Québec Libre: Gramme par Gramme

(la version française canadienne)

| CONTENTS | TABLE DES MATIÈRES |

|---|---|

| Introduction | Introduction |

| 1. U.S. Dollar Imperialism | 1. Impérialisme du Dollar É.U. |

| 2. Looney-Tooney Land | 2. Terre du Huard ($1) et du Polar ($2) |

| 3. Free Gold for Free Trade? | 3. Libre Échange à Prix d’Or? |

| 4. We the Politicians | 4. Nous les Politiciens |

| 5. Dumping Gold | 5. Abandon de l’Or |

| 6. Winter Survival | 6. Survivre à l’Hiver |

| 7. The Northern Confederacy | 7. La Confédération du Nord |

| 8. From Greenbacks to Snowflakes | 8. Des Billets Verts aux Flocons de Neige |

| 9. New Deal Light | 9. «New Deal» Léger |

| 10. Grams of Common Sense | 10. Le Bon Sens en Grammes |

| 11. Sword in the Shield | 11. L’Épée dans le Bouclier |

| 12. Québec Libre | 12. Québec Libre |

| 13. New Money, New Politics | 13. Nouvelle Monnaie, Nouvelles Politiques |

| 14. The Golden Square Mile | 14. Le Mille Carré en Or |

| 15. The Next Referendum | 15. Le Nouveau Référendum |

Delivering this year’s Godkin lectures at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, university president Lawrence H. Summers defended free trade and globalization while bemoaning that for too many both in and out of government: “Mercantilist economics is hard-wired into the brain.” See “Globalization Defended,” Harvard Magazine (July-August 2003), p. 75. Free trade rests on the principle of comparative advantage first enunciated by the classical economist David Ricardo, who assumed fixed exchange rates among currencies redeemable in specie at fixed prices, not politically managed floating exchange rates among unlimited paper currencies — a preference apparently hard-wired into the brains of most modern economists, including that of the former U.S. treasury secretary.

After World War II, the Bretton Woods agreements established a system of fixed exchange rates tied to the U.S. dollar, which was convertible into gold at $35/ounce upon request by foreign central banks. The system collapsed in 1971 due to the excessive buildup of dollars overseas arising from abuse of what General Charles de Gaulle called an “exorbitant privilege,” namely the ability of the United States to meet its balance of payments deficits regularly in its own currency, making them in the words of his monetary advisor, Jacques Rueff, “deficits without tears.”

To the cheers of most economists, the Bretton Woods system was replaced in 1973 by the present regime of floating exchange rates having no fixed relation to each other or to gold. Responding more to central bank interest rate policies, speculative capital flows, and official market interventions than to real trade balances and purchasing power parities, these floating — frequently gyrating — rates only complicate and disrupt free trade. But whether they can seriously impede or even survive globalization is another question altogether. Globally acceptable unlimited paper currencies are a very recent phenomenon; globally acceptable money — first silver and later gold — has existed for centuries.

The same technology that is responsible for globalization greatly facilitates the monetary use of gold, not only eliminating many of the practical inconveniences of old-fashioned gold coinage, but also making operation of a fully reserved system based on the law of bailments at least as economic as a fractional reserve system operated by banks on principles of credit. Computers and the Internet have created a world in which gold can serve directly as money without any assistance from governments or banks. Thus the gold standard, never the “barbarous relic” that Lord Keynes claimed, might yet be rendered a true relic by technological progress.

While this new world of gold money promises to look more like the nineteenth century heyday of the gold standard than the twentieth century’s monetary chaos, the transition will be wrenching, especially for governments that have made deficit finance and exchange rate management a way of life, or have allowed their official reserves to become overloaded with dollars and underweight in gold. Among the G-7 nations, Canada faces the stiffest challenges because in addition to scoring poorly on all these counts, it has failed to resolve fundamental constitutional discord over the proper place of Quebec, the second largest provincial gold producer, within the confederation.

1. U.S. Dollar Imperialism

[Impérialisme du Dollar U.S.]

What passes for an international monetary system today is largely nothing more than a dollar recycling program that leaves American consumers with more than their fair share of the world’s merchandise and foreign central banks with most of its excess dollars. Worse, the system appears incapable of rebalancing itself. As levels of U.S. debt and deficits continue to scale new heights, so do official foreign dollar holdings. These now approach $1 trillion, including almost $750 billion of U.S. treasury debt ($100 billion more than the U.S. Federal Reserve itself holds), and $200 billion of federal agency obligations. See “$1 trillion catch basin,” Grant’s Interest Rate Observer (June 20, 2003), p. 1.

Dollar balances generated by large trade surpluses with the United States reflect exports that are the driving force in the economies of many of its trading partners, making them reluctant to convert these balances into local currencies and risk choking off their own export-led prosperity with strengthening exchange rates. See Richard Duncan, The Dollar Crisis (John Wiley & Sons (Asia), 2003), esp. pp. 90-119. On the other hand, by holding excess dollar balances, foreign central banks effectively monetize U.S. government debt in much the same manner as the Federal Reserve itself. Left unrestrained, this process ultimately threatens to destroy the value of the dollar — and thus of foreign dollar reserves — through inflation.

As discussed in Gibson’s Paradox Revisited: Professor Summers Analyzes Gold Prices, two centuries of historical data demonstrate that in the absence of government interference, the value of gold moves inversely to real long-term interest rates. Under the gold standard, the value of gold was the reciprocal of the general price level since the gold price was fixed. In a free gold market, the value of gold is determined by its price. Accordingly, except as official intervention may for a time suppress free market forces, low nominal bond yields and low inflation as measured by the general price level should not be expected to coexist with low gold prices. Either real yields must rise through some combination of higher nominal rates and further disinflation or even deflation, or gold prices must rise.

On June 15, 2003, in his semi-annual economic report, Fed chairman Alan Greenspan assured Congress that the Federal Reserve “…stands ready to maintain a highly accommodative stance of policy for as long as it takes to achieve a return to satisfactory economic performance.” Responding to the inflationary implications of this statement in combination with record federal budget deficits for the foreseeable future, prices on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note and the defunct 30-year Treasury bond immediately fell, driving up their yields and setting off the sharpest decline in bonds in more than a decade. See, e.g., D. Chapman, “Bond Massacre!,” SafeHaven (July 30, 2003).

However, particularly in a world economic environment marked by sub-par growth, low short-term interest rates in the United States put pressure on its major trading partners as well as other trading nations to follow suit lest higher rates trigger unwanted appreciation of their own currencies. Indeed, even a nation with as long a tradition of sound money as Switzerland is not immune. See G.T. Sims, “Swiss Central Bank Leaves Itself With Limited Room to Maneuver,” The Wall Street Journal (August 11, 2003), p. A2.

In 2002, according to foreign trade statistics published by the U.S. Census Bureau, Canada’s exports to the United States amounted to almost US$210 billion versus imports of just over $160 billion, leaving Canada for the third successive year with a roughly $50 billion trade surplus from the world’s largest bilateral trading relationship. Therefore, maybe not quite as surprisingly as some have claimed, on the day of Mr. Greenspan’s congressional testimony, the Bank of Canada lowered its benchmark interest rate, causing the Canadian currency to drop sharply against its American counterpart. See, e.g., B. Little, “This central bank sure likes surprises,” The Globe and Mail (July 16, 2003).

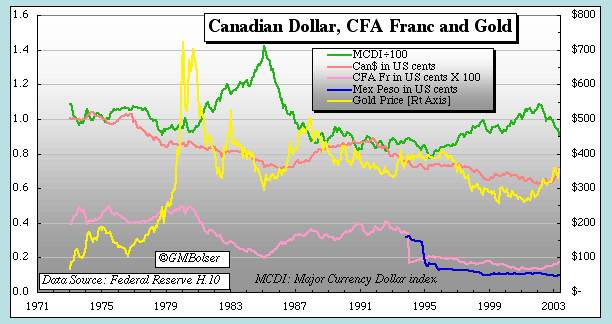

Having overdosed on the “strong dollar” of which Mr. Summers was a major architect, many nations — Canada prominently among them — are now addicted to exchange rates that reflect less than the full domestic purchasing power of their currencies. But “beggar-thy-neighbor” today promises “beggar-thyself” tomorrow as the U.S. dollar leads all paper currencies in a mad scramble to prove once more the truth of a statement regularly attributed to Voltaire: “Paper money eventually returns to its intrinsic value — zero.” (Note: Diligent search has so far failed to unearth a correct citation to the original statement, presumably in French.)

2. Looney-Tooney Land

[Terre du Huard ($1) et du Polar ($2)]

The Canadian and U.S. dollars both trace their ancestry to the same source: the Spanish milled dollar that circulated widely in North America prior to the American Revolution. However, the era of unlimited fiat money has witnessed a sharp divergence in American and Canadian tastes regarding the physical form of their respective dollars. Americans, who have never cottoned to two-dollar bills and resisted the Susan B. Anthony one-dollar coin, overwhelmingly prefer their one-dollar bills with George Washington’s portrait. Canadians, on the other hand, have embraced their one-dollar “looney” coin with sufficient enthusiasm to warrant a two-dollar coin, the “tooney,” and permit the retirement of all one and two-dollar bills.

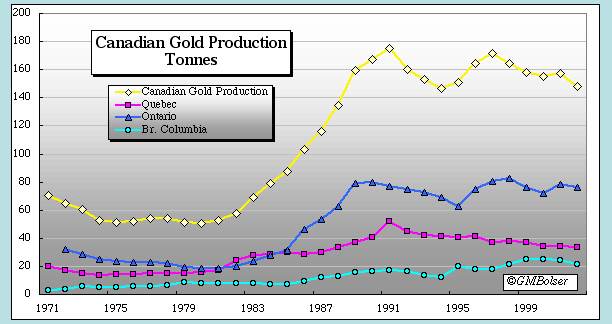

Gold mining played an important role in the economic development of Canada. See, e.g., A. Hoffman, Free Gold: The Story of Canadian Mining (McGraw-Hill, original ed. 1947, republished 1982). Today Canada ranks seventh among the world’s gold-producing nations, turning out roughly 150 metric tonnes of newly mined gold annually, most of which comes from the provinces of Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia as shown in the chart below, which has been prepared from data available from Statistics Canada, Ontario Mineral and Exploration Statistics, and Ministère Energie et Ressources du Québec. Production at Hemlo began in 1985.

Although no longer as important to Canada’s national economy as in former times, gold mining remains an important factor in the local economies of many rural communities, which have suffered measurably from lower gold prices caused by central bank gold sales. See M. Murenbeeld & Assoc., The Impact of Central Bank Gold Sales on the Canadian Gold Mining Industry (May 7, 2003); An Analysis of Central Bank Gold Sales and Its Impact on the Gold Mining Industry in Canada (May 2002). Surprisingly, however, rather than try to moderate the effect of central bank gold sales on gold prices, Canada has opted to sell much more of its gold sooner than any other country in the industrialized world.

Based on figures from the International Monetary Fund’s series on International Financial Statistics, the following table shows the official gold reserves of various nations at year-end 1985, 1993 and 2002. Canada sold 437 tonnes of gold from 1986 through 1993, reducing its gold reserves from 625 tonnes at the end of 1985 to less than 190 tonnes at the beginning of 1994, when it disposed of another 67 tonnes. Having sold an average of nearly 13 tonnes per year since, Canada is the world’s only major economic power to have virtually eliminated its gold reserves.

(millions of ounces except as otherwise noted)

| Country | end-1985 | end-1993 | end-2002 |

| Canada (ounces) | 20.11 | 6.05 | 0.60 |

| (tonnes) | 625 | 188 | 18.6 |

| Other G-7 | |||

| United States | 262.65 | 261.79 | 262.00 |

| France | 81.85 | 81.85 | 97.25* |

| Germany | 95.18 | 95.18 | 110.79* |

| Italy | 66.67 | 66.67 | 78.83* |

| Japan | 24.23 | 24.23 | 24.60 |

| United Kingdom | 19.03 | 18.45 | 10.09 |

| Other Euro Area | |||

| Austria | 21.14 | 18.60 | 10.21 |

| Belgium | 34.18 | 25.04 | 8.29 |

| Netherlands | 43.94 | 35.05 | 27.38 |

| Portugal | 20.23 | 16.06 | 19.03 |

| Switzerland | 83.28 | 83.28 | 61.62 |

| Other Developing | |||

| China (Mainland) | 12.70 | 12.70 | 16.10 |

| India | 9.40 | 11.46 | 11.50 |

| Russia | N/A | 10.20 | 13.60 |

| Other Gold-Producing | |||

| Australia | 7.93 | 7.90 | 2.56 |

| South Africa | 4.84 | 4.76 | 5.58 |

| All Countries** | |||

| (ounces) | 951.61 | 919.30 | 930.57 |

| (tonnes) | 29,599 | 28,594 | 28,945 |

*Increase represents difference between gold returned by the European Monetary Institute and gold transferred to the European Central Bank.

**Excludes gold held by the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements, and prior to 1998, the European Monetary Institute.

The table reveals a couple of subsidiary points also worth noting. First, the three “Other Euro Area” nations that have sold significant portions of gold reserves once as large or larger than Canada’s are no longer trying to maintain national currencies. Second, not only have China and Russia added modestly to their gold reserves, but there is some reason to believe that China may have additional unreported gold reserves. What is more, by adding 3.4 million ounces in 2001 after reporting 12.7 million ounces every year from 1981 through 2000, China may be signaling a positive view on the future role of gold in the international financial system. See, e.g., “Focus: China’s gold rush,” China Daily (September 25, 2003).

Diligent investigation last year by an interested Canadian citizen failed to draw from the Canadian government any explanation for the sale of its gold reserves. See E. Steer, “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling,” LeMetropoleCafe (November 13, 2002). Joe Clark’s short-lived minority government fell before it had an opportunity to carry out a plan announced in December 1979 to sell some gold to diversify Canada’s official reserves. This idea made some sense at the time, particularly as gold prices rallied to record highs in early 1980. However, diversifying foreign exchange reserves is one thing; eliminating all gold reserves is quite another.

Although the Bank of Canada commissioned a full report to justify its handling of foreign gold during World War II and obligingly provides figures on Canada’s gold sales since 1985, it directs all inquiries regarding the reasons for these sales to the federal government’s Department of Finance. Suffice it to say that here, despite months of effort that ended at the “risk management” office, Mr. Steer ran into the proverbial stone wall. However, he did extract an intriguing admission:

But in the dying seconds of that last phone conversation with the “risk management” department, the person I was speaking to dropped a bombshell! We had spoken twice before, and he was a real decent and honourable fellow. This is what I remember him saying; “Well Ed, you may not be happy with the answer you got, but I can tell you that your enquiries regarding what happened to Canada’s gold, set off alarm bells all over the Department of Finance. There are two things that this department is extremely sensitive about, and that is one of them.” If he hadn’t said that, this article would never have been written. [Emphasis supplied.]

Absent any official explanation, Mr. Steer offers his own fascinating theory to explain Canada’s gold sales and invites others to do the same. He suggests that at the 1985 “Shamrock Summit” in Quebec, Ronald Reagan obtained Brian Mulroney’s support for a plan to bankrupt the old Soviet Union by suppressing prices for oil and gold, its two major sources of hard currency. On this hypothesis, Canada’s gold sales were its unsung but important contribution to winning the Cold War, and they had the additional and not wholly incidental effect of burnishing the vain Mr. Mulroney’s image with his fellow world leaders.

Compared to the United States and other major western powers, Canada’s gold reserves in absolute size were rather modest. Assuming the existence of the plan suggested, and as Mr. Steer himself mused, it seems rather unlikely that Canada would have been asked or have agreed to shoulder almost the entire burden of gold sales by itself. Other internationally coordinated schemes to control gold prices, e.g., the London Gold Pool from 1961 to 1968, have not put most of the burden on a single country. What is more, by ultimately declining to support Mr. Reagan’s “Star Wars” defense initiative, the Mulroney government passed up what for Canada would have been a far cheaper as well as more effective means to squeeze the finances of the Soviet Union, which in any event had collapsed before Canada’s gold sales really shifted into high gear in 1992.

Countries do not unload large chunks of their gold reserves lightly. More often than not even gold sales ostensibly undertaken to diversify official reserves are in fact motivated by reasons touching more important national interests or even national survival. As prime minister from 1984 to 1993, Mr. Mulroney faced two problems that by historic standards might have warranted gold sales if they could have contributed to a solution: securing a comprehensive trade agreement with the United States and dealing with the constitutional challenge presented by the separatist movement in Quebec.

3. Free Gold for Free Trade?

[Libre Échange à Prix d’Or?]

Almost immediately upon taking office, Mr. Mulroney set about making good on his campaign promise to “refurbish” Canadian-U.S. relations, which had fallen into serious disrepair under his predecessor, Pierre Eliot Trudeau. See, e.g., K.R. Nossal, “The Mulroney Years: Transformation and Tumult,” Policy Options (June-July 2003). The new prime minister, in a reversal of his earlier policy stance against free trade, soon committed his government to the campaign that culminated in the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement (signed January 2, 1988; effective January 1,1989) and later the North American Free Trade Agreement (effective January 1, 1994).

The Canadian government appointed its chief trade negotiator in November 1985, and trade negotiations with the U.S. representative began in Ottawa the following May. But a year later, with the negotiations stalled and American support for an agreement waning, the outcome remained very much in doubt. Then, as Michael Hart recounts in A History of Canada-US Free Trade (1999 conference paper, part 8):

The pundits and pessimists in both countries, however, were proved wrong. The Canadian government stuck to its guns and determined that it had to have an agreement. Also surprisingly, both the US administration and the Congress demonstrated that they were prepared to come to terms with the hard issues and to look forward rather than backward. In a dramatic series of events during the fall of 1987, political leaders from both sides hammered out a satisfactory package that had until then eluded the professional negotiators.

The Iran/Contra affair broke publicly in the fall of 1986, precipitating a strong rally in gold prices which was met by sustained heavy selling of gold on the Commodity Exchange in New York as well as indications of intervention in the gold market by the U.S. Exchange Stabilization Fund. See Complaint, paragraphs 49, 63. The stock market crash in October 1987 gave a further push to gold prices and triggered more official selling.

The U.S. government is always sensitive to increases in gold prices of sufficient magnitude to reflect negatively on the U.S. dollar. From around US$300/oz. in January 1985, gold prices climbed to $500 in December 1987 before retreating to $360 by the fall of 1989 and closing that year just over $400. Particularly in light of the extraordinary events that accompanied the three-year move to $500, the significant Canadian gold sales that were initiated during this period must have come as good news to the Reagan administration.

Whether these or later sales had any connection, direct or indirect, to the Canadian government’s strong interest in securing a comprehensive trade agreement with the United States must on the current state of the evidence remain a matter of conjecture. However, what is not in doubt, even if not fully apparent until the mid-1990’s, is that on balance free trade with the United States has transformed the Canadian economy and substantially augmented the wealth of Canadians. Viewed in this light, if a quid pro quo for the free trade pact were the 125 tonnes of gold reserves sold in 1986 through 1989, many and probably most Canadians would consider it real money well spent.

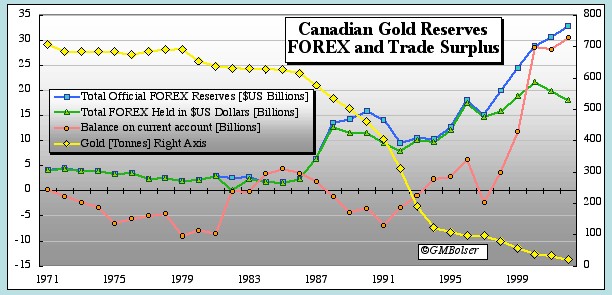

The following chart highlights the impressive growth of Canada’s current account surplus and foreign exchange reserves since 1989. It illustrates as well that while Canada’s gold sales up to that point were significant, they could also plausibly be justified solely on the grounds of diversifying official reserves. However, the chart also shows that as of the end of 1989, Canada’s gold sales had just begun a long descent that would rapidly accelerate from 1991 to 1995 before assuming a more gentle slope to near zero today. (Note: According to a press release from the Department of Finance, Canada’s gold reserves were about 175,000 ounces as of August 31, 2003.)

4. We the Politicians

[Nous les Politiciens]

If the documents that comprise the Canadian constitution were integrated into a single document in accordance with American constitutional tradition, it would be written in both official languages and the version in English would begin: “We the Peoples of Canada, in Order to form a more perfect Confederation … .” But today, were such a document prepared, true candor would compel that it open: “We the Politicians of Canada … .” What is more, were the original ratification procedures governing the American constitution applied, the Canadian constitution at least as revamped in 1982 would remain ineffective in Quebec until approved by vote of a convention called for the purpose or its equivalent.

Unlike the United States, Canada is a land of multiple peoples, including native peoples and its two founding peoples, the English speaking or anglophones (les anglos) centered in Upper Canada (Ontario) and the French speaking or francophone population which dominates Lower Canada (Quebec, originally New France). Quebec was transferred from French to British rule by the Treaty of Paris in 1763 following the complete subjugation of French forces after their crippling defeat on the Plains of Abraham outside the fortified city of Quebec in 1759.

In 1774, faced with trying to govern Quebec’s predominantly French and Catholic population at the same time that the American colonies were displaying decidedly rebellious tendencies, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act, which recognized the important role of the Catholic Church in the province and left French civil law in place. As a result, daily life in the former New France continued pretty much as it had before the conquest, and any immediate plans for trying to assimilate the population to British ways were shelved.

Quebec was thus launched onto the political trajectory that has made it both a unique province within Canada and a unique cultural and political entity within North America. For a comprehensive collection of materials in both official languages on the history of Quebec, see Quebec History (Internet Project, Marianopolis College, Montreal).

In most history books, the “Night of the Long Knives” is the phrase that Hitler borrowed from a popular German song to describe the purge carried out under his orders on the evening of June 30, 1934. In Quebec, La nuit des longs couteaux signifies the evening of November 4-5, 1981, when the premiers of seven English speaking provinces reached agreement with the Trudeau government on terms for “patriating” the Canadian constitution from Britain, but did so without informing Quebec premier and Parti Québécois leader René Lévesque, allegedly in violation of a prior agreement among all eight premiers — the Gang of Eight — to act on the matter only in concert.

Mr. Trudeau’s version of that evening is quite different, but whatever actually occurred, the event has poisoned Quebec’s relationship with the rest of Canada ever since. While Mr. Levesque may have made some errors or misjudgments in his dealings with the other premiers, Mr. Trudeau was no doubt emboldened by the results of the first Quebec referendum on sovereignty in 1980, when more than 60% of the electorate voted against a proposal for sovereignty within an economic association with Canada.

In the end, all Quebec’s legal challenges to patriation of the constitution without its assent were rebuffed. Accordingly, as patriated under the Canada Act, 1982 with the consent of nine provinces out of ten, the new constitution has the force of law throughout Canada. However, it lacks political legitimacy in Quebec, where it is widely perceived as having been imposed on the founding people who arrived first in “Kanata.” In trying to unite all Canada’s peoples under the new constitution, the politicians managed to deepen the divide between its founding peoples, to reopen old wounds going all the way back to the conquest, and to lay the groundwork for future constitutional disputes that would imperil the nation itself.

In brief summary, patriation retained the British North America Act (renamed the Constitution Act, 1867) to which Quebec had assented, while at the same time adding the Constitution Act, 1982. Its most important provisions included Canada’s first national Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which intentionally excluded any mention of property rights, and new and rather cumbersome procedures for amending the constitution through action in Canada and without recourse, even if only pro forma, to the British Parliament. See Constitution Acts 1867 to 1982 (English); Lois constitutionnelles de 1867 à 1982 (français).

Quebec’s principal objections to the new constitution centered on: (1) the omission of the right of veto over constitutional amendments that Quebec claimed to possess, and had as practical matter exercised, under the British North America Act; and (2) the failure to make sufficient provision for, or to give adequate recognition to, Quebec’s distinct culture, customs and language. In addition, since Quebec had adopted its own Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms in 1975, including some protection for property rights (ch. 1, s. 6), the new federal charter did not carry as much appeal as in other provinces and posed a potential threat to Quebec statutes, especially in the areas of language and education.

