Dr. and Mrs. Howe were married in the fall of 1904. Mrs. Howe’s father had died the previous year, and the youngest of her six siblings, William Torrey Barker, Jr., was not yet ten. Not surprisingly, then, the young couple soon found themselves supervisors of a Middlesex dormitory that included among its charges her brother Bill.

One of his classmates was James P. Warburg, who would later earn fame as President Roosevelt’s principal monetary advisor, and then notoriety as FDR’s most outspoken monetary critic. The young Warburg was the son of the banker Paul Warburg, frequently regarded also as the father of the Federal Reserve Bank.

In later life, Jimmie Warburg wrote an autobiography, The Long Road Home – The Autobiography of a Maverick (Doubleday, 1964), which gives a brief description of his time at Middlesex (pp. 25-27):

Dr. Reginald Heber Howe—known as “Doc” or “Heber”—was my housemaster. His wife, the sister of my classmate, Bill Barker, besides being the mother of two children, was half mother and half older sister to all the boys in Hallowell House. She was the perfect feminine antidote for homesickness. Doc Howe introduced me to botany, forestry, and natural history. Under his guidance, Charles Windsor, the Boss’s son, and I wrote a paper on the Usneaceae of North America (lichens) which the Doc had printed and distributed to the members of the Massachusetts Botanical Society. Doc was also the rowing coach and managed for years to train future Harvard varsity oarsmen on the school’s half-mile pond. Later he founded and became the first headmaster of the Belmont Hill School.

* * * * *

My closest friends at Middlesex were Alan Clark, Eric Douglas, John Morgan, and Bill Barker. We decided to room together at college. There were then no freshmen dormitories and no house system. Freshmen lived wherever they could find rooms, and none of my four friends had well-to-do parents. When my father generously offered to give me whatever allowance I wanted, I told him that I would like a hundred dollars a month, which was what my friends would have to cover tuition, books and living expenses. My father thought this “quixotic” but my mother supported me.

Graduating from Harvard in June 1917, Uncle Bill worked briefly in a bank before finding himself a member of the American Expeditionary Force. Arriving in France as an artillery officer, he participated in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Discharged in 1919, he spent most of 1920-21 traveling around the world with his sister Louisa. After starting his teaching career at Middlesex, he joined the Belmont Hill faculty in the fall of 1926, a year after Finch Keller and a year before Charlie Jenney.

Mr. Jenney remembered Uncle Bill “for his inspiring teaching,…a most understanding teacher…and friend to many students of the early thirties” (Duncan, p. 45). Coach of varsity baseball from 1927 until 1932, Uncle Bill was also an enthusiastic participant in intramural athletics after hockey season. As Mr. Keller recounted (Duncan, p. 61):

[W]e had a so-called cage in which a game that was a combination of football and basketball was played. Early graduates will remember the unstoppable rushes of Mr. Fay and Mr. Barker who clasping the ball to their chests would bull their way through masses of players right up to the basket and miss.

From his student days, Henry Sawyer ’32 recalled living at The Farmhouse, just down Prospect Street from the School, where Uncle Bill was dormitory master: “Bill Barker was a wonderful person—an English teacher and at one time Director of the Lower School—and Jane Barker, his wife, a most interesting person and a very good friend of the boys.” (Duncan, p. 50)

Under Hal Taylor, the Lower School was established as a separate unit in the old portable building, which was upgraded by the addition of a classroom and an office for Mr. Barker, its first director.

In May 2019, John L. Middleton ‘44 returned for his 75th reunion, at which time I had the pleasure of talking with him. In discussing the faculty of his era, he counted Bill Barker as the most important to him personally because “…he recognized early on that I had a problem with what is now recognized as dyslexia and helped me to overcome it.” At dinner that evening the B-Flats sang Fly Me to the Moon, but only John had any real experience in that regard, having designed and built certain devices for the Apollo lunar landers.

Uncle Bill died in 1938 at the age of 42 from heart failure brought on by familial hypercholesterolemia, a inherited disorder that has plagued the Barker family. Eleanor Morse, wife of the Headmaster, wrote a tribute that first appeared in The Sextant, quoted in full in Roger Duncan’s history of the School (Duncan, pp. 91-92), and in large part in the Harvard 25th Reunion Report of the Class of 1917:

Bill had at least two of the gifts that qualify a man for the difficult and exacting order of friendship. He could lead people to talk in a way that enabled them not only to express but to ‘get onto’ themselves; he was interested in and fond of his friends for what they were, faults and all. He did not preach much, but he started them looking at themselves, as he did at them, in a complete picture with the wickedness included. He knew that no boy or woman can be truly mature without ripening all through like a good fruit. Like a good teacher and a true friend Bill could give reassurance of his affection and interest, while making a person recognize and accept his own weakness as part of a good and growing whole.

