Much have I traveled in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen.

–John Keats, On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer

The world changed on Wednesday, June 20, 2007. This was the day when Merrill Lynch, as creditor, attempted to auction off $850 million face value in securities seized from two Bear, Stearns hedge funds. Some of these securities were collateralized by subprime mortgage assets; most were backed by more highly rated obligations. The auction was a failure. Only $100 million in face value were sold, at prices reflecting a substantial discount, and such bids as were received on the balance were reportedly derisory. Merrill Lynch subsequently canceled a planned follow-up auction of similar securities, but the cat was out of the bag: Wall Street has been living in a land of make believe.

The crisis of confidence that began with Bear, Stearns and will ultimately end, we expect, in the serial collapse of the fiat monies of the world, has prompted a flight to safety and called into question the integrity of collateral underlying financial assets everywhere.

Against this backdrop, we thought it time to have a closer look at streetTRACKS Gold Shares (“GLD”). With its backing of real money, the very antithesis of the dreck inside the typical Wall Street sausage, GLD would seem to be just what the doctor ordered.

The market certainly thinks so. Since its rollout back in November 2004, GLD has been a brilliant success. From just 300,000 Shares at inception, representing interests in 30,000 ounces of gold, the total number of Shares outstanding as of September 28, 2007, had grown to 187,900,000, representing interests in 18,584,096 ounces (578 tonnes) of gold. To put this quantity of gold into perspective, if GLD were a central bank, it would be the world’s eleventh largest official holder of gold. Just as intended, GLD has reflected the performance of the price of gold bullion, less expenses, in a highly liquid instrument.

And yet, certain aspects give us pause.

A Declaration of Bias

Before deconstructing GLD, it is only fair that we declare our bias in favor of a vision of an ideal gold-backed security. This imaginary instrument, fairly or unfairly, is the benchmark lurking in the background, so we may as well articulate it.

Our ideal security would be a simple and transparent flow-through ownership interest in metal stored safely in a safe location. It would have a minimum of relevant parties and clear lines of accountability. Ownership interests in the gold would be evidenced by certificates that the individual investor could, if he so chose, keep in a drawer at home or in a safe deposit box. The structure would facilitate the exchange by all investors, retail and institutional alike, of their intangible ownership interests for units of the underlying metal.

In other words, it would look a lot like a currency backed by 100% reserves under a gold coin standard. Indeed, it would look a lot like currency that actually circulated throughout the developed world under the classic gold standard up until the outbreak of World War I. Only better: it would disintermediate the central bank and eliminate the fraud of fractional reserves. That is to say, it would look a lot like what we hope will someday emerge out of the rubble of the fiat monies.

But the architects of GLD, whom we salute for their vision and perseverance, were constrained to design a product that would work in today’s still-functioning Alice in Wonderland monetary system, where money is what the Red Queen says it is. The concessions needed to get a gold investment product launched at all probably lie beneath the features that differ most markedly from those of our bel ideal.

The structure is economically simple but legally complicated, with numerous relevant parties and murky lines of accountability. The securities are just entries in a computer database, with no tangible representation. Retail investors are effectively barred from exchanging their ownership interests for units of the underlying metal. And even institutional investors must operate through a not-so-priestly caste of intermediaries, if they wish to obtain the underlying asset.

In other words, continuing our monetary analogy, GLD looks a lot like a bullion exchange standard, not a gold coin standard. A bullion exchange standard is an insiders’ game in a wholesale market: unless you are a member of the central bank’s inner circle, you can’t swap your paper for gold. The very point of such a system is to take gold out of circulation, and put it under centralized control.[1]

Indeed, GLD seems to reflect the fine hand of a guiding intelligence determined to ensure it could never become or inspire – a money substitute or successor. Fair enough; one financial era at a time. The trouble is, the same features that prevent it from ever becoming money, prevent it from realizing its full potential as a safe haven investment. More troubling still, we see reason to worry about the safety of the underlying metal, given the neighborhood where it is stored.

The Model Warehouse

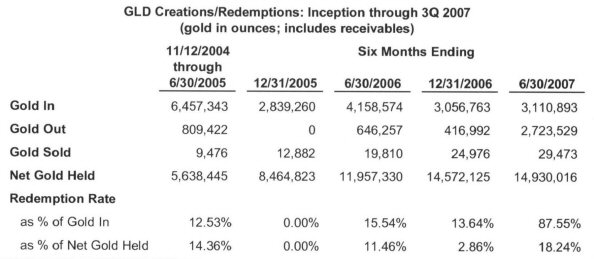

GLD is a passive investment trust. That is, it doesn’t do much. The underlying economic model is that of a warehouse in which gold periodically gets deposited in exchange for claim checks, and claim checks periodically get presented for gold. From time to time the boys in the warehouse sell a little gold, just to keep body and soul together. You can see how it functions on a daily basis by looking at the data on its website. You can see how it has functioned through June 30 of this year, bigger picture, in the following reconstruction (based on information contained in GLDs quarterly SEC filings and believed to be reliable, but not independently verified):

In our model, “Gold In” reflects deposits made in the warehouse; “Gold Out” reflects withdrawals; “Gold Sold” reflects fees and expenses, paid with the proceeds of sales of gold; and “Net Gold Held” reflects the cumulative ending balance after giving effect to sales and redemptions. “Redemption Rate” expresses Gold Out as a percentage, first, of Gold In, and second, of Net Gold Held.

Although the model itself is simple, you need a scorecard to follow the players. The warehouse is operated by the London branch office of HSBC US N.A. (“HSBC”), a US subsidiary of HSBC Group PLC, a large UK bank. HSBC operates the warehouse in its capacity as Custodian, and answers to the Trustee, as agent for the record owner of the deposits, the Trust. The Trust is a New York investment trust, the creature of an agreement between the Sponsor of the Trust, a Delaware subsidiary of the World Gold Council, itself a Swiss non-profit entity, and the Trustee, The Bank of New York, a New York bank. The agreement between the Sponsor and the Trustee, known as the Trust Indenture, is the basic charter for the Trust. The gold is deposited, stored and withdrawn in accordance with the terms of a set of contracts between the Custodian and the Trustee, known as the Allocated Bullion Account Agreement (the Custody Agreement) and the Unallocated Bullion Account Agreement.[2] Upon receiving gold deposits, the Trustee causes the Trust to issue, in exchange, units of undivided interest in the Trust, i.e., the Shares, reflecting the net value of the new addition. The Shares are in turn listed on the New York Stock Exchange and marketed to institutional and retail investors in the United States.

The Marketing Agent for the Shares, State Street Global Advisors, maintains the website for the Trust, which posts extensive data relating to the Shares, as well as information relating to the underlying gold itself.

Threshold Issues

With that brief sketch of the economics and structure out of the way, we can move on to a more detailed consideration of this instrument.

Little Guys Need Not Apply

As noted earlier, we would have preferred full convertibility by all investors. GLD, insofar as the withdrawal feature is concerned, is an institutional deal. The Prospectus is quite clear that only Authorized Participants, about which more later, can effect an exchange. Curiously, the GLD FAQs seem to hold out the possibility that individual investors can swap their paper for gold by pooling their investments with those of other individual investors:

1. Can you take physical possession of the gold?

The Trustee, Bank of New York, does not deal directly with the public. The trust handles creation and redemption orders for the shares with Authorized Participants, who deal in blocks of 100,000 shares. An individual investor wishing to exchange shares for physical gold would have to come to the appropriate arrangements with his or her broker. [Emphasis supplied.]

But if our own futile attempts are any guide, there is neither mechanism nor precedent for it. Try it yourself, if you have a mildly sadistic streak. Ask your broker to make due inquiry as to how you can pool your Shares with those of others to effect an exchange. This is tantamount to sending him on a snipe hunt. Nobody will know. Nobody will ever have thought about it, as it will never have come up before. Five different people in as many different departments will be consulted, and none will have a clue. The compliance issues alone will cause major headaches among the legal staff. The matter will be quietly dropped. No, exchange is just for large institutions. But even if you are a large institution, you will need to have a bullion trading account with an Authorized Participant, not just a securities or commodities account. If you don’t have one of these already, setting one up is no simple matter, particularly for foreign entities.[3]

Is the Gold Even There?