In the years since patriation, successive governments in Quebec have underscored the province’s objections to the new constitution by generally refusing to participate in the new amending procedures as well as by regularly invoking to the maximum extent permissible the so-called “notwithstanding clause” (s. 33 of the Constitution Act, 1982), which allows both the federal Parliament and the legislatures of the individual provinces to override certain provisions of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. See D. Johansen et als., The Notwithstanding Clause of the Charter (Parliamentary Research Branch, Library of Parliament, 1997).

In 1987, the Mulroney government tried to address Quebec’s constitutional concerns through the Meech Lake Accord, which proposed various amendments to the Constitution Act, 1982, to satisfy the five proposals for change that Quebec had affirmed would meet its objections, including the addition of a provision stating: “The Constitution of Canada shall be interpreted in a manner consistent with … the recognition that Quebec constitutes within Canada a distinct society.”

Opposed by Mr. Trudeau (as well as Jean Chrétien, the current prime minister, who assumed office in 1993), the Meech Lake Accord expired in 1990, having failed to obtain the required ratification by two provinces, Manitoba and Newfoundland, due in each case to the headstrong act of a single politician. A subsequent attempt to the same end in 1992, the Charlottetown Accord, was defeated in two separate referenda held simultaneously in Quebec and the other provinces. Almost 55% percent of the rest of Canada voted against a compromise “distinct society” status for Quebec that a similar percentage of its citizens voted was inadequate and unacceptable.

In the 1984 election, Mr. Mulroney’s Progressive Conservatives carried 211 of 282 ridings, including 58 in Quebec. With a smaller majority in 1988, the PC carried 63 ridings in Quebec. But as the Meech Lake Accord came apart in 1990, Lucien Bouchard split with the prime minister and led a group of Quebec deputies out of the PC to form the Bloc Québécois. In the west, many conservatives opted for the new Reform party, leaving the PC to disintegrate in the 1993 elections won by Mr. Chretién’s Liberals. As the regional party with the most seats, the Bloc became the official opposition with the charismatic Mr. Bouchard as its leader.

In Quebec, the separatist cause had suffered a setback in 1985 when the PQ lost to the Parti Libéral du Québec. But in 1994, promising to hold a referendum on full sovereignty, the PQ returned to power, and Canada accelerated toward constitutional crisis.

As the Monday, October 30, 1995, referendum approached, polls showed the Oui and Non votes in a dead heat. Emotions flared, especially in the old provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, as the two founding peoples teetered on the edge of divorce and the very existence of the nation hung in the balance. On the Friday preceding the vote, Canadians of all heritages and from every province flooded into Montreal’s Place du Canada and staged the largest political rally in Canadian history to show support for the Non side in a last minute effort to save their country. On a 93% turnout the following Monday, a bare majority (50.58%) voted Non to separation from Canada.

5. Dumping Gold

[Abandon de l’Or]

From the beginning of 1990 through 1995, the years of acute constitutional crisis beginning with the unraveling of the Meech Lake Accord and ending with the extremely close Quebec referendum, Canada sold 395 tonnes of gold, with the largest sales coming in 1991 (56 tonnes), 1992 (94 tonnes), 1993 (121 tonnes) and 1994 (67 tonnes). With a cost basis of $35/oz., the net gains on these sales were substantial.

Canada’s gold reserves are managed through the Exchange Fund Account. Its principal purpose is “to aid in the control and protection of the external value of the monetary unit of Canada.” Analogous to the Exchange Equalisation Account in Britain and the Exchange Stabilization Fund in the United States, Canada’s Exchange Fund operates with considerable secrecy and is exempt from the Financial Administration Act. However, its net income (or loss) each year, including capital gains, is paid (or charged) to the Consolidated Revenue Fund, which is the general pool of all income of the federal government.

Absent explanations from those responsible in both the Mulroney and Chrétien governments, the actual reasons for 1990-1995 gold sales cannot be known with certainty. However, the circumstances suggest two quite credible possibilites: (1) raising funds in excess of those available through, or outside the normal parliamentary or public scrutiny associated with, other budgetary channels for the specific purpose of financing activities intended to undermine support for separation; and (2) in the event of separation, depriving Quebec of a claim on significant gold reserves that might be used to help establish an independent Quebec monetary system.

Some have suggested that the proceeds of the gold sales were needed at the time to help offset large federal budget deficits; others that Ottawa was under pressure to sell “unproductive” assets. Neither suggestion is persuasive. If deficit reduction alone were the explanation, the government’s admitted high level of sensitivity and near total lack of candor are difficult to explain. Nor is selling gold like selling off a crown corporation. There are many valid reasons for privatizing state-owned enterprises quite apart from the capital gains that may accrue to the government (or operating losses that may be avoided).

Gold, like currencies, earns income when it is loaned to others. Gold in vault storage does not earn income precisely because its value does not depend on the promise of another. Rather, gold in safe storage is the most secure form of financial insurance available to both individuals and governments. Like any form of insurance, the level of desirable coverage in specific instances is a matter of judgment and reasonable people can disagree. But when a nation sells its gold reserves down to near zero, it is effectively canceling its financial insurance policy, not merely reducing its coverage.

At the end of 1995, Canada’s gold reserves were down to a mere 106 tonnes, making the Bank of Canada an all but impotent player in the scheme to suppress gold prices organized by the central banks circa 1995 and challenged in the Gold Price Fixing Case. Ironically, a speech delivered in London last February by the Governor of the Bank of Italy points to the G-7 meeting in Toronto in February 1995 as the likely birthplace of this long-sustained and covert attack on free market economics. See S. Corrigan, “Gold is boomeranging on George, Greenspan, and the other central bankers,” Capital Insight (August 27, 2003) and “It’s Dishonour, Sir,” Capital Insight (August 3, 2003).

An exception exists to the adage that there is no honor among thieves. Central bankers would rather steal from their fellow countrymen than lose face within their elite and powerful international fraternity. Thus, oblivious to or unconcerned about the damage that low gold prices were inflicting upon the Canadian gold mining industry, the Bank of Canada — presumably at the direction of the Department of Finance — continued after 1995 to make and announce picayune gold sales on a regular basis, and thereby to lend what support it could to the central banks’ scheme to suppress gold prices.

By the fall of 1999, Canada’s gold reserves had shrunk still further to not much over 60 tonnes. Not surprisingly, therefore, neither the Bank of Canada nor the Department of Finance were asked to participate in the Washington Agreement on Gold announced on September 26, 1999, under which the European Central Bank and 14 other European countries, including France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, agreed to limit their total aggregate gold sales to 2000 tonnes over the next five years. Nor did Canada volunteer to limit its future gold sales in accordance with the spirit of the agreement as did some other non-participants, including the United States and Japan. Instead, spurning a last chance to make just a small symbolic gesture of support for the Canadian gold mining industry, the federal government plowed ahead with its gold sales so that today less than 200,000 ounces remain.

With almost no gold reserves and being the only G-7 nation completely disassociated from the Washington Agreement, Canada is singularly ill-positioned either to negotiate concerning, or to participate in, any reforms of the international monetary system that elevate the importance of gold. The Bank of Canada and the Department of Finance are apparently betting that the signatories to the Washington Agreement did not really mean what they said in the opening sentence of that document: “Gold will remain an important element of global monetary reserves.”

6. Winter Survival

[Survivre à l’Hiver]

Canadians are used to dealing with winter, and many thrive on the sporting activities that snow and ice permit. But in a Kondratieff winter fun and games give way to a battle for sheer survival. In the economic cycle theory that takes it name from the Russian economist who first developed it, the function of winter is to flush accumulated and excessive debt from the economy so that it can enter a new springtime of genuine growth.

According to modern disciples of Kondratieff theory, the economic outlook for the next few years is grim indeed. See, e.g., interviews with Ian Gordon, editor of The Long Wave Analyst, at Financial Sense.com (July 27, 2002) and www.miningstocks.com (June 1999 and July 12, 2002). Whether events will unfold substantially as these analysts predict is unknowable, but they are indisputably correct on one point: there are incomprehensible amounts of debt that must be dealt with, especially in the American economy.

Richard Russell, a veteran market analyst old enough to remember the last Kondratieff winter a/k/a the Great Depression, thinks that the economic outlook for the United States is now so frightening that most people are simply unwilling to face it. As he puts it (“Escape and Fantasy,” Dow Theory Letters (July 29, 2003):

So what are people escaping from? I believe that consciously or unconsciously, they’re escaping from our future. And what is our future? I’ll say it once more — our future is “INFLATE OR DIE.”

What – you don’t understand what that means? Then I’ll rephrase it. Our future is “INFLATE OR REPUDIATE.”

* * * * *

We have a $10 trillion economy. How on earth is a $10 trillion economy going to service what’s coming up in the way of $38 trillion in debt [including unfunded liabilities]?

There are two choices. Repudiate a good chunk of this debt or at least cut it back drastically. Or finance the debt via the printing presses. Which one do you think the US government is going to choose? Look, if we’re running the printing presses full speed now, and the BIG expenses haven’t even hit yet, what do you think our leaders are going to do when the “debt hits the fan?” You guessed it, they’re going to inflate at a level that has never been seen before.

[See also, R. Russell, “On the Markets and Gold,” Dow Theory Letters (September 1, 2003).]

The famous free market economist Ludwig von Mises made essentially the same point in Human Action (Foundation for Economic Education, 4th ed., 1996), p. 572:

The wavelike movement affecting the economic system, the recurrence of periods of boom which are followed by periods of depression, is the unavoidable outcome of the attempts, repeated again and again, to lower the gross market rate of interest by means of credit expansion. There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.

As a result of free trade, the Canadian economy is more leveraged than ever to that of the United States. How well prepared is Canada for a severe global economic winter, whether it arrives in a blizzard of inflation, a cold blast of default and deflation, or both together? It used to be said that if the United States caught an economic cold, Canada caught pneumonia. What happens to the Canadian economy today if the United States catches economic pneumonia? What happens to the Canadian dollar if the U.S. dollar loses its status as the world’s principal reserve currency? Can Canada’s shaky constitutional structure weather the economic equivalent of SARS?

If the present global financial system built around the U.S. dollar collapses, a prospect that can no longer be dismissed as unthinkable and that some consider inevitable, history and common sense suggest that whatever new system emerges, it will give a greater and probably central role to gold. Then Canadians will rue the years they watched passively as the Bank of Canada unloaded their gold reserves for reasons that their government still refuses to tell them. A nation that enters a Kondratieff winter without gold is in the unenviable position of a squirrel without acorns as the days turn short, the nights long, and the weather cold.

Some argue that gold-producing nations have less need of gold reserves than others because they can always obtain the new production from their own mines should gold be required at some future time to meet an emergency. In Canada’s case, at current rates of production and assuming all newly mined gold were dedicated to the effort, it would take over four years fully to replace the gold reserves sold since 1985. However, in the conditions most likely to give rise to the need to replace those reserves, the more important issues would relate to price and means of payment rather than supply.

In any financial crisis arising from a worldwide loss of confidence in the U.S. dollar, gold prices could range from much higher than the present quote to “no offer,” particularly if other central banks have already loaned out as much of their gold as some believe, including this author. See, e.g., F. Veneroso, “An Update On The Commodity Case For Gold,” Gold Newsletter (September 2003); and J. Turk, “Correcting Disinformation,” GoldMoney Alert (August 6, 2003). What is more, the Canadian government’s financial resources under such circumstances would in all probability be under severe strain. Then the issue would become whether to expropriate the mines or their production using some sort of funny money.

In Canada as presently structured, where the provinces exercise principal authority over the natural resources within their borders, effective expropriation of the gold mines or their production would raise grave constitutional problems and almost certainly precipitate an immediate constitutional crisis with Quebec, the second largest provincial gold producer after Ontario.

7. The Northern Confederacy

[La Confédération du Nord]

To confront more effectively the strong United States that emerged from the Civil War, the Dominion of Canada was formed by the confederation of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia under the British North America Act, effective July 1, 1867, now incorporated in the Constitution Act, 1982.

Unlike the American constitution, which reserves to the states or to the people powers not expressly delegated to the federal government, the BNA Act confers on Canada’s central government powers not expressly delegated to the provinces. However, in the United States early decisions by the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Marshall favored a strong central government. Until 1949, final judicial authority with respect to the BNA Act rested with the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of the House of Lords, which frequently sided with the provinces. Thus today Canadian provinces exercise considerably more power than American states.

Some attribute this paradoxical development to the dead hand of Judah P. Benjamin, defender of states’ rights as U.S. senator from Louisiana before the Civil War and attorney general, secretary of war, and secretary of state for the Confederate States. After the war, the man known as “the brains of the Confederacy” fled to Britain, where he pursued an extraordinarily successful legal career and argued several early cases under the BNA Act before the Privy Council. However, the most important cases favorable to the provinces came later, suggesting that Benjamin’s role in establishing Canada’s tradition of strong provincial powers was indirect at best, the residual effect of the Privy Council and the London bar being introduced to federalism North American style by a forceful advocate of states’ rights. See C.O. Johnson, “Did Judah P. Benjamin Plant the “States’ Rights” Doctrine in the Interpretation of the British North America Act?” Canadian Bar Review (1967), pp. 454-477.

Confederation brought major change to Canada’s currency and banking systems, which were expressly assigned to the jurisdiction of the Dominion government under the BNA Act. See A History of the Canadian Dollar (Bank of Canada, October 1999). Dominion bank notes, redeemable in Halifax and St. John as well as Montreal and Toronto, replaced the various provincial currency issues, and the uniform currency of Canada became dollars fixed at $4.8666 to the British sovereign and $10 to the U.S. gold eagle.

However, the Bank of Canada did not open until 1935, more than twenty years after the establishment of the U.S. Federal Reserve, making Canada the last of the present G-7 nations to have a central bank. As explained in the recent report on the Bank of Canada’s handling of foreign gold during World War II:

[I]t had taken the collapse of national credit in the Depression and recognition that the gold standard no longer automatically regulated trade to dislodge the long-standing opposition on the part of Canada’s commercial banks to the notion of state-sponsored intervention in the credit and currency of the nation.

Under the Bretton Woods system the Canadian dollar was linked to gold through the U.S. dollar. When that system fell apart, both nations were left on unlimited paper money. Since then and absent the discipline of gold, the locus of political power has increasingly shifted toward Washington and Ottawa, each of which can meet financial obligations denominated in its own currency with the printing press, and away from the respective states and provinces, which must still exercise levels of fiscal discipline comparable to those of old.

But years of unlimited fiat money have taken their toll. What now emerges is the possibility that the U.S. dollar is a monetary HMS Titanic, with Captain Greenspan at the helm, the Bank of Canada’s David Dodge and other central bankers sailing first class, and the proletariat of Canada and the United States stuck in steerage. The question for the provinces is whether they can use their substantial powers under the BNA Act to devise for themselves and their citizens a potential monetary lifeboat should it be required.

The relevant grants of constitutional authority, or “heads of power” in Canadian legal terminolgy, are found in sections 91, 92 and 92A of the BNA Act.

Section 91 confers on the federal Parliament “exclusive Legislative Authority” with respect to a list of “Matters coming within the Classes of Subjects” enumerated, including: “The Regulation of Trade and Commerce” (item 2); “Currency and Coinage” (item 14); “Banking, Incorporation of Banks, and the Issue of Paper Money” (item 15, emphasis supplied); “Savings Banks” (item 16); “Bills of Exchange and Promissory Notes” (item 18); “Interest” (item 19); and “Legal Tender” (item 20). Section 91 also confers on that body residual authority “to make Laws for the Peace, Order, and good Government of Canada, in relation to all Matters not coming within the Classes of Subjects … assigned exclusively to the Legislatures of the Provinces.”

Section 92 lists the “Matters coming within the Classes of Subjects” on which the provincial legislatures have exclusive jurisdiction, including: “The Incorporation of Companies with Provincial Objects” (item 11); and “Property and Civil Rights in the Province” (item 13). Section 92A adds to this list non-renewable natural resources, forestry resources and electrical energy, including the “development, conservation and management of non-renewable natural resources … in the province, including laws in relation to the rate of primary production therefrom” (item 1(b), emphasis supplied). “Primary production” is defined inter alia as “product resulting from processing or refining the resource, and is not a manufactured product …” (item 5, Sixth Schedule, item 1(a)(ii)).

Under the U.S. Constitution (art. I, s. 10, cl. 1), the states cannot “make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts,” thus authorizing by implication state laws making gold or silver a legal tender. The BNA Act does not contain any similar authorization for the provinces, which thus appear foreclosed from making any laws regarding what may pass as legal tender.

8. From Greenbacks to Snowflakes

[Des Billets Verts aux Flocons de Neige]

Since the demise of the Bretton Woods system, the federal government of Canada like that of the United States has assumed the power to issue unlimited fiat money. And in Canada, just as in the United States, the highest court in the land has never opined on the constitutional authority, if any, for the exercise of this power, which finds no clear support in the BNA Act and is in flat violation of the U.S. Constitution, explaining why the U.S. Supreme Court has refused to address the matter. See Walter W. Fischer v. City of Dover, N.H., et al., Petition for Certiorari, Supreme Court of the United States, No. 91-221.

In its historical study referenced above, the Bank of Canada reports that the legal tender notes — “greenbacks” — issued by the American government during the Civil War “…fell from close to parity against the Canadian dollar in early 1862 to less than 38 Canadian cents (or Can$1 = US$2.65) in mid-July 1864, [which] represents the all-time peak for the Canadian dollar in terms of its U.S. counterpart.” By the end of the war, the greenback had almost doubled from its low, and thereafter continued to strengthen especially during 1866-1868 when many were retired. With the resumption of specie payments in 1879 at the pre-war rate, the Canadian and American dollars returned to parity, where they remained until the start of World War I.

Reading “the Issue of Paper Money” in head of power 91(15) against this history, it appears that the fathers of confederation intended to grant the same power to issue paper money to the new Dominion government as the American government was then claiming. However, as of the date of confederation in 1867, none of the Civil War legal tender cases had yet reached the U.S. Supreme Court, leaving the constitutional validity of the greenbacks in substantial doubt. Indeed, prior to the Civil War no one would have seriously challenged Daniel Webster’s view (Speech on the Specie Circular, U.S. Senate, December 21, 1836):

Currency, in a large and perhaps just sense, includes not only gold and silver and bank bills, but bills of exchange also. It may include all that adjusts and exchanges and settles balances in the operations of trade and business; but if we understand by currency the legal money of the country, and that which constitutes a legal tender for debts, and is the standard measure of value, then undoubtedly nothing is included but gold and silver. Most unquestionably there is no legal tender, and there can be no legal tender in this country, under the authority of this government or any other, but gold and silver, either the coinage of our own mints or foreign coins at rates regulated by Congress. This is a constitutional principle, perfectly plain and of the highest importance. The States are expressly prohibited from making anything but gold and silver a legal tender in payment of debts, and although no such express prohibition is applied to Congress, yet, as Congress has no power granted to it in this respect but to coin money and to regulate the value of foreign coins, it clearly has no power to substitute paper or anything else for coin as a legal tender in payment of debts and in discharge of contracts. Congress has exercised this power fully in both its branches; it has coined money, and still coins it; it has regulated the value of foreign coins, and still regulates their value. The legal tender, therefore, the constitutional standard of value, is established and cannot be overthrown. To overthrow it would shake the whole system. [Emphasis supplied.]

The first of the Civil War legal tender cases to reach the Supreme Court, Hepburn v. Griswold, 75 U.S. (8 Wall.) 603 (1869), endorsed this view. But the following year and after a change in the composition of the Court, the decision in Hepburn was reversed and the constitutionality of the greenbacks upheld in the Legal Tender Cases (Knox v. Lee and Parker v. Davis), 79 U.S. (12 Wall.) 457 (1870). The notion that their validity rested upon being a war measure was rejected in Juilliard v. Greenman, 110 U.S. 421 (1884), which provoked George Bancroft’s A Plea for the Constitution of the United States: Wounded in the House of its Guardians (1884), a widely read polemic devoted in large measure to rebutting the Court’s assertion (110 U.S. at 447):

The power, as incident to the power of borrowing money and issuing bills or notes of the government for money borrowed, of impressing upon those bills or notes the quality of being a legal tender for the payment of private debts, was a power universally understood to belong to sovereignty, in Europe and America, at the time of the framing and adoption of the Constitution of the United States.

None of these Civil War cases, however, authorized the federal government to issue unlimited fiat money. On the contrary, in the Legal Tender Cases, 79 U.S. (12 Wall.) at 553, the Court said:

It is said there can be no uniform standard of weights without weight, or of measure without length or space, and we are asked how anything can be made a uniform standard of value which has itself no value? This is a question foreign to the subject before us. The legal tender acts do not attempt to make paper a standard of value. We do not rest their validity upon the assertion that their emission is coinage, or any regulation of the value of money; nor do we assert that Congress may make anything which has no value money. What we do assert is, the Congress has power to enact that the government’s promises to pay money shall be, for the time being, equivalent in value to the representative of value determined by the coinage acts, or multiples thereof. … It is, then, a mistake to regard the legal tender acts as either fixing a standard of value or regulating money values, or making that money which has no intrinsic value. [Emphasis supplied.]

The concurring opinion of Justice Bradley emphasized the same point (id. at 560):

This power [to emit legal tender notes] is entirely distinct from that of coining money and regulating the value thereof. … It is not an attempt to coin money out of a valueless material, like the coinage of leather or ivory or kowrie shells. It is a pledge of the national credit. It is a promise by the government to pay dollars; it is not an attempt to make dollars. The standard of value is not changed. [Emphasis supplied.]

As a result of the Civil War legal tender acts, two different American dollars came into general circulation: paper and specie. They were described by the Supreme Court in Trebilcock v. Wilson, 79 U.S. (Wall.) 687, 694-695 (1871):

The note of the plaintiff is made payable, as already stated, in specie. … But here the terms, in specie, are merely descriptive of the kind of dollars in which the note is payable, there being two different kinds in circulation, recognized by law. They mean that the designated number of dollars in the note shall be paid in so many gold or silver dollars of the coinage of the United States. They have acquired this meaning by general usage among traders, merchants, and bankers, and are the opposite of the terms, in currency, which are used when it is desired to make a note payable in paper money. These latter terms, in currency, mean that the designated number of dollars is payable in an equal number of notes which are current in the community as dollars. [Emphasis in original; citations omitted.]

As this review of the American legal tender cases decided shortly after confederation shows, the power to issue paper money representing — however imperfectly — a metallic standard of value was regarded very differently from the power to issue unlimited fiat money. Under head of power 91(15) in the BNA Act, the new Dominion government was granted an express power covering “the Issue of Paper Money,” but there is nothing in the BNA Act to suggest that this grant included the power to issue unlimited fiat money with no reference whatsoever to a metallic standard of value. Notes of that nature would have been far worse than American greenbacks; they would have been Canadian “snowflakes” destined to melt over time with no chance of repayment in money having any recognized or identifiable standard of value.

Nor can the power to issue unlimited fiat money be found in the words “Currency and Coinage” as used in head of power 91(14). The Court in the Legal Tender Cases expressly disclaimed any assertion that the “emission [of legal tender notes] is coinage.” Giving “currency” the same meaning as the Court in Trebilcock, the power refers only to paper money. Thus the federal “Currency and Coinage” head of power does not support an implied federal power to require the exclusive use of an unlimited paper currency or to prohibit or unreasonably interfere with the use of gold or silver, especially in circumstances where the metals are held as protection against anticipated depreciation in the value of paper money or circulate in voluntary private transactions solely on the basis of weight.

Canada’s existing Currency Act does not mandate a different result. For while it requires all “public accounts” to be maintained in Canadian dollars (s. 12), it permits private contracts to be made in Canadian dollars or in “the currency of a country other than Canada” or “a unit of account that is defined in terms of the currencies of two or more countries” (s. 13). Since all currencies are defined today by the value at which they exchange in world markets, and since gold and silver in various specified weights exchange against all of them in markets around the globe, units of gold or silver — whether grams, ounces, other locally recognized weights, or fractions thereof — all fit within this authority.

Section 92A of the BNA Act grants broad and exclusive authority to the provinces over natural resources within their territories. Head of power 92(13) covers “Property and Civil Rights,” which in its literal and historic sense is “the entire body of private law which governs the relationships between subject and subject,” but this broad power is reduced under the BNA Act by withdrawing certain enumerated matters and placing them in the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government. See P.W. Hogg, Constitutional Law of Canada (4th ed. (looseleaf), vol. 1, s. 21.2).

However, in the area of financial institutions and banking, the constitutional dividing line is not fixed. There federal power is deemed exclusive only to the extent that it has been exercised. Thus federal power over banking has not prevented the provinces from chartering and regulating other financial institutions (e.g., trust companies, credit unions, caisses populaires) that perform essentially the same or similar functions as the federally chartered banks.

The provinces may also enact laws of general applicability to all financial institutions as long as they do not unduly burden or discriminate against the chartered banks or impose requirements on them that are inconsistent with federal laws. As Canada’s financial services industry has evolved, provincial regulation of the insurance industry is widespread and the securities industry is regulated exclusively at the provincial level. See id., s. 24; esp. discussion of Canadian Pioneer Management v. Labor Relations Board of Saskatchewan (1980) 1 S.C.R. 433, and Reference Re Alberta Statutes (1938) S.C.R. 100 (invalidating a Depression era comprehensive “social credit” scheme).

In summary, the Canadian constitution does not confer on the federal government any clear authority to issue unlimited fiat money. Neither the constitution nor the Currency Act erects any clear or obvious bar to provincial legislation designed to support and encourage the use of gold within the province, whether in connection with savings, retirement or insurance plans or in voluntary exchange for goods or services. What is more, there is express constitutional support for provincial legislation to encourage the use of gold if that legislation is tailored to promote “development, conservation and management” of gold deposits within the province and does not unduly interfere with any authorized exercise of federal power.

9. New Deal Light

[«New Deal» Léger]

Much of the New Deal legislation proposed in Canada during the 1930’s was held invalid by the Privy Council, which declined to give an expansionary interpretation to the federal government’s residual authority under the “Peace, Order, and good Government” clause (“p.o.g.g.” clause). As a result, Ottawa’s regulatory authority over trade and commerce at the national level is significantly more circumscribed than Washington’s, and the provinces necessarily play a much larger role in regulating the economic and business life of the nation than do the American states. See Hogg, supra, s. 17.4(a).

However, none of the New Deal litigation in Canada involved currency issues, and there is no Canadian analogue to the Gold Clause Cases, 294 U.S. 240 (1935). Canada made no effort to confiscate gold in the possession of its citizens or to prohibit private ownership of gold. Although the federal government and at least two provinces passed statutes to alleviate the burden of gold clauses in private and public contracts, none of this legislation appears to have produced reported decisions. Interestingly, the gold clause statutes remain on the books in Nova Scotia (Gold Clauses Act, R.S., c. 186) and Manitoba (Gold Clauses Act, C.C.S.M. c. G60), a reminder that the provinces have in the past claimed broad powers with respect to regulating the monetary use of gold.

Generally speaking, the p.o.g.g. clause authorizes the federal government to act on: (1) matters falling in gaps not covered by the express distribution of powers between the federal Parliament and the provincial legislatures; (2) matters of national concern provided that in each case the subject is sufficiently distinct to qualify as a discrete “matter” separate and apart from those delegated to provincial jurisdiction; and (3) matters presenting national emergencies such as war or insurrection, but then only on a temporary basis. See Hogg, supra, ss. 17.2 (gap), 17.3 (national concern), and 17.4 (emergency). In its historical study of the Canadian dollar, the Bank of Canada notes that foreign exchange controls were imposed under the War Measures Act in World War II but not in World War I.

In an effort to control inflation, the federal government in 1975 passed temporary wage and price controls to expire in 1978 unless sooner terminated or extended. In Reference Re Anti-Inflation Act (1976), 2 S.C.R. 373, the Supreme Court of Canada declined to view this legislation as dealing with a matter of national concern having the requisite distinctness, but upheld the act because, as the Chief Justice explained (at 425):

In my opinion, this Court would be unjustified in concluding, on the submissions in this case and on all the material put before it, that the Parliament of Canada did not have a rational basis for regarding the Anti-Inflation Act as a measure which, in its judgment, was temporarily necessary to meet a situation of economic crisis imperilling the well-being of the people of Canada as a whole and requiring Parliament’s stern intervention in the interests of the country as a whole.

Summarizing the federal government’s authority under the p.o.g.g. clause as currently construed in Canadian jurisprudence, Dean Hogg writes (supra, s. 17.5):

First, it gives to the federal Parliament permanent jurisdiction over “distinct subject matters matters which do not fall within any of the enumerated heads of s. 92 and which, by nature, are of national concern”, for example, aeronautics and the national capital region. Secondly, the p.o.g.g. power gives to the federal parliament temporary jurisdiction over all subject matters needed to deal with an emergency. On this dual function theory, it is not helpful to regard an emergency as being simply an example of a matter of national concern. As Beetz J. said, “in practice the emergency doctrine operates as a partial and temporary alteration of the distribution of power between Parliament and the provincial Legislatures.” [Emphasis in original; citations omitted.]

In any future global monetary crisis, there is little question that the government of Canada has constitutional authority without resorting to the p.o.g.g. clause to modify, change or reform the unlimited fiat money system that it has created, including the reestablishment of some form of linkage between paper money and gold. In the latter event, however, should the federal government try to use the p.o.g.g. clause effectively to commandeer the gold resources under provincial jurisdiction, it could do so only temporarily, hardly a sound basis for permanent monetary reform.

What is more, the exercise of such emergency authority would have to take account of likely practical constraints, especially if there were significant opposition from the gold-producing provinces. The federal government’s actions with respect to gold over the recent past have scarcely endeared it to the gold mining community, which might at long last decide actively to resist further depredations from Ottawa.

Strong opposition to any federal gold grab in Quebec would present an even dicier situation. At a minimum, it would hand the PQ a cause célèbre on which to mount a new referendum campaign. If events started to slip out of control into civil disobedience, a second peacetime proclamation of the the War Measures Act in Quebec could provide the spark for outright rebellion. Used in both world wars, this act has been invoked only once peacetime: to deal with an “apprehended insurrection” in October 1970 following the kidnapping of a British diplomat, later released, and a Quebec cabinet minister, later murdered, by the Front de Libération du Québec, a violent separatist organization.

Widely regarded in Quebec (and elsewhere) as an excessive suspension of civil liberties not justified by the activities of a relatively minor splinter group, this use of the War Measures Act produced some litigation in the lower courts but no definitive consideration of its constitutionality. However, the Quebec government later compensated many who were arrested but not subsequently charged or who claimed to have suffered other police mistreatment under this episode of martial law.

10. Grams of Common Sense

[Le Bon Sens en Grammes]

While international policy makers have done virtually nothing to reform a global paper currency system that appears headed toward complete breakdown, technology and the Internet have enabled the rebirth of real global money — gold — in a far more efficient, practical and safe form than possible in earlier times.

A leading innovator in this regard is GoldMoney.com, which has created a digital gold currency that circulates electronically over the Internet with relatively low transaction costs among the system’s users on a 24/7 basis while at the same time representing physical gold in equal amount held in allocated storage. GoldMoney offers a safe and secure way to make immediate and non-repudiable payments in grams of gold (31.1034 grams equal one ounce), making it the functional equivalent of payment in gold coin in centuries past but avoiding the minting costs and other practical inconveniences associated with specie payments.

Both “GoldMoney” and “goldgram” are registered trademarks, and a GoldMoney “goldgram” is unique in that it circulates electronically through GoldMoney’s patented system. However, the concept of using grams of gold (or any other specific weight of gold) as money is neither patentable nor foreclosed to further development by others in non-infringing ways, e.g., minting coins or wafers denominated in grams, operating certificate or other gold accumulation plans in grams, offering exchange traded funds with each share representing one gram, or pricing goods and services in grams along with, or even in substitution for, national currencies. Henceforth, “gold gram” (two words) is intended in a generic sense whereas “goldgram” (one word) refers to the unit of account at GoldMoney.

A gold gram is simply a weight of gold unencumbered by a prescribed relationship to any national currency. Its value comes not from national legal tender laws but from its usefulness as a commodity. GoldMoney’s goldgrams are, and any gold gram theoretically is, divisible into 1000 mils for precision in individual transactions. At a gold price of US$311/ounce, one gold gram equates to $10 and one mil to one cent, making them as (or more) convenient for pricing goods and services as dollars and cents or other national currency units.

Certain features of GoldMoney’s system deserve further mention because they illustrate not only how technology and the Internet have made transactions using gold as the medium of exchange practical, convenient and economic, but also how they have provided solutions to the major risks and problems associated with fractional reserve banking under the gold standard.

GoldMoney’s fees and transaction costs are relatively low and highly competitive with other payments systems. Goldgrams can be purchased through Kitco, where the per ounce equivalent prices for goldgrams can be compared to those for other bullion products. Recently, Kitco has offered goldgrams at less than a 2% premium to COMEX gold in New York and at a lower premium than Krugerrands, the least expensive of the one ounce bullion coins. Redemptions back into major national currencies are typically made at less than a 2% discount to spot, keeping the full cost of a round turn to under 4%.

Transactions in goldgrams currently incur a processing charge to the user’s account in an amount equal to 1% of the payment requested, but not less than 10 mils nor more than 100 mils per transaction, making GoldMoney highly competitive with bank wire charges of US$15 to $30 or credit/debit card fees to merchants of 1% to 4%. Cross-border transactions conducted in goldgrams eliminate entirely spreads and commissions on foreign exchange. Electronic transfer eliminates the costs of shipping and handling physical gold.

Unlike a fractional reserve banking system in which the depositors’ gold is effectively on loan to the bank and thus subject to credit risk, goldgrams represent stored physical gold in equal amount held under bailment for the account holder, thereby eliminating credit risk and most forms of settlement risk. While the gold in individual user accounts represents unallocated, undivided proportional interests in the pool of gold containing all user accounts, the total pool is held in allocated storage in the form of 400 ounce bars meeting London good delivery standards and subject to various safeguards, including vault insurance and independent third party verification of user accounts.

Except for large commercial accounts, GoldMoney currently charges a vault or storage fee of 100 mils per month regardless of account size. At this rate, annual vault charges on one kilogram (1000 goldgrams or 32.15 ounces) would amount to 0.12%, and on 100 ounces to less than .04%. According to its report as of June 30, 2003, GoldMoney had users in over 100 countries. However, at present its goldgrams cannot be used to make payments other than between or among GoldMoney’s account holders, making the creation of some sort of debit card that would allow payments from user accounts to non-users in various national currencies a desirable next step.

At least one Canadian gold mining company, IAMGOLD, has announced a gold money policy that encompasses both holding the bulk of its discretionary corporate funds in allocated gold and paying dividends at the shareholder’s choice in Canadian dollars or gold, possibly using GoldMoney to effect the latter. Thus even in ordinary business transactions, Canada’s ersatz hard money coins — the looney and the tooney — could soon face potential competition from real money of gold.

11. Sword in the Shield

[L’Épée dans le Bouclier]

According to one wag, the basic problem in the Canadian energy industry is geographic: all the oil is in the west but all the dipsticks are in Ottawa. A similar problem affects its gold mining industry: all the gold is in the great Pre-Cambrian shield that hosts Canada’s mineral wealth but the most powerful gold-diggers are in the nation’s capital with the dipsticks.

The Canadian government has dropped its shield of monetary gold for the paper sword of U.S. dollars. The provinces with gold deposits can follow suit by falling on the golden swords within their reach. Or they can draw them, using the resources and constitutional tools which they possess to position their citizens to survive and prosper in a post-dollar world where permanent, natural money of gold plays a much larger role than it has in the recent past.

Since the Canadian dollar is no longer defined with reference to a weight of gold, and since gold bullion coins from foreign jurisdictions are allowed to trade and circulate freely in Canada alongside its own Maple Leaf gold coins, there does not appear any sound practical, legal or constitutional objection to the provinces authorizing coins or wafers minted from gold mined within their borders and denominated solely in gold grams or some other convenient weight of gold such as ounces. Because grams appear more suitable than ounces for smaller transactions as well as equally suitable for larger ones, the gram unit is employed in the remainder of this essay as a shorthand expression for any convenient weight of gold and without intent to exclude ounces in uses where they might be preferred.

Of course, a province cannot charter a “bank” to issue gold grams. Nor can a province make gold grams legal tender or assign them a value expressed in Canadian dollars, as is the practice under the federally authorized Maple Leaf coin program. See the Royal Canadian Mint Act. What is more, any provincial gold coin or wafer program would have to comply with the Precious Metals Marketing Act, which is intended to protect buyers of these items and in certain circumstances authorizes the use of a national quality mark consisting of a maple leaf surrounded by the letter C.

Minting physical gold grams and encouraging their use within the province would likely stimulate greater interest in and demand for paper gold grams. Certificates denominated in gold grams might be offered by provincial institutions under regulations designed to assure sufficient backing, preferably by gold mined in the province. Another possibility would be exchange-traded funds denominated in gold grams. In all probability, growing use of physical and paper gold grams would interact in mutually supportive ways with the use of electronic gold grams like those offered by GoldMoney.com. To accelerate growth in this area, provincial merchants could be motivated with or without formal legislative action to participate in payments systems utilizing electronic gold grams.

Targeted support for provincial gold mining could involve programs other than flow-through shares, which often waste a lot of money on tax breaks for wealthy investors without producing much in the way of new mines, permanent jobs, or future tax revenues.

Coin or wafer programs could include financial incentives to encourage delivery of gold mined in the province to its designated mint. During periods of severely (or artificially) depressed gold prices, effective price supports could be implemented — as they were by the federal government during the era of the London gold pool — to discourage high-grading, which often makes physical access to the lower grades of ore left behind much more difficult if not impossible, and in any event reduces the average grade of what remains to the point where much higher gold prices are needed to justify mining it.

Indeed, in the event of a legal challenge by the federal government to provincial gold gram programs, the provinces might well consider the possibility of a counterclaim for reparations on account of injury to provincial ore bodies caused by the federal government in recent years. Even assuming that all the Bank of Canada’s gold sales prior to the 1995 Quebec referendum were carried out for sound and justifiable reasons, the subsequent sales of Canada’s last hundred tonnes — frequently at prices under $300/oz. in support of the central banks’ scheme to suppress gold prices — was and is indefensible.

As officials in a major gold-producing nation with great mining expertise, those responsible for the sales must have known that as a direct consequence of the unanticipated and artificially low gold prices at which they were made, high-grading was inflicting substantial and probably irreparable damage on the ore bodies of many of Canada’s working gold mines. What is more, these sales were utterly incompatible with prudent management of the nation’s official reserves. Having already sold off most of its gold, Canada should have seized the opportunity that low gold prices presented to bring its gold reserves back to levels more consistent with those in other G-7 countries.

To the extent that provincial gold gram programs involve subsidies, they should be tailored to meet the requirements of NAFTA, which permits non-discriminatory measures with legitimate objectives particularly when related to environmental concerns or the management of natural resources. Because gold grams derive their value solely from their weight and do not link to any national currency except through the gold and foreign exchange markets, gold gram programs even at a national level would not run afoul of the Second Amendment to the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, which prohibits member countries from linking their currencies to gold.

Today low risk short-term instruments offer negligible yield. Higher yields are available at longer maturities but at much higher risk, especially given existing inflationary pressures. Under these circumstances, gold is primed for rapid appreciation against all paper currencies. Provincial gold gram programs have the potential both to accelerate the rise in gold prices and to bring the benefits of the upturn to a broad segment of the provincial population. See J. Embry, “15 Fundamental Reasons to Own Gold,” GoldMoney Alert (September 26, 2003).

12. Québec Libre