His older friends valued these same qualities in Bill all the more because they knew that his own maturity had not come to him without pain and struggle. As a boy, and as a young man during and after the war, he suffered and fought with disillusionment and disgust; and his was always the private conflict of one who tries to reconcile a sensitive nature with a skeptical intelligence. He grew to great and wise tolerance of human failing, but preserved a shriveling intolerance of anything he took to be a sham.

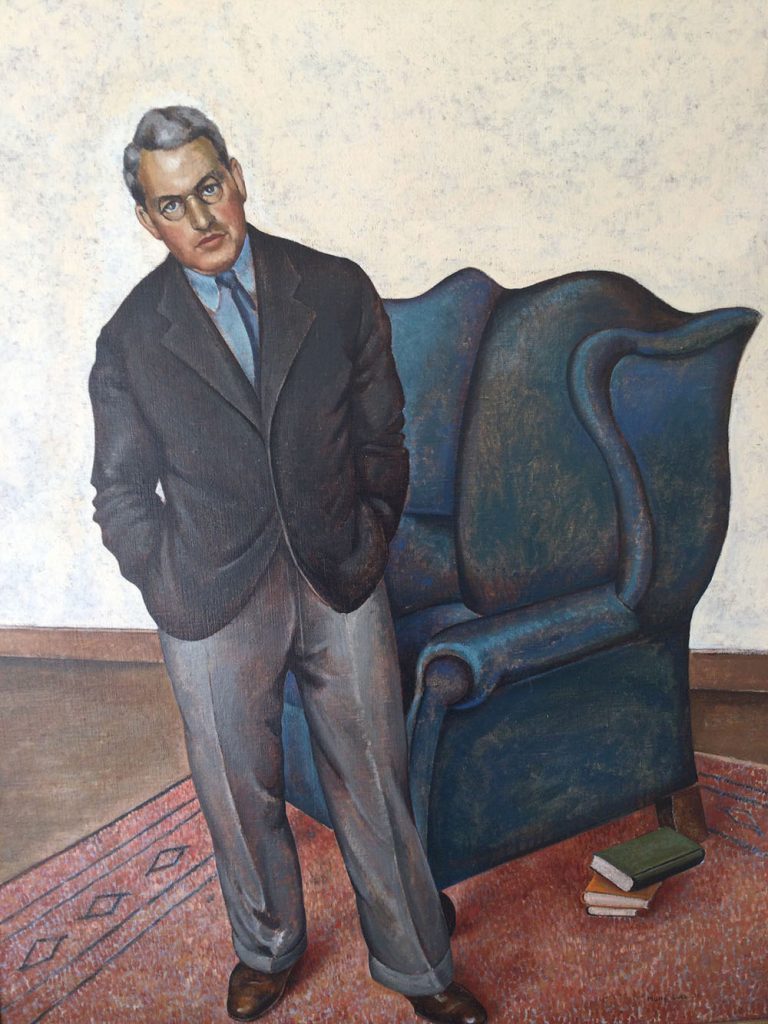

Divorced from his first wife in 1934, Uncle Bill at the time of his death was engaged to Grace Reasoner, a Belmont neighbor and free lance artist. It would have been a second marriage for both, making Uncle Bill a stepfather to three young girls. Both were also friends of another local artist, Molly Luce, who not long before Uncle Bill’s death painted his portrait. Who had the idea for the portrait, or whether it was commissioned by his sister, Mrs. Howe, has been lost to time. But whatever the case, after his death, Mrs. Howe determined that the portrait should go to his bereaved fiancé.

Some years later, Grace Reasoner remarried. Molly Luce retired with her husband to Little Compton, Rhode Island, where she became a close friend of Virginia Lynch, owner of a local art gallery, who assisted in the exhibition and sale of some of Molly’s works, and upon Luce’s death in 1986, the distribution of the art still in her estate, which as it turned out included the portrait of Uncle Bill.

My father, indeed the whole Howe family, has summered in Little Compton since the late 1940’s. Sometime during the administration of Molly Luce’s estate, Virginia Lynch met my father at a cocktail party in Little Compton and made the family connection between Uncle Bill, Dad, and the portrait, which she then gave to my father. Thus after almost half a century, the portrait returned to the family.

Uncle Bill Barker, quintessential teacher, by Molly Luce, circa 1938: