sufficient mental toughness to operate in environments that are not merely uncomfortable but sometimes personally distressing or even offensive. Removal of the bell coddled an overly self-centered view of life unbecoming in tolerant and educated men.

Announcing removal of the bell in the manner that it did, the School joined a plethora of educational institutions that have tried to demonstrate their moral sense and commitment to DEI by renouncing any possible historical connections to slavery. But its act did nothing to improve the comfort of the people of Cuba or to increase their inclusion in the world economy, causes to which Mr. & Mrs. Atkins devoted much of their adult lives. In this regard, and uniquely for Belmont Hill students, a research project analyzing recent U.S. policies toward that poor and beleaguered nation might have proved a far more constructive, educational and mind-opening exercise than pursuit of what appears to be a largely faculty-driven obsession over the bell.

On her eightieth birthday Blanche Ames counseled her family: “Courage to act for one’s belief is part of your heritage. Courage comes from Faith-in-truth.” Belmont Hill students might be better instructed on character by the example of Blanche Ames ringing her slave bell for women’s rights than by the School removing its for their mental solace.

*Two days later I penned a response. Had I received the courtesy of a reply, it too would be posted. However, these men—who claim to be molding young men’s character—gave my letter to Bev Coughlin to deal with as best she could. Ultimately, two years later as I began publishing these articles, Bill Achtmeyer ‘73, longtime Vice-President of the Board, assumed responsibility for handling my previously ignored requests for information. Thankfully he has been reasonably accommodating.