When GLD was first launched, the language in the Custody Agreement created a troublesome level of exculpation, and an even more worrisome structural weakness.

Certain key clauses read, in pertinent part (“we” is the Custodian; “you” is the Trustee):

7.4 LOCATION OF BULLION. Subject to clause 8.1, the Bullion held for you in your Allocated Account must be held by us at our London vault premises or by or for any Sub-Custodian, unless otherwise agreed between us. [Emphasis supplied.]

8.1 SUB-CUSTODIANS: We may select Sub-Custodians to perform any of our duties under this agreement including the custody and safekeeping of Bullion. The Sub-Custodians we select may themselves select subcustodians to perform their duties, but such subcustodians shall not by such selection or otherwise be, or be considered to be, a Sub-Custodian as such term is used herein. We will use reasonable care in selecting any Sub-Custodian. [Emphasis supplied.]

In other words, the Custodian had the right to appoint subcustodians to hold the gold, who in turn could appoint sub-subcustodians, but the Custodian did not have the obligation, or in some cases even the right, to follow up or supervise. Aside from the Custodian’s obligation to use commercially reasonable efforts to obtain delivery of gold held by subcustodians when necessary, the Custodian would not be liable for the acts or omissions, or for the solvency, of any subcustodian it selected, unless it had acted negligently or in bad faith.

This nettlesome language, together with the fact that the Bank of England was one of the named subcustodians, about which more later, prompted a hail of negative inferences and acid commentary.[4]

Perhaps in response to that criticism, in December 2005 the Trustee and the Custodian quietly tightened up the offending provisions of the Custody Agreement to provide that subcustodians were permissible only for gold in transit, and that the default location for the Trust’s gold would always be the Custodian’s vaults:

7.4 LOCATION OF BULLION. Unless otherwise agreed between us, the Bullion held for you in your Allocated Account must be held by us at our London vault premises or, when Bullion has been allocated in a vault other than our London vault premises, by or for any Sub-Custodian employed by us as permitted by Clause 8.1 We agree that we shall use commercially reasonable efforts promptly to transport any Bullion held for you by or for a Sub-Custodian to our London vault premises and such transport shall be at our cost and risk. We agree that all delivery and packing shall be in accordance with the Rules and LBMA good market practices.

8.1 SUB-CUSTODIANS: We may employ Sub-Custodians solely for the temporary custody and safekeeping of Bullion until transported to our London vault premises as provided in Clause 7.4, unless otherwise agreed between us with the consent of the Sponsor. The Sub-Custodians we select may themselves select subcustodians to provide such temporary custody and safekeeping of Bullion, but such subcustodians shall not by such selection or otherwise be, or be considered to be, a Sub-Custodian as such term is used herein. We will use reasonable care in selecting any Sub-Custodian. [Emphasis supplied.]

So what should we make of this? For our part, we have a fair degree of confidence that the gold is actually there.

We take comfort from the fact that the Trust publishes a detailed list of specific bars of gold held by the Custodian, updated every Friday afternoon. As of September 28, the list ran to 466 pages. A scam in which the bars were faked would be intricate, burdened by a high risk of exposure, and fraught with potential for embarrassment of some very prominent institutions, the very anchors of the global monetary system. There are a number of fairly critical eyes that monitor this list for just the sorts of discrepancies that might indicate a fraud.[5]

We take further comfort from the existence of the redemption data in our model above. The data are contained in SEC filings on which a number of people with potential liability have to sign off. Even in today’s lax regulatory environment, there can be unpleasant personal consequences for making false statements of material fact in such filings.

Finally, we take some comfort from the probability that, even if we were to assume there is skullduggery afoot, it would make sense to think bigger. The purpose of a scam, given the stature of the players and the logic of the situation, would be more than about making money; these players can make all the money they want under special patent from the state. Just ask Goldman Sachs. Rather, the purpose of a scam would likely be patriotic, bordering on altruistic; namely, to help the central banks manage the price of gold in support of the fiat monetary system. We were horrified to learn about this practice from a recent Citigroup research report:

Central Banks: Capitulating on Gold?

Official Sales ran hot in 2007, offset by rapid de-hedging “Gold undoubtedly faced headwinds this year from resurgent central bank selling, which was clearly timed to cap the Gold price. Our sense is that central banks have been forced to choose between global recession or sacrificing control of Gold, and have chosen the perceived lesser of two evils. “

If we are to take Citigroup’s conspiracy theory at face value, the point presumably would be to gather metal under centralized control, where it could be mobilized as needed to meet the excess demand in the physical market arising from a chronic and stubborn mispricing of the asset. To serve this end, metal needs to be where it is supposed to be. Perhaps we see some support for this theorem in the redemption data for the first half of 2007: does that high redemption rate signify a draft of all able-bodied metal for the Battle of $640?

Is It the Right Stuff?

A second threshold issue is the quality of the gold on deposit. As we shall see, there is good gold, and not so good gold. The Prospectus contains an ominous risk factor:

Neither the Trustee nor the Custodian independently confirms the fineness of the gold allocated to the Trust in connection with the creation of a Basket. The gold bullion allocated to the Trust by the Custodian may be different from the reported fineness or weight required by the LBMAs standards for gold bars delivered in settlement of a gold trade (London Good Delivery Standards), the standards required by the Trust. If the Trustee nevertheless issues a Basket against such gold, and if the Custodian fails to satisfy its obligation to credit the Trust the amount of any deficiency, the Trust may suffer a loss.

The Custody Agreement provides for recovery by the Trust in the event the Custodian misrepresents the fineness of gold admitted, and there is no time limit on a claim. So as long as the Custodian is still with us, someone at least is on the hook. Also, just as in the case of the other threshold issue, there would be little point in gathering up a lot of painted lead bricks, just to have them get rejected by the Market. As we’ll see, even the Bank of England has trouble passing bad metal in the Market.

All that said, we must concede that the matter is not free from doubt, as nowhere in the public filings relating to GLD have we been able to find the magic words, physical count uttered by an independent public accountant. The Custody Agreement gives the Trust’s accountants, Deloitte and Touche, the right to access the gold:

2.6 ACCESS: Upon reasonable prior written notice, we will, during our normal business hours, allow your representatives, not more than twice during any calendar year, and your independent public accountants, in connection with their audit of the financial statements of the streetTRACKS(R) Gold Trust, to visit our premises and examine the Bullion and such records maintained by us in relation to your Allocated Account as they may reasonably require.

And the FAQs refer specifically to this right of access:

8. How often is the trust audited, and do the auditors have access to the vault to physically count the gold?

Agreements among the Trustee, Bank of New York and the Custodian, HSBC USA, NA allow for the Trustees to visit and inspect the Trust’s holdings of gold held by the custodian twice a year. In addition, The Trust’s independent auditors may audit the Gold holdings in the vault as part of their audit of the Financial Statements of the Trust.

But the accountants have not, so far as we can tell from the filings, actually used this right of access to perform a physical count of the bars in storage. This is puzzling. As you can see from the sales of gold reflected in our model, there is plenty of money available for a physical count, and having one in hand would seem to be well worth the cost. For one thing, it would silence the critics of the custody arrangements. For another, it would remove any possible concerns investors might have in connection with the bar quality issue that has recently arisen in the case of the Bank of England, of which more later. So why has it not been done; or, if it has been done, why is that fact not proudly proclaimed?

As noted, we are inclined to give the Trust the benefit of the doubt on the matter of the existence and quality of the gold, even though they don’t make it easy. A bigger concern for us is whether, even assuming it’s all there now, the gold will be there for us when we need it. There are several facets to this concern.

Certificates? We Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Certificates!

In our model, the claim checks that get issued in exchange for the gold deposited at the warehouse are really just one: a global certificate. This certificate, which relates to all the gold held in the Trust, is held by a giant clearing entity known as Depository Trust Company (“DTC”).[6] All interests in the Trust, reflected in Shares, derive from this original claim check. They consist exclusively in entries in the computer databases maintained by a series of financial institutions, starting with members of DTC. The system is summarized as follows in the current (July 24) Prospectus:

Individual certificates will not be issued for the Shares. Instead, global certificates are deposited by the Trustee with DTC and registered in the name of Cede & Co., as nominee for DTC. The global certificates evidence all of the Shares outstanding at any time. Under the Trust Indenture, Shareholders are limited to: (1) DTC Participants, such as banks, brokers, dealers and trust companies; (2) those who maintain, either directly or indirectly, a custodial relationship with a DTC Participant, or Indirect Participants; and (3) those banks, brokers, dealers, trust companies and others who hold interests in the Shares through DTC Participants or Indirect Participants. The Shares are only transferable through the book-entry system of DTC.

The Annual Report, in its summary of the Trust Indenture, goes into a little more detail on what we see as a critical point:

Owners [“Ownership,” in the original Prospectus] of beneficial interests in the Shares is [sic] shown on, and the transfer of ownership is effected only through, records maintained by DTC (with respect to DTC Participants), the records of DTC Participants (with respect to Indirect Participants), and the records of Indirect Participants (with respect to Shareholders that are not DTC Participants or Indirect Participants).

In other words, if you buy a Share, your proof of ownership depends on the continued proper functioning of a series of electronic databases running up to the global certificate. That’s a pretty long supply line in a Russian winter. Granted, this degree of attenuation is not a big deal in the context of normally functioning markets. And it is basically the same system that applies to any other investment you elect to hold in street name with your broker. But the point is that with the Shares there’s no election, no opting out. We worry about our ability to evidence ownership of Shares in the chaotic conditions of a major meltdown, if one or more relevant dominoes should become subject to the tender mercies of a government bailout agency. As the riveting footage from the Northern Rock disaster shows, even in sophisticated markets in today’s digital world, people like to have tangible representations of their holdings in a time of crisis. There is a plausible underpinning to this preference in the securities context: if you want to sell something, experience teaches that you can do so more quickly and easily if you don’t first have to establish your ownership of the item in question to the satisfaction of an overworked and very likely poorly motivated government employee.

The reason the book entry system was adopted seems obvious: it avoids the hassle and cost associated with the physical movement of securities certificates. We don’t dispute the soundness of the call from the standpoint of administrative convenience, although it is not clear why this point could not have been addressed by simply charging fees for the issuance of certificates. But it does bother us to consider that at least some of the purchasers of this instrument will be buying it precisely because they are worried at some level about the possibility of a system failure in which they can always count on good old GLD. If a catastrophic storm does hit, the sad irony is such investors are probably the ones least likely to get out in time.

Members Only

An American reader of the original GLD Prospectus (an impossible construction if ever there were one, since nobody, outside a handful of junior lawyers, ever reads a prospectus in America until a loss is incurred and/or a lawsuit filed) might be puzzled to find the following language in the Risk Factors section:

There are expected to be no written contractual arrangements between subcustodians that hold the Trust’s gold and the Trustee or the Custodian, because traditionally such arrangements are based on the LBMAs rules and on the customs and practices of the London bullion market. In the event of a legal dispute with respect to or arising from such arrangements, it may be difficult to define such customs and practices. The LBMAs rules may be subject to change outside the control of the Trust. Under English law, neither the Trustee, nor the Custodian would have a supportable breach of contract claim against a subcustodian for losses relating to the safekeeping of gold.

What the Dickens, our diligent but imaginary reader might wonder, is this London Bullion Market Association, whose rules — English rules, no less — are law in relation to the GLD money warehouse? If he were to dig a little deeper and actually look up the rules referenced in the Prospectus — a self-regulatory code of conduct with the unlikely name “Non-Investment Products Code” (“NIPs Code”) –, he might reasonably conclude that the LBMA is something of a London gentlemen’s club, because those rules strike the American eye as rather quaint. Reading them, he might well picture a venerable facility wherein members conduct business from antique partners’ desks, or relax in faded leather chairs atop a seedy old Persian rug, an occasional “Good show” or “Not on” scarcely audible above the tinkling of ice in the snifters:

35. Some principals fail to pay due brokerage bills promptly. This is not good practice. Brokerage bills should be paid promptly.

Wrong daydream. While some of the ancient forms and ceremonies survive, principally in the area of self-regulation, the LBMA today is a sprawling congeries of most of the largest financial institutions in the Western world, together with a smattering of colleagues that actually bend the metal, as it were. There is no clubhouse, no squash court, no members’ grill. Delinquent bill payers do not have their names posted on the bulletin board. And while three letters of support from members in good standing are still required in support of an application for membership, to judge from the list of members, it’s money, not breeding, they’re after.

But First, a Little History

As we see it, the principal risks relating to GLD lie outside the instrument itself, in its commercial and juridical contexts. To understand them, it is essential to have some historical background.

The LBMA was established only 20 years ago, as a trade association for the participants in the London Bullion Market (sometimes hereinafter, the Market). But its roots go back to the Seventeenth Century, with the founding in 1671 of the predecessor of Mocatta and Goldsmid, still going strong today as a division of The Bank of Nova Scotia.

The Market historically had two main pillars: the Bank of England, and N.M. Rothschild & Sons. From its very founding in 1694, the Bank of England has been a major factor in the Market, both as principal and as regulator. Its Bullion Office received, weighed and stored imports of gold until well into the Nineteenth Century, when, as a result of the increased flow of gold from the gold rushes in California and Australia, private brokers began to weigh and store gold independently of the Bank. Today, the Bank continues as an active Market participant. Beyond holding, storing and lending out the UKs official gold reserves, the Bank provides commercial services to clients who include not only central banks but also private commercial firms. These services importantly include custody or vaulting services: in its Annual Report 2007 the Bank reported holding £43 billion in gold as custodian, equal to approximately 4,000 tonnes.[7] They also include bullion banking: the Bank accepts gold deposits from other central banks, and lends these out into the Market for a spread.[8] In addition to its commercial activities, the Bank still has a modest regulatory role in the Market, providing general oversight and “facilitating” the NIPs Code we encountered earlier.

The second historic pillar of the Market, the storied London branch of the Rothschild banking dynasty, was a relative latecomer to the Market. Nathan Mayer Rothschild, lately of the textiles and smuggling trade, announced only in July 1811

that the business heretofore carried on by the undersigned Nathan Meyer [sic] Rothschild at Manchester, under the firm of Rothschild Brothers’ will cease to be carried on from this day, and any persons having dealings with that firm are required to send their demands to pay their accounts to N.M. Rothschild, at his Counting-House, in No. 2 New Court, St Swithins-lane [sic], London.[9]

Rothschild made up for lost time, though, by seizing the opportunity to finance the Peninsular campaign against Napoleon with smuggled shipments of bullion.

When I was settled in London, the East India Company had £800,000 worth of gold to sell. I went to the sale, and bought it all. I knew the Duke of Wellington must have it. I had bought a great many of his bills at a discount. The Government sent for me and said they must have it. When they got it, they did not know how to get it to Portugal. I undertook all that and I sent it to France; and that was the best business I ever did.[10]

Rothschild established a direct relationship with the Bank of England in 1823, finally disintermediating his old rivals Mocatta and Goldsmid, until then the Banks designated bullion broker. In 1825 he rescued the Bank by delivering sufficient gold to enable it to avoid suspension of exchange. Indeed, almost from Rothschilds arrival in London, no other firm has been more intimately involved with either the Bank of England or the London Bullion Market.

Over time, the Market became critically important to the power and influence of the City of London. It may be only a slight exaggeration to maintain that the history of the Market is the history of the City of London, and that the history of the City is the financial history of the British Empire. The presence of the physical gold market in London was essential to Londons standing as the leading financial center of the world. The flow of fresh supplies of gold to London, rather than to other financial centers, gave the Bank of England a considerable cost advantage, and underlay its success in operating the gold standard:

For well over a century, the ability of the City of London to stand as the center of international finance had depended on its controlling the physical trade of gold through London. The world economy in the 19th Century rose or fell, as the supply of such gold to London bullion banks such as Rothschild’s & Sons, rose or fell.[11]

Commerce Interruptus

The Twentieth Century was hard on the Market. The Market was closed for business for more than 20 years as a result of three separate interruptions of varying lengths. The first was occasioned by the outbreak of World War I, and lasted five years, from August 1914 through September 1919. The Great War marked the end of the gold standard and the beginning of the series of half-baked monetary expedients that led in a more or less straight line to today’s pending debacle. The War transformed the Market as well; upon reopening, the Market took a recognizably modern form.

At that time there was grave concern on the part of the London Establishment that New York would displace London as the center of world finance. The immediate risk was that South Africa might ship its future gold mine production directly to New York, as the United States was in a position to return to the gold standard promptly after a suspension of only two years, whereas England, devastated by the War, was not. An organization called the London Gold Producers Committee, which controlled the minting of imported gold, wrote the Governor of the Bank of England in March 1919:

If the stream of gold from South Africa is once diverted to New York, it will not be so easy later to turn it back again, as, if New York becomes the best and freest market for bullion, it will be a powerful influence in establishing New York as the central money market of the world.[12]

This ghastly outcome was averted by means of some Imperial hardball, as a result of which

Contracts were entered into between the gold mines and the Bank of England, and between the gold mines and Messrs. N. M. Rothschild & Sons, who were appointed London agents of the gold mines for the sale of gold. Under the terms of these contracts the members of the Transvaal Chamber of Mines shipped all gold produced, except a small amount retained in South Africa for currency needs, to the Bank of England…[13]

Rothschild sold the gold on the Market after it was refined. The bidding opened on September 12, 1919, when the first gold Fixing occurred. The Fixing was soon formalized in a ceremony conducted daily at Rothschild’s office, in which deputies representing five of the largest Market participants would raise and lower miniature flags on their desks to signify completion or continuing dialogue on a proposed price.

The second closure of the Market was occasioned by the outbreak of World War II, and lasted fifteen years.[14] The Market was closed in September 1939, and reopened on March 22, 1954. When it was reopened, London had managed to retain control over the South African gold trade, and the Fixing was still quoted in sterling, but the purpose now was to support the international monetary system embodied in the Bretton Woods agreements, i.e., to keep the price per ounce equivalent to $35. These arrangements lasted only 14 years, until the third market closure occurred. This closure, the shortest of the three in elapsed time, but perhaps the most significant in relation to GLD, was occasioned by the collapse of the London Gold Pool.

A Little More History: Gold Pool I

The story of the London Gold Pool is well known to gold bugs, but because its unraveling has important implications with respect to GLD, we’ll rehash a bit of it here. The Gold Pool (let’s call it “Gold Pool I”, just to distinguish it from the contemporary price management scheme alleged by Citigroup, which we’ll call “Gold Pool II”) was borne of budgetary and trade imbalances of the United States during the 1950’s and 1960’s. Try as the US authorities might, it proved increasingly difficult to persuade foreign holders of dollars not to exchange them for their gold backing.

Nothing sufficed. The accumulation of productive and profitable foreign assets by American firms and investors seemed to count for little. The U.S. gold stock declined every year from 1958 to 1971, falling from $19 billion to $10 billion, while America’s liquid liabilities to foreigners rose every year over the same period of time until they had expanded to over $60 billion. As the French economist Jacques Rueff put it on October 20, 1967, when the gold stock was $12 billion and the liabilities were $33 billion, the United States had exhausted its ability to pay off its creditors in gold: “It is like telling a bald man to comb his hair. There isn’t any.” [15]

Addressing the underlying problems was, of course, out of the question, so the monetary authorities set about manipulating the market price of gold instead. Starting in 1961, the United States, taking half the Pool itself, led the United Kingdom, France, West Germany, France, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands in a flamboyant waste of public assets so grand, so misconceived, so futile, as to make Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown’s decision to dump half the UK’s gold reserves at the bottom of the market some 30 years later look positively brilliant by comparison.

What the London Gold Pool heroically set out to do, under the leadership of the United States with the Europeans glumly in tow, was to keep the gold price at $35/oz. by dumping gold onto the free market. Why $35 /oz. no one bothered to explain. Why not $30, or $40, or even $50 an ounce. We dont know. The official price was $35 an ounce and apparently the Treasury believed, somewhat like King Canute, that if a Treasury edict would not stop the tide in the English Channel, at least it could most certainly establish a price for a barbaric relic like gold.[16]

The Bank of England, in view of its knowledge in the ways of gold, was the logical choice to be named operator of the Pool, and the daily Fixing, in view of its central role in price discovery, was the logical choice for the conduit. After an early honeymoon phase, Gold Pool I had to pour official gold into the Market for no fewer than seven years.

At the beginning, with new production coming in large quantities into London, the pool was able to buy more gold at $35 than it had to sell. The struggle with the speculators became increasingly one-sided, however, after General de Gaulle started beating the drums for an increase in the price of gold. In fact, General de Gaulle had pulled France out of the gold pool during 1967. In early March 1968, the United States had to transfer $950 million in gold to London to keep the price close to $35; nearly $2.5 billion had been paid out from Fort Knox since November 18, 1967, when the British had devalued sterling for the second time since the end of World War II.[17]

On March 14, 1968, Gold Pool I lost a stunning 400 tonnes of gold. The next day, H.M. Treasury issued the following statement[18]:

The London Gold Market will be closed today, Friday, March 15. This is at the request of the United States Government.

At a meeting of the Privy Council held this morning at Buckingham Palace, Her Majesty the Queen approved a proclamation appointing Friday, 15th March, to be observed as a Bank Holiday throughout the United Kingdom.

The banks are, however, being asked to provide their domestic customers with normal cash requirements in sterling.

The authorities are requesting that the stock exchanges also be closed.

On the following Monday, the Bank of England formalized the closure of the Market for a period of two weeks. [19]

Notice to Authorised Dealers in Gold

Exchange Control Act of 1947

The Bank of England have been instructed by H. M. Treasury to exercise certain powers delegated to them by H. M. Treasury under Section 37 of the Exchange Control Act [of] 1947.

In exercise of the powers conferred upon H. M. Treasury by Section 34(2) of that Act and delegated as aforesaid, the Bank of England hereby direct Authorised Dealers in Gold not to buy or borrow or to sell or lend any gold bullion until the opening of business on Monday, the 1st April 1968.

The Market duly reopened on April 1. But it was a different market. Although it had only been following orders in implementing this absurd attempt to repeal the laws of economics, London was the big loser. The price would henceforward be quoted in dollars, not sterling.[20] A second, afternoon fixing, was added for the convenience of the New York futures market. Worse, the South Africans had taken their business elsewhere, to Zurich, during the two week closure. London was no longer the dominant force in gold distribution.

Dawn of a New Era

If the Twentieth Century was hard on the Market, the Twenty-first bids fair to be even harder. A series of developments in 2004, in particular, gave warning of disquiet in the realm.

What Do They Know?

On April 14, the Market was rocked by the following announcement:

N M Rothschild & Sons Limited, London announces that it is withdrawing from commodities trading, including gold.

The decision has been taken following a strategic review of the services offered by Rothschild and will result in the withdrawal from commodities sales and trading activities in London.

As part of this decision, Rothschild will be withdrawing from the twice daily London Gold Fixing which it currently chairs. Discussions are being held with other members of the Fixing to ensure an orderly handover of the Chairmanship.

It was as if — and here once again we betray our bias — the Boston Red Sox had announced their withdrawal from the game of baseball.

The gold world didn’t know quite what to make of the Rothschild exit. Although there was a fair degree of consensus that it was likely, just as Rothschild said, about money, there were differing emphases. Some on the fringe quietly speculated the move might signify a recognition by Rothschild that (a) the Market was under severe stress, i.e., that Gold Pool II was about to blow up; (b) the blowup would create a huge opportunity to make money as principal; (c) there is downside in trading against your clients in such a scenario, particularly when your clients include central banks; and (d) there is downside to being linked with a spectacular failure. See, e.g., Hard Money Markets: Climbing a Chinese Wall of Worry (RHH).

The London Establishment, now a different animal after many decades of Keynesian indoctrination, saw things somewhat differently.[21] Its champion, the Financial Times, was quick to speculate that Rothschild’s departure merely betokened yet another reason to dance on gold’s grave. In a typically measured and thoughtful editorial run two days after Rothschild’s announcement, the FT cackled:

Going, Going, Gold

The barbarous relic, as Keynes called it, is crumbling to dust. When even the venerable N.M. Rothschild has quit the gold market and the Bank of France, among the most stubborn of the official goldbugs, is thinking again about its bullion holdings, the end of gold as an investment has come a little closer. It will not be before time. The fetishisation of shiny yellow metal, decades after it ceased to be used as the anchor of the international monetary system, is a lingering anomaly in modern financial markets. Perhaps Rothschild’s last service to the bullion market could be to keep a live gold trader on display behind glass as a reminder of a bygone age, like the former coal miners who now make a living giving tours of defunct pits.[22]

Less than two months later, there was another prominent defection. AIG International Ltd., which had previously played the major role in silver dealing, withdrew as a market maker for both gold and silver.

Guess Who’s Coming to Lunch

Several days after AIG pulled out, the Deputy Chairman of the Bank of Russia suddenly started speaking in tongues from the podium of an LBMA conference in Moscow. Anticipating Citigroup’s conspiracy theory by three full years, Hon. Oleg V. Mozhaiskov observed, in an address entitled Perspectives on Gold: Central Bank Viewpoint:

This dualism in gold price formation distinguishes it from other commodities and makes the movements in the price sometimes so enigmatic that market analysts need to invent fantastic intrigues to explain price dynamics. Many have heard of the group of economists who came together in the society known as the Gold Anti-Trust Action Committee and started a number of lawsuits against the U.S. government, accusing it of organising an anti-gold conspiracy. They believe that with the assistance of a number of major financial institutions (they mention in particular the Bank for International Settlements, J.P. Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, and others), some senior officials have been manipulating the market since 1994. As a result, the price dropped below US$300 an ounce at a time when it should, if it had kept pace with inflation, reached US$740-760.

I prefer not to comment on this information but dare assume that the specific facts included in the lawsuits might have given ground to suspicion that the real forces acting on the gold market are far from those of classic textbooks that explain to students how prices are born in a free market.

Five months later, as if 2004 had not been quite eventful enough in the London Bullion Market, GLD was launched.

Back to the Present: the Market and the LBMA

Today, the London Bullion Market is not a London market at all, but a global over the counter market trading on a 24-hour per day continuous basis, conducted principal to principal, and principal to client, over the telephone and through electronic dealing platforms. It has no formal structure and no open-outcry meeting place. Nor is it a bullion market exclusively. Market players create and trade forwards, options and other derivatives as well. Because it is both deep and opaque, it is the venue of choice for trading gold among central banks. It is also the conduit through which some countries lend out their official gold reserves through deposits made with the Bank of England or other bullion banks.

The LBMA is the trade association that represents the participants in this global wholesale market. Despite its name, its members are no longer required to be domiciled in England. Its membership currently consists of 113 entities organized in three tiers: 10 Market Making Members, each a giant bank obligated to make two-way prices (that is, for both buying and selling) throughout the day; 56 ordinary Members, mostly financial institutions, which typically quote prices to their own clients, but have no obligation to make two-way markets or to quote to other dealers; and 47 Associates, mostly refiners. Six of the Market Making Members provide the clearing function for transactions in paper as well as physical gold; although the market for physical gold is distributed globally, most OTC market trades are understood still to be cleared through London. Five of the Market Making Members still get together twice daily to perform the gold fixing, but sadly, since Rothschild’s departure, they do so by telephone rather than in person, and without the miniature flags.[23]

Maintaining the Grade

Of the several functions of the LBMA, perhaps the most important relate to setting refining and delivery standards. It maintains lists, known as the “London Good Delivery Lists”, of accredited melters and assayers of gold, and sets standards, known as “The Good Delivery Rules for Gold and Silver Bars” for the weight, dimensions, purity and identifying marks of the units of gold traded in the Market.

These standards, or rather, their existence, recently broke into the mainstream press. The story began well over a year ago, with the announcement by the LBMA on June 9, 2006 that a lot of bad metal had been showing up in the Market:

LBMA Good Delivery List for Gold and Silver

Treatment of Bars from Deep Storage [24]The LBMA has noted that in the past year, an increasing number of gold and silver bars have been re-appearing in the market after having been held for many years in vaults (whether in London or elsewhere). Most of these bars will still be acceptable in the London bullion market, even if they are not fully compliant with the LBMAs current Good Delivery Rules, which have been modified in a number of ways since the establishment of the LBMA in 1987.

However, some of these deep storage bars may no longer be regarded as acceptable, either because of physical defects or poor marking. This can apply both to bars from currently active Good Delivery List refiners and also to those from refiners which are now on the Former List (and which may well no longer be in business). In particular, the LBMA has confirmed that bars which are not stamped with the original refiner’s assay mark and fineness (with these being shown instead on an accompanying certificate) will no longer be acceptable as Good Delivery.

On September 29, 2007, The Times of London fingered the Bank of England as a prime culprit in the deep storage standards imbroglio, reporting on a story first broken by Metal Bulletin:

All that glisters may not be gold

Hidden away in vaults under the City of London, Britain’s hoard of gold bullion, regarded as the best insurance against any turmoil in global money markets, is beginning to crumble. The deterioration, some experts claim, may suggest that it is not pure gold.

The Bank of England, guardian of the 320-tonne stash under Threadneedle Street, admitted yesterday that cracks and fissures had appeared in some of its gold.

* * * * *

Revelations about its physical deterioration were secured by the trade journal Metal Bulletin, which has been trying to ascertain the truth since May. Rumours that the Bank’s gold was not in tiptop condition have circulated in the gold market for years, but Stuart Allen, the Bank’s deputy secretary, has now confirmed there is an issue.

To be traded, gold bars have to meet so-called London Good Delivery (LGD) standards, as laid down by the London Bullion Market Association. Mr Allen wrote to the journal: “There is some uncertainty about the status of LGD standards in respect of certain categories of gold bars that have been held in deep storage for many years.”

The Bank was in discussions with the association to clarify how much of its gold was in sub-standard condition, Mr Allen added.

To the quiet denizens of the gold world, this was Britney, JLo and OJ all in one. Of the many questions that jump to the inquiring mind, here is just a sampling.

1. What is the Bank of England doing in this thing? Gold is ductile, and doesn’t crack or frizzle. That’s one of the features that make it permanent, natural money. The Bank of England has been an active participant in the London Bullion Market, as well as its self-regulatory den mother, for over three hundred years. It practically designed the standards, along with all the other rules. So we are to understand that it, of all players, is now offside?

2. Whose gold are they talking about? As we have seen, the Bank of England claims to hold a lot of gold for third parties. The remaining British reserves in its vaults account for less than 10% of the approximately 4,000 tonnes reportedly held as custodial gold. So of all the gold the Bank holds, it has, just lately, detected a problem with a portion of the 320 tonnes held for H.M. Treasury?

3. Why is this issue surfacing now? How would a deficiency in standards of gold stored quietly away — in deep storage, no less — get noticed in the first place? What sorts of transactions have been under way, over what timeframe, and in what quantities, that the Bank of England would be down to sticks and stems, and be unable simply to handle the matter quickly and quietly? How is it possible that this problem could be so intractable as to force its way into the mainstream press after well over a year of irresolution?

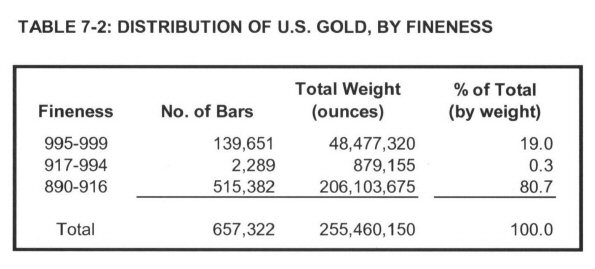

4. Is there an American connection? In the Bank of England press coverage, the references to cracks could reflect misdirection, misunderstanding, or an imprecise form of shorthand for problems with the fineness. That is, the real problem could be that the bars have a higher base metal content than the standards allow. This problem could arise if the bars were cast from melted coins, as coins have higher base metal content than good delivery bars. This in turn would raise the question of whether the United States was the source of the bars in question. That’s because the bulk of the US bullion holdings consists of coin melt, bars made from coins melted down after the Roosevelt Administration’s seizure of circulating gold coinage in 1934. Only about 20% of US bullion is understood to meet London Good Delivery standards.[25] The possibility of an American connection is of particular interest in view of the Bank’s and the LBMA’s curious use of the term “deep storage”, first introduced by American authorities six years ago to refer to gold held by the US Treasury (see Note 24). So: did any of the offending metal come from the United States? If so, when, and under what circumstances?

We don’t know the answers to any of these questions. We probably never will. But we are inclined to think that the nucleus of fact that underlies them signals yet more stress in the Market. All we need is a blistering editorial from the FT to be sure.

Publishing Clearing Volumes

Another function served by the LBMA relates to record keeping. The LBMA does not publish any comprehensive data on the quantity of gold held in the vaults of its members, or traded in the Market. Nor does anyone else; it is manifestly not in the interest of the central banks to have such information in the public domain. Accordingly, the gold world was stunned in January 1997 when the LBMA began to publish statistics relating to daily clearing of gold transactions. As clearing rather than turnover statistics, the volumes indicate net amounts of gold transferred on the books of the Clearing Members. The actual trading volumes are undisclosed, but, according to the LBMA, have been estimated to be a positive multiple of the clearing volumes with a multiplier of between 5 and 9.[26] It was not clear why the LBMA chose to release these figures. Some speculated at the time that it was a bid to attract investor interest, or an attempt to put the announced sales by central banks into proper perspective. What was clear was that the daily volume of transactions in gold was — and remains — huge in relation to annual mine output and even in relation to estimated above ground stocks. They suggested, indeed, that the Market is effectively a shadow money market for a stateless currency. For example, in August 2007 the average daily clearing volume was 18.2 million ounces; at a multiplier of 5, that indicated daily turnover of 91 million ounces (2.8 thousand tonnes), as against estimated above ground stocks of approximately 160 thousand tonnes, and annual mine production of approximately 2.5 thousand tonnes.

Backstopping a Public Offering of Securities in the United States

But the LBMA’s oddest function by far is its role as the beating heart of GLD. As the Prospectus makes abundantly clear, the only people who can deposit or withdraw gold at the warehouse are so-called “Authorized Participants”:

Baskets may be created or redeemed only by Authorized Participants. Each Authorized Participant must (1) be a registered broker-dealer or other securities market participant such as a bank or other financial institution which is not required to register as a broker-dealer to engage in securities transactions, (2) be a participant in The Depository Trust Company or DTC Participant, (3) have entered into an agreement with the Trustee and the Sponsor, or the Participant Agreement, and (4) have established an unallocated gold account with the Custodian, or the Authorized Participant Unallocated Account.

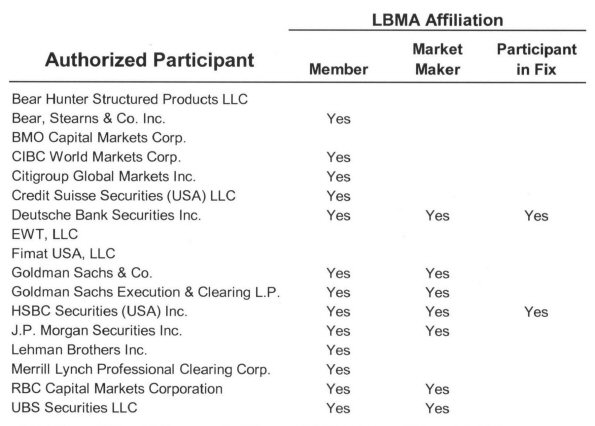

As of June 30, 2007, the Authorized Participants were as follows:

Thus with the exception of Bear Hunter, which has been the NYSE Specialist for GLD since inception, and the mysterious EWT and Fimat, each of the Authorized Participants is a household name global financial institution, and, with the further exception of BMO, each is an affiliate of a Member of the LBMA. Six (treating the two Goldman Sachs entities as one) are affiliates of the 10 Market Making Members, and two are participants in the Fixing.

Loco London

The initial GLD Prospectus contained the following statement:

The term “loco London” gold refers to gold physically held in London that meets the specifications for weight, dimensions, fineness (or purity), identifying marks (including the assay stamp of a LBMA acceptable refiner) and appearance set forth in “The Good Delivery Rules for Gold and Silver Bars” published by the LBMA. [Emphasis supplied.]

This is a curious statement. It implies that for gold to satisfy good delivery requirements, it must be held in London. This is not correct. Since, as noted above, the OTC market is global, no longer London based, the delivery standards are not location specific. Loco London, at least according to the LBMA, is a settlement term: “[t]his term means that the gold or silver will be settled in London either by way of book transfer or physically.” [27] [Emphasis supplied.] It is not a custody term.

Nevertheless, as the FAQs make clear, GLD'[s gold is held in London.

3. Where is the gold held? Is it safe?

The gold that underlies Gold Shares is held in the form of allocated 400 oz. London Good Delivery Bars in the London vaults of HSBC Bank USA. The safekeeping methods are essentially no different from those that have operated without a problem in the London market for centuries. Those safeguards have stood the test of time for both individuals and institutions (including many governments) that store their gold in London vaults. We have tremendous confidence in the Custodian’s efforts to ensure the safety of the Trust’s gold bullion.

But why? It could as easily be held in New York, where, after all, its owner, the Trust, is located, and where the securities issued against it are traded. Or better yet, it could be located in Zurich, which is, after all, the financial capital of the country where the Sponsor’s parent, the World Gold Council, is domiciled. Unlike the United States, Switzerland has never confiscated its citizens gold; unlike the United Kingdom, Switzerland has never closed its private bullion market. Each of the three cities is a hub of the Market, according to the Prospectus. So why London?

We are left to speculate. Perhaps it was the Bank of England defending its turf again. Or perhaps it was simply a matter of administrative convenience or cost containment; the documentation was already complicated enough, so why layer in another complication with a location swap or a pricing adjustment. Or maybe it was to take advantage of a regulatory framework generated by the players rather than the regulators: although the giant financial institutions that comprise the LBMA are extensively regulated in their main business lines, in the case of gold, London offers a quiet haven where the women cease from troubling and the wicked are at rest.

Whatever the reason behind the original selection of London as the situs for GLD’s gold, that choice has troubling implications today.

The City as a Risk Factor

We have a theory. Or rather, Citigroup has a theory, and we embrace it: the gold price management conspiracy among central banks — “Gold Pool II” — is, for all practical purposes, over.

But withdrawals from such ill-considered engagements can be messy for those left behind. Short positions will have been taken, exposures increased, risks run by loyal retainers left in country. The physical gold market is, by hypothesis, in a state of disequilibrium: there is an excess of demand over supply, as the market clearing price has been throttled in favor of an artificially maintained and undisclosed official peg over a period of years. This disequilibrium must be resolved. The resolution, if left to itself, could be disorderly, potentially posing grave risk to some very large banks, and fatally undermining confidence in fiat currencies. The question arises, will the affected governments suddenly forswear intervention and allow the market to sort itself out, or will they succumb to the irresistible temptation to lend a stabilizing hand? The question answers itself.

Recent developments suggest that such efforts, if undertaken by the British authorities under whose jurisdiction GLD’s gold now resides, would not be without their awkward moments.

We begin with the change in leadership that took place one week to the day after the Bear, Stearns fiasco: Gordon Brown became Prime Minister. Whatever else may be said of Mr. Brown, during his tenure as Chancellor of the Exchequer he did not distinguish himself as The Best Friend of the Gold Market. Indeed, gold bugs will recall that Mr. Brown repeatedly and noisily agitated in favor of a sale of IMF gold, ostensibly for the purpose of benefiting heavily indebted countries.[28] They will also recall Mr. Brown’s response, when thwarted in that enterprise: he turned his guns on his own nation’s gold reserves. The infamous sale of half the British public’s gold was recently recounted by The Sunday Times:

Goldfinger Brown’s £2 billion blunder in the bullion market

Gathered around a table in one of the Bank of England’s grand meeting rooms, the select group of Britain’s top gold traders could not believe what they were being told.

Gordon Brown had decided to sell off more than half of the country’s centuries-old gold reserves and the chancellor was intending to announce his plan later that day.

It was May 1999 and the gold price had stagnated for much of the decade. The traders present including senior executives from at least two big investment banks – warned that Brown, who was not at the meeting, could barely have chosen a worse moment.

* * * * *

A trawl of experts and dealers in the market by The Sunday Times has been unable to find anyone who was approached by the Treasury to outline the long-term prospects for gold. The London Bullion Market Association said it was unaware of any such advice being sought from its members.

It is therefore not known on what expert basis the decision to sell such a large amount in a relatively short period was taken.

Brown offloaded the gold at a 20-year low in the market now nicknamed the Brown bottom by dealers. The 17 auctions achieved prices for the gold of between $256 and $296 an ounce, with an average of $275. Since then gold has risen sharply in value and stood yesterday at $685. This year, some top investment banks have predicted, it could even rise above the all-time high of $850.

Less well known is Mr. Browns role as the architect of the UK financial regulatory reorganization of 1997. This important restructuring established the current system under which, among other reforms, the Bank of England has become largely an order taker in regulatory matters. The net result of Mr. Browns reorganization, when put to the test in the Northern Rock crisis, was bumbling incoherence. A leader in the September 20th edition of The Economist was unsparing in its criticism:

No sooner had the queues disappeared than the inquest began. This was the first big test of Britain’s monetary and regulatory arrangements since Gordon Brown shook them up within days of arriving at the Treasury in 1997. The Bank of England was given operational independence to set interest rates, but it was stripped of its job as the banking supervisor…

Until this summer, Mr Brown’s reforms seemed to be working well. The Bank of England was lauded for keeping inflation close to the government’s target and ensuring a steady expansion of the economy. The FSA won praise for its deft touch, especially in regulating complex financial businesses, which helped bolster the Citys appeal as an international centre. But in just a few days a financial storm has blown a hole in the hard-won reputations of the regulator and the central bank. Mr Brown’s new system of split responsibility has failed its first big regulatory test.

* * * * *

This debacle holds lessons for the way Britain regulates its banks. … Mr King defended the separation of powers between the Treasury, the Bank and the FSA, but he was wrong to. It has exacerbated the system’s flaws: nobody was in charge of the operation.

The Northern Rock drama was an opera bouffe. One day, the Bank of England was talking tough about moral hazard. The next day, it was caving under pressure from the government. One day, the Treasury was guaranteeing all deposits in a panic, essentially nationalizing the entire banking system through the back door. The next day, it was reneging under pressure from the banks and the insurers. Virtually all important actions of officials were ad hoc and unprincipled. The situation today remains fluid, and lacks clarity.

Certain things are perfectly clear, however: (a) there is ample precedent for closure of the London Bullion Market in a crisis; (b) the Market continues to show signs of stress; (c) the UK government is no friend of the Market; and (d) the UK financial regulatory apparatus is in a state of disarray.

Come and Get Us

Let’s run some scenarios. But first, consider the following provisions of the Custody Agreement (again, “we” is the Custodian, “you” is the Trustee; emphasis supplied):

4.4 PHYSICAL WITHDRAWALS OF BULLION: Anything in this agreement to the contrary notwithstanding, and without limiting your right to withdraw Bullion physically, we shall not be obliged to effect any requested delivery if, in our reasonable opinion, this would cause us or our agents to be in breach of the [NIPs Code] or other applicable law, court order or regulation, the costs incurred would be excessive or delivery is impracticable for any reason .12.1 EXCLUSION OF LIABILITY. We will use reasonable care in the performance of our duties under this agreement and will only be responsible to you for any loss or damage suffered by you as a direct result of any negligence, fraud or willful default on our part in the performance of our duties, in which case our liability will not exceed the market value of the Bullion at the time such negligence, fraud or willful default is discovered by us, provided that we notify you promptly after we discover such negligence, fraud or willful default…

12.4 FORCE MAJEURE. We shall not be liable to you for any delay in performance, or for the non-performance of any of our obligations under this agreement by reason of any cause beyond our reasonable control. This includes any act of God or war or terrorism, any breakdown, malfunction or failure of transmission in connection with or other unavailability of any wire, communication or computer facilities, any transport, port, or airport disruption, industrial action, acts and regulations and rules of any governmental or supra national bodies or authorities or regulatory or self-regulatory organisations or failure of any such body, authority, or organization for any reason, to perform its obligations.

It’s Thursday evening, and you are long GLD. The afternoon Fix in London was $1,100; GLD closed in New York at $100. Work out your recovery in each of the following hypothetical scenarios. How much will you get for your GLD book entries? Denominated in what currency? When will you get your payment?

Scenario 1. On Friday, H.M. Treasury proclaims a bank holiday in the United Kingdom. On Monday, the Market is closed until further notice. The LBMA, alarmed at reports of crippling losses to Members arising from the Market turmoil, adopts a series of amendments to the NIPs Code. The amendments provide, among other things, for cash settlement of contracts entered into prior to the date of the Market closure. When the Market reopens some weeks later, gold bullion is priced in euros, and trades at a multiple of the last Fixing price.

Scenario 2. On Friday, H.M. Treasury, acting at the request of the US Government, orders the cessation until further notice of all transactions involving Strategic Commodities Held Offshore by US Persons, as such terms are defined in the US Financial Strength and Prosperity Act (the “USA Prosperity Act”). Subsequent directives provide that holders of SCHOs are to be compensated by the US Government at fair market value as of the effective date of the USA Prosperity Act, upon satisfactory proof of claim.

Stumped? Don’t feel bad. Those are trick questions. It will take squads of lawyers and solicitors the better part of a decade to sort all this out. Jarndyce v. Jarndyce meets Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino.

Our scenarios are by no means exhaustive. But they illustrate the situational risk. Recall that the quantity of gold now amassed in the Custodian’s vaults exceeds the amount reportedly held as national monetary reserves by all but 10 central banks. To paraphrase the noted philosopher and bank robber Willie Sutton, the acquisitive mind is naturally drawn to where the money is. In 1934, the money was in the United States, within the banking system. So that’s where the confiscation of private gold occurred. Today, the money is in London, deep within the Realms of GLD.

The Moral of the Story

So what are we to think about all this? Well, that depends on who we are.

If we are the World Gold Council, we might consider moving GLDs gold to a safer neighborhood. Failing that, we might consider beefing up those risk factors in the Prospectus.

If we are an institutional fiduciary, we might consider testing the exchange feature to make sure we can access our gold. Once we get it, if we get it, we might consider hanging on to it. Otherwise, we might want to ring up Legal and inquire as to our exposure if the GLD gold is blocked or seized.

If we are an institutional principal, it’s our money, we’ll do what we want.

If we are an individual investor, we might just ask ourselves: Why are we here?

October 15, 2007

DISCLAIMER & CONFLICTS

THE FOREGOING ESSAY IS FOR YOUR INFORMATION AND AMUSEMENT ONLY. NEITHER MR. LANDIS NOR GOLDEN SEXTANT ADVISORS LLC (GOLDEN SEXTANT) IS SOLICITING ANY ACTION BASED UPON IT, NOR IS EITHER MR. LANDIS OR GOLDEN SEXTANT SUGGESTING THAT IT REPRESENTS, UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES, A RECOMMENDATION TO BUY OR SELL ANY SECURITY. THE CONTENT OF THE ESSAY IS DERIVED FROM INFORMATION AND SOURCES BELIEVED TO BE RELIABLE, BUT NEITHER MR. LANDIS NOR GOLDEN SEXTANT MAKES ANY REPRESENTATION THAT IT IS EITHER COMPLETE OR ERROR-FREE, AND IT SHOULD NOT BE RELIED ON AS SUCH. MR. LANDIS AND GOLDEN SEXTANT AND ENTITIES UNDER THEIR RESPECTIVE CONTROL MAY HAVE INVESTMENT POSITIONS, LONG OR SHORT, IN ANY SECURITIES MENTIONED, AND ANY SUCH POSITIONS MAY BE CHANGED AT ANY TIME FOR ANY REASON.

Notes

1. Montagu Norman, fabled Governor of the Bank of England, described the concept thus:

I do not believe that gold in circulation can safely be regarded as a reserve that can be made available in case of need, and I think that even in times of abundance hoarding is bad, because it weakens the command of the Central Bank over the monetary circulation and hence over the purchasing power of the monetary unit.

For these reasons, I suggest that your best course would be to establish convertibility of notes into gold bars only and in amounts which will ensure that the use of monetary gold can be limited, in case of need, to the settlement of international business.

Melchior Palyi, The Twilight of Gold (Henry Regnery, 1972), p. 121.

2. Unallocated Bullion refers to gold on the way into or out of the warehouse, sitting in a general account of the Custodian. While in this temporary posture, settled daily, it is deemed to be owned by the Custodian, not the Trust, and is therefore subject to the risk of the Custodian’s bankruptcy. Allocated Bullion, on the other hand, refers to gold that has been processed for storage and registered in the name of the Trust, and is not subject to the risk of the Custodian’s bankruptcy.

3. Our friend Tony Deden of Edelweiss Fund in Zurich reports that he recently attempted to exchange some 600,000 Shares through UBS (Switzerland), with whom he has had a longstanding relationship on the brokerage and custody side. It turned out there was little to no connection with the UBS affiliate which is an Authorized Participant. To establish a bullion trading account with the Authorized Participant would have required starting from scratch. There were no standard terms and conditions for such an account, and Tony ultimately concluded that the procedure was “unclear, arbitrary and purposefully complex” so as to deter exchange. Even if he had had the time and patience to run all the traps, the gold was proposed to be delivered to him in Stamford, Connecticut.

4. See, for example, the critiques by James Turk: Where Is the ETF’s Gold?, November 22, 2004; and Securities & Exchange Commission vs World Gold Council, December 8, 2004.

The issue is still live. As recently as October of 2006, one of the Trust’s senior officers had to address it in a broadcast on theStreet.com:

BROADCAST TRANSCRIPT

Date October 12, 2006 Time 01:00 PM – 02:00 PM Station www.thestreet.com Location Network Program TheStreet.com CONSTABLE: And that gets to another question I get frequently: is the gold actually there? I mean quite a lot of gold market investors are risk averse, and the question keeps coming up to me is–well, is the gold in the vaults? So George, I understand you’ve been there. Is the gold there? Mr. STANLEY:Oh, I’ve been there. I’ve smelled it. I’ve touched it and dusted it off. It’s part of the due diligence process that some of our executives go there several times a year. I was there last, I think, in August or September at the vault in London and it was at a time when the inspector at the organization that actually monitors this on our behalf was doing the regular biennial exam–biannual– CONSTABLE: And that’s where they count the gold? Mr. STANLEY: They count the various bars. CONSTABLE: They weigh them. Mr. STANLEY: Yeah, they weigh them. They check the appearance. They make sure they’re all proper good delivery. CONSTABLE: So nothing to worry about there on that front? Mr. STANLEY: Nothing to worry–but there will always be investors who want their own gold in their own hands. GLD is not the vehicle for them.

5. For example, several weeks after GLD was launched, an attentive observer noted 78 duplicate bar numbers out of a total of 6,981 bars on the list. The discrepancy was commented upon by James Turk in More Questions About the ETF’s Gold, December 6, 2004, and was addressed by the posting of an explanatory letter from Johnson Matthey dated December 8, 2004.

6. The SEC describes DTC as follows (footnotes omitted):

The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”), the largest securities depository in the world, provides custody and book-entry transfer services for the vast majority of securities transactions in the U.S. market involving equities, corporate and municipal debt, money market instruments, American depositary receipts, and exchange-traded Funds. In accordance with its rules, DTC accepts deposits of securities from its participants (i.e., broker-dealers and banks), credits those securities to the depositing participants’ accounts, and effects book-entry movements of those securities. The securities deposited with DTC are registered in DTC’s nominee name and are held in fungible bulk for the benefit of its participants and their customers. Each participant having an interest in securities of a given issue credited to its account has a pro rata interest in the securities of that issue held by DTC.

The text is from a notice of adoption of SEC Rule 17Ad-20, prohibiting the attempt by certain issuers of securities to opt out of the depositary system by restricting the transfer of their shares to intermediaries. Those issuers maintained that the depositary structure facilitated naked short selling of their stock.

7. James Turk makes the point that we don’t really know what this £43 billion in custody means, unless we know the accounting convention that governs the disclosure. Under IMF rules, the Bank of England could be referring to gold out on loan. What is more, we can’t really tell from anything in the Annual Report whether the reference is to gold stored in the Bank’s vaults or elsewhere, or even whether the reference is to physical gold.

8. A good account of the role of the Bank of England in the London Bullion Market may be found in a speech given to the LBMA Annual Conference in June 2003.

9. Niall Ferguson, The House of Rothschild (Penguin, 1998), p.59.

10. Id., p. 87. Wellington was facing an acute cash crisis. Ferguson writes: “…as he explained to Earl Bathurst, he was only just able to pay for the subsidies to his allies. In the absence of cash, he was reduced to paying officers in depreciated paper money, while the lower ranks (who refused to accept payment in paper) were not being paid at all.” Id., p. 84. Wellington’s enlisted men knew a scam when they saw one.

11. F. William Engdahl, American Exceptionalism — Serious Distortions of the New Economic Era.

13. William Adams Brown, Jr., England and the New Gold Standard 1919-1926 (Arno Press, 1978), p. 38.

14. The text of the last notice of fixing was contained in a letter dated August 31, 1939, from N. M. Rothschild & Sons to the Chief Cashier of the Bank of England:

We have pleasure in informing you that at the time of fixing the price of Gold this morning, the market estimated that the price of 159/- represented a discount of 3d. per fine ounce, calculated at a dollar rate of 4.36½.

“Less than twenty-four hours later, Germany attacked Poland, and two days after that, Britain and France declared war on Germany. With the start of the Second World War, gold was no longer traded on open markets in the United Kingdom.”

Source: World Gold Council, Monetary History, Volume III, After the Gold Standard, 1931-1999, ex Bank of England Archives, C43/142, 1945/4, no. 129.

15. Peter L. Bernstein, The Power of Gold (John Wiley & Sons, 2000), p. 339.

16. Antony C. Sutton, The War on Gold (’76 Press, 1977), p. 110.

17. Bernstein, op. cit., p. 340.

18. Source: World Gold Council, Monetary History, Volume III, After the Gold Standard, 1931-1999, ex The Times of London, 15 March 1968, p. 1.

19. Id., ex Bank of England Archives, C43/236, 1966/2.

20. Actually, it was now a two tier price: the “free” price established in the market, and the official price of $35 per ounce, that applied to transactions among central banks.

21. The baleful effect of the dead hand of Keynesianism on contemporary English economic thought was noted over thirty years ago by Lord Rees-Mogg, former editor of The Times of London, in The Reigning Error (Hamish Hamilton, 1974), p. 96:

It is in Britain that the idea of gold is unfamiliar. Britain was naturally at the centre of the Keynesian economic revolution, but has not been equally the centre of the recent development of economic theory. A generation of economists has been brought up to believe that there was no case in the 1920s for the Bank of England, and that Keynes was not only brilliant, but obviously right. It must also be admitted that Keynes least attractive attitude, his intellectual arrogance, has influenced the personalities of some of his successors. Since the war British economic policy and policy discussion have failed to produce a coherent response to the growing inflationary threat.

22. As it happened, the FT was a tad early in announcing the demise of gold. It was not the first time. On December 13, 1997, well over a year before the present bull market in gold is generally agreed to have begun, the FT ran a lengthy piece entitled “The Death of Gold.” For the record, the afternoon Fix on April 16, 2004, the date of “Going, Going, Gold”, was $400.25.

23. The Prospectus contains a good summary of the current fixing procedure:

The morning session of the fix starts at 10:30 AM London time, and the afternoon session starts as 3 PM London time. The other members of the gold fixing [in addition to Scotiabank] are currently Deutsche Bank AG, HSBC Bank USA, Societe Generale, Barclays Bank plc. Barclays Bank plc bought the N M Rothschild Limited’s seat on the London fix for an undisclosed sum. Any other market participant wishing to participate in trading on the fix is required to do so through one of the five gold fixing members.