MPEG COMMENTARY - Page 23

March 21, 2003. Spring Special: llustrated Primer on Gold

Last week found the proprietor in Toronto attending the annual convention of the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada, enjoying the company of many ardent gold bugs, and in some instances taking advantage of their kind and much appreciated hospitality as well. At the same time, partner Bob Landis was in Houston on a tougher assignment: trying to explain to the less convinced why they would be well-advised to include some exposure to gold in their investment portfolios. His enjoyably illustrated talk, The Once and Future Money, is an excellent and timely primer on the reasons everyone should own some gold.

January 29, 2003. Gold: Cover or Cover-up?

No sooner had gold hit the first in its recent series of new six-year highs than Canada's Financial Post quoted a Toronto gold analyst: "Gold...has a huge image problem. ... It's time to stop talking about central banks and hedging strategies, and start focusing on supply, demand and the flow of capital." S. Maich, Hot, but still not respectable - Gold's image problem, December 20, 2002. Huh? The central banks are the swing suppliers, often through leasing rather than outright sales. Does anyone suggest talking about oil prices without mentioning OPEC?

A recent article in Mineweb (T. Wood, Challenges mount for Gata as gold price rises, December 16, 2002) struck the same theme, describing a segment of the Toronto gold community as distressed by GATA's sometimes aggressive tactics. Ironically, the article shed its largest tears for John Embry, the Toronto gold guru most closely identified with support for GATA's views, much to the alleged chagrin of his employer, Royal Bank of Canada. But as manager of the Royal Precious Metals Fund, Mr. Embry -- like many GATA supporters -- posted some pretty impressive investment results in 2002.

According to the bank's own figures updated as of December 31, 2002, the Royal Precious Metals Fund appreciated by 153.1% in 2002, and what's more, with three, five and ten year annual compounded total returns of 45.4%, 18.4% and 17.1%, respectively, has by far the best long-term record of any fund in the bank's stable. For purposes of comparison, the one, three, five and ten year returns for the Royal Energy Fund were 9.1%, 18%, 6.7% and 11.3%, respectively, making it the bank's second best performing fund in all but the five-year period where two other funds had marginally better returns of 7% and 6.9%. Mr. Embry's performance record is even more impressive when compared against gold funds based in the United States.

Based on figures as of December 27, 2002, from Morningstar, the February 2003 issue of Money (www.money.com) reports that the top seven performing American-domiciled stock funds in 2002 -- with returns ranging from 94.0% for Van Eck International Investors Gold A to 67.2% for Fidelity Select Gold -- were gold funds. For performance over the past three years, John Hathaway's Tocqueville Gold Fund with an annualized return of 26.8% ranked third among all stock funds. For five-year performance, Money lists only five stock funds with annualized returns in excess of 18%. The best performing gold fund was USAA Precious Metals and Minerals at 15.2%. Thus Mr. Embry is not just by far the swiftest horse in Royal Bank's stable. Among all publicly reporting North American gold funds (absent a Canadian challenger of which I am unaware), he holds the triple crown for best one, three and five-year performance.

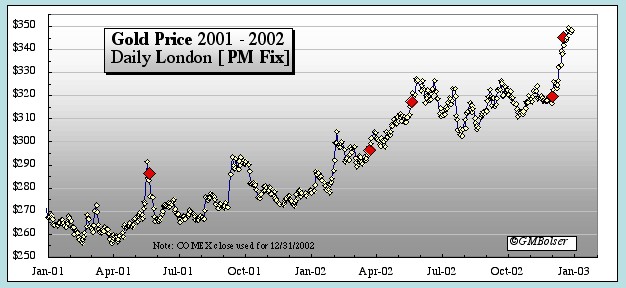

Of course, last year's outstanding performance by gold funds largely reflects the turnaround in gold prices. From $370/oz. at the end of 1996, gold finished 1997, 1998 and 1999 at around $290 and 2000 and 2001 at near $275. In 2002, gold rose more than 25% to close the year at $347 on the COMEX. The following chart by Mike Bolser traces gold's progress over the past two calendar years.

Going from left to right, the red diamonds in Mike's chart mark the following five dates and events: (1) May 24, 2001, GATA Conference in Durban, South Africa, to present its evidence of price fixing in the gold market; (2) March 26, 2002, Judge Lindsay releases Memorandum and Order dismissing the gold price fixing case on technical legal grounds but accurately republishing in some detail the factual allegations of the complaint; (3) May 23, 2002, GATA presentations by me and Bill Murphy to AMA London gold conference; (4) December 4, 2002, Gold Derivatives: Moving towards Checkmate is posted and receives more than 20,000 hits over the following two weeks; and (5) December 19, 2002, speech by Alan Greenspan to New York Economic Club (see below).

Comments suggesting that gold's year-end 2002 rally resulted in any direct way from the commentary posted here on December 4 are flattering but almost certainly incorrect. However, it is equally wrong to suggest that GATA's activities in general have somehow harmed gold's image or retarded the recovery in gold prices. Quite to the contrary, as the above chart suggests, GATA has been a significant force in accelerating the demise of a gold price fixing scheme whose general outlines are acknowledged by all but the woefully uninformed or willfully blind.

Is it time to take cyclical profits on a normal market rebound (as suggested on January 3, 2003, by Frank Capiello on Louis Rukeyser's Wall Street), or did 2002 mark just the beginning of a major new bull market for gold? The answer to this question depends in large measure on whether gold is emerging from a bear market primarily produced by natural market forces or deliberately engineered by the central banks operating in a fashion reminiscent of the London gold pool of the 1960's.

More on Gold Derivatives. Criticism of my December 4 commentary in The Gartman Letter produced at least one beneficial result: online publication of an updated analysis by Frank Veneroso et al., Gold Derivatives, Gold Lending, Official Management of the Gold Price and the Current State of the Gold Market, May 17, 2002 (www.gata.org/Veneroso1202.html; also www.financialsense.com/editorials/veneroso.htm). While this new piece makes no fundamental change in his methodology or estimate of total gold lending by the central banks (i.e., the total short physical position), it does contain three new points worthy of mention.

First, as the title suggests, Mr. Veneroso publicly opines for the first time that the central banks have been deliberately manipulating gold prices. Heretofore, he has confined his analysis to objective estimates of the size of the total short physical position.

Second, he suggests that while aggregate short positions -- particularly those of gold producers -- in the futures and forward markets may have been substantially reduced, aggregate gold loans by central banks have not. Indeed, they have continued to grow, and cannot be reduced as long as physical demand for fabrication and bar hoarding exceeds new mine supply, scrap recovery and official sales. Accordingly, any reduction in aggregate short positions in the futures and forward markets has resulted from intervention by the official sector, which, as he puts it, "has quietly taken the gold shorts from private speculators and producers and transferred them to their books. In other words, the official sector has intervened to prevent an explosive gold derivative crisis."

Third, he reports from contacts in the hedge fund industry, "a growing belief that the gold market is being managed by the official sector and that this management will at some point fail." This perception in itself constitutes a "challenge" to the central banks, and citing recent comments from the Bundesbank about its willingness to consider selling more gold, Mr. Veneroso foresees the possibility of "further official statements or actions that might be construed as part of an attempt to manage the gold price." He adds: "One or more of these statements or actions may be so extreme as to shock the market."

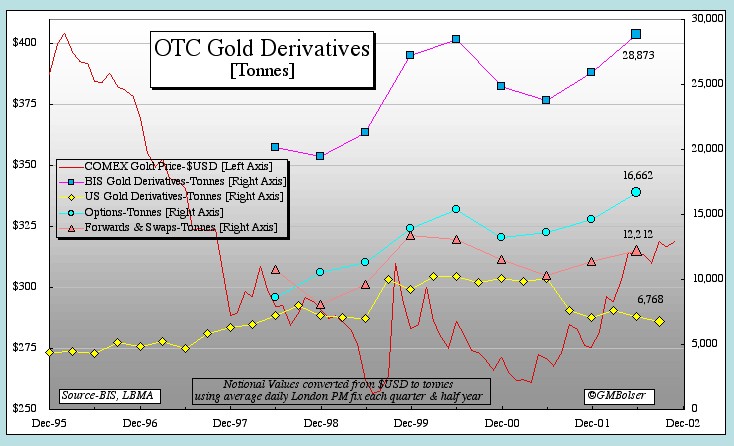

As promised in my December 4 commentary, the chart summarizing the semi-annual statistics on gold derivatives from the Bank for International Settlements has been updated by Mike Bolser to include the separate figures for forwards and swaps and for options as of June 30, 2002, as reported in table 22A of the BIS Quarterly Review released December 9, 2002. As noted previously, total gold derivatives rose 21% in the first half of 2002, from a notional $231 billion at the end of December 2001 to $279 billion at the end of June 2002. Of this $48 billion increase, forwards and swaps accounted for $17 billion and options for $31 billion. While the increase in options was almost twice that in forwards and swaps, the latter increase is particularly noteworthy in light of the reported reductions in producer hedgebooks.

Nor can these increases be readily explained as just more gilding of producer hedgebooks. For example, with respect to reducing the Normandy hedgebook which it acquired in early 2002, Newmont appears to have taken a rather different approach than it used in 2001 to reduce its own. According to its third quarter 2002 Form 10-Q, the Normandy hedgebook is being reduced as aggressively as possible through a combination of scheduled and accelerated deliveries together with "opportunistic" buy-backs whenever possible. These practices, especially if other producers are taking the same route, should reduce total forwards and swaps. Indeed, if gold producers account for most of this category, scheduled deliveries alone in the absence of new forward sales should bring down the total, and to the extent there is any systemic double counting or other overlap, total forwards and swaps should decline even faster.

According to a recent piece from Mitsui gold analyst Andy Smith, figures from several recent surveys indicate that total producer hedgebooks of over 3000 tonnes at the start of 2002 declined to under 2700 tonnes by the end of the third quarter. The failure of these reductions to make even a dent in total reported derivatives suggests that producer hedging is a relatively small portion of total forwards and swaps reported by the BIS, which at a notional $118 billion as of mid-year 2002 exceeded 12,000 tonnes when converted at the average gold price for the preceding six months. In other words, the bulk of this business appears attributable to neither producers nor fabricators but rather to the gold carry trade, primarily banks funding other activities.

In these circumstances, the continued growth of forwards and swaps and the large increase in options are consistent with: (1) leasing of additional gold by the central banks to meet physical demand that exceeds available supply at current prices; and (2) transferring risk from the bullion banks to the central banks through derivatives of all types as appropriate in particular cases, bearing in mind that some of the largest bullion banks are parts of banks generally considered too large to fail. Among these is J.P. Morgan Chase (JPM), with gold derivatives amounting to a notional $41 billion (or approximately 4000 tonnes at $320/oz.) as of September 30, 2002, according to figures from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. See GOLD MARKET REGRESSION CHARTS.

While failing to shrink total gold derivatives or even total forwards and swaps, ongoing reductions in producer hedgebooks have deprived the central banks of the principal fig leaf they used to cover their suppression of gold prices through the gold carry trade. Still, it appears that the central banks are continuing to hemorrhage gold. Basic principles of triage would suggest that at this point the central banks should try to manage gold prices higher so as to reduce and eventually stop unwanted outflows from their vaults while at the same time trying to prevent any explosion in gold prices that could cause a gold derivatives crisis.

Rising Gold Prices Pressure Banks. Notwithstanding its mammoth position in gold derivatives as reported to the OCC, William Harrison, JPM's CEO, says (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/gata/message/1363): "We don't have any real exposure to gold. I don't know where that rumor keeps coming from, but it's not true." Indeed, JPM has asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to investigate the source of these rumors (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/gata/message/1366), which have hurt its stock price. Of course, a substantial portion of JPM's gold derivatives may represent positions put on for or otherwise backed by the Fed, making Mr. Harrison's statement largely true. But in that case, neither the Fed nor JPM is likely to say so publicly. Thus, to keep its gold derivatives from weighing on its stock price indefinitely, JPM's request to the SEC may be nothing more than a ploy to try to get a clean bill of health on gold from another arm of the federal government. If so, the strategy could backfire.

In a public letter to the SEC (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/gata/message/1371), James Turk raises the possibility that JPM may have used gold to fund its commodity swaps with Enron. Seconded by GATA (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/gata/message/1372), he has requested the SEC to expand its investigation to include: "...whether JPM's disclosure about its gold derivatives has been sufficient, and indeed whether the statements by its management about JPM's gold exposure are not false or misleading."

On January 14, 2003, the Bank of Portugal announced that it sold 15 tonnes of gold in December 2002. See K. Gooding, Bank gold sales flare up again (Mineweb, January 19, 2003). Informed speculation in the bullion bank community leans to the view that these sales represented deliveries on call options written in 1997 or 1998 that went into the money as gold prices rose last December. If this speculation is correct, the fact that the calls were settled by delivery rather than through a financial transaction tends to confirm reports of extreme tightness in the physical market.

In any event, the sale puts a new and heretofore unexpected seller on the list of signatories to the Washington Agreement for whom room must now be made within the annual collective sales quota of 400 tonnes. More interestingly, if the sale presages further forced deliveries on written calls by the Bank of Portugal or other signatory banks, it raises questions regarding what, if any, arrangements are provided for such sales under the agreement and whether quotas already assigned to certain central banks may have to be reduced.

More significant than the sale itself is the simultaneous unveiling of a previously neglected footnote in the Bank of Portugal's 2001 annual report (www.bportugal.pt/publish/relatorio/Chap_IV_01.pdf (scroll down to 9th page)), which discloses that out of its then 606 tonnes of gold reserves, more than 70% had been leased (52 tonnes) or swapped (381 tonnes), leaving only 173 tonnes in the vault. Bearing in mind that in the wake of the sharp rally in gold prices triggered by the Washington Agreement, the International Monetary Fund loosened its reporting rules to permit swapped gold to be treated in the same manner as leased gold (see "The Macroeconomic Statistical Treatment of Securities Repurchase Agreements, Securities Lending, Gold Swaps and Gold Loans," www.imf.org/external/bopage/pdf/99-10.pdf; see also www.gata.org/bofi.html), the relatively large amount of gold swaps suggests that the Bank of Portugal may have been pressed into service at that time.

What is most important, however, is the huge relative volume of leased and swapped gold to vault gold, a ratio which not only tends to confirm the higher estimates of the short physical position but also adds to suspicions that certain other central banks, especially from the euro area, have acted similarly. In announcing the Portuguese sale, the governor of its central bank described its gold reserves as "excessive" for a country in a monetary union, a further indication that members of the euro area are continuing to manage their gold reserves primarily as national assets rather than as gold reserves held in common and available to support the euro.

Fed Rediscovers Gold. In a speech on November 21, 2002 ("Deflation: Making Sure 'It' Doesn't Happen Here"), Fed governor Ben S. Bernanke observed:

Like gold, U.S. dollars have value only to the extent that they are strictly limited in supply. But the U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. By increasing the number of U.S. dollars in circulation, or even by credibly threatening to do so, the U.S. government can also reduce the value of a dollar in terms of goods and services, which is equivalent to raising the prices in dollars of those goods and services. We conclude that, under a paper-money system, a determined government can always generate higher spending and hence positive inflation.

Speaking on "Issues for Monetary Policy" to the Economic Club of New York on December 19, 2002, Fed chairman Alan Greenspan began:

Although the gold standard could hardly be portrayed as having produced a period of price tranquility, it was the case that the price level in 1929 was not much different, on net, from what it had been in 1800. But, in the two decades following the abandonment of the gold standard in 1933, the consumer price index in the United States nearly doubled. And, in the four decades after that, prices quintupled. Monetary policy, unleashed from the constraint of domestic gold convertibility, had allowed a persistent overissuance of money. As recently as a decade ago, central bankers, having witnessed more than a half-century of chronic inflation, appeared to confirm that a fiat currency was inherently subject to excess.

Then, echoing Mr. Bernanke but in more measured tones, Sir Alan hammered home the Fed's determination to do whatever it must to avoid any widespread price deflation:

One also should not overstate the difficulties posed for monetary policy by the zero bound on interest rates and nominal wage inflexibility even in the absence of faster productivity growth. The expansion of the monetary base can proceed even if overnight rates are driven to their zero lower bound. The Federal Reserve has authority to purchase Treasury securities of any maturity and indeed already purchases such securities as part of its procedures to keep the overnight rate at its desired level. This authority could be used to lower interest rates at longer maturities. Such actions have precedent: Between 1942 and 1951, the Federal Reserve put a ceiling on longer-term Treasury yields at 2-1/2 percent. With respect to potential difficulties in labor markets, results from research remain ambiguous on the extent and persistence of downward rigidity in nominal compensation.

Clearly, it would be desirable to avoid deflation. But if deflation were to develop, options for an aggressive monetary policy response are available.Governor Bernacke also cited the Fed's 1942-1951 purchases of longer-term Treasury securities to cap their yields. However, those purchases took place under a monetary regime in which the dollar was credibly defined as a specified weight of gold. What is more, no one considered those purchases to represent any sort of immediate threat to the dollar's gold parity. Were the Fed to engage in such purchases under today's unlimited fiat money regime, they would be considered highly inflationary and would most likely result in a plunging dollar and rising longer-term rates. Interestingly, last year when the yield on the 30-year Treasury bond stubbornly refused to break significantly below 5%, the official remedy was to cease further sales of new bonds rather than resort to purchases by the Fed.

Predicted Reintroduction of Gold Cover Clause. As "Mr. Gold" in the 1970's, James Sinclair was sufficiently prescient to exit the gold market at the top fearing that the new Fed chairman, Paul Volcker, would prove quite serious about rescuing the dollar, and therefore bearish for gold. Today Mr. Sinclair believes that Sir Alan's December 19 speech marks a similar turning point, but one bullish for gold. In short, and without much support from a literal reading of the text, he thinks that the Fed chairman has signaled a possible reintroduction of the gold cover clause should it be necessary to support the dollar in the face of massive reflationary efforts by the Fed. See J.E. Sinclair, The Gold Cover Clause: The Deflation Solution (MineSet, December 23, 2002).

Nor is Mr. Sinclair alone in his belief that Sir Alan's extraordinary December panegyric to the gold standard may have carried a message regarding the future use of gold prices to guide monetary policy. See R. Brenner, Is Greenspan hinting at a new gold standard?, National Post (January 21, 2003). However, Mr. Sinclair's idea involves a good deal more than merely using gold prices as some sort of informal guide. Rather, he is suggesting a possible new formal and explicit statutory link between the dollar and gold.

During the gold standard era, central banks commonly operated under statutes that mandated specified amounts of gold as backing or "cover" for their paper currency in circulation and sometimes certain other liabilities as well. As central banking replaced private banking, gold cover clauses simply carried over into the official sector prudential rules developed in the private sector to support the promise of gold redeemability for paper bank notes.

Until 1945, the Fed was required to hold gold reserves (or gold certificates issued by the Treasury on its gold reserves) equal to 40% of its notes outstanding and 35% of its deposit liabilities. These requirements were lowered in 1945 to 25% for both notes and deposits. In 1965, the gold reserve requirement for deposits was repealed, leaving only the 25% requirement against currency in circulation, and this requirement was dropped in 1968. Thus, from World War II to shortly before the closing of the gold window in 1971, whenever the gold cover clause threatened to bite, it was progressively relaxed and finally eliminated altogether.

Prior to its new constitution effective January 1, 2000, Switzerland was required to maintain a 40% gold cover for its currency. However, as a consequence of joining the IMF in 1992, Switzerland became obliged to abrogate this provision since it violated the Fund's prohibition on member countries linking their currencies to gold. In fact, until 1998 Switzerland valued its gold at historic prices that, when converted to market, yielded gold coverage greater than 100% for every Swiss franc in circulation. See F. Lips, Freedom is Lost in Small Steps (FAME, December 28, 2002); see also, F. Lips, The Gold Wars: The Battle Against Sound Money As Seen From A Swiss Perspective (FAME, 2002), pp. 180-201, for a more detailed history of Switzerland's gold cover clause and its demise.

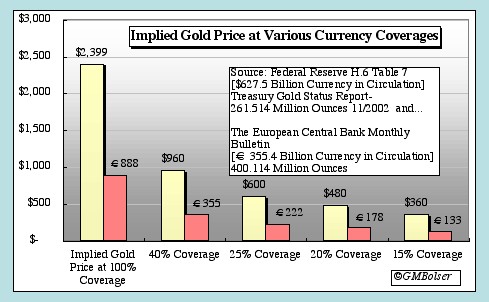

The following chart by Mike Bolser shows the dollar and euro gold prices required to meet various gold cover requirements based upon current amounts of currency outstanding and assuming that all claimed official reserves, including leased and swapped gold, are available as cover. Mike has also assumed that all national gold gold reserves, not just those actually transferred to the European Central Bank, would be available as cover for the euro.

By putting some sort of credible limit on the Fed's ability to create money, the reinstitution of a gold cover clause might offer the Fed a means to reflate aggressively without causing panic dumping of dollars in the process. Mr. Sinclair has suggested "a modernized and revitalized Gold Cover Clause ... tied to the ability to expand M3 directly." J.E. Sinclair, That Sinking Feeling: Deflation in Goods and the Dollar (MineSet, January 19, 2003). More recently, he has provided some further details on how this concept might work (J.E. Sinclair, Gold To Be Remonetized! (Mine Set, January 23, 2003):

Gold is headed back into the system by a modernized and revitalized Federal Reserve Gold Certificate Ratio then tied to the expansion of M3 (the broad monetary aggregate figure). The value of Treasury gold on the day of enactment will be considered to be that value which is required to have that size M3. From that point forward, more gold or a higher price for gold will be required in order to expand the broad based monetary aggregate beyond a modest percentage. The Treasury could simply benefit from a higher price or could buy gold in the open market to effect a higher price should the need arise to expand beyond the present level in M3 beyond a predetermined expansion of 3% per year.

As envisioned by Mr. Sinclair, a new gold cover clause would act as a brake on the creation of money, but neither domestic gold redeemability for Federal Reserve notes nor international gold convertibility for foreign official dollar balances would be restored. What is more, the gold cover requirement itself would not apply to currency, deposits or even the monetary base, all of which are subject to reasonably direct control by the Fed, but to a much broader monetary aggregate (M-3) for which there is no historical experience with gold cover ratios.

However, whether any new gold cover clause is linked to one or another of the monetary aggregates or just to currency in circulation, several basic and interrelated questions immediately arise, including: (1) what percentage of cover to use; (2) what gold price to use in determining the percentage of cover; (3) what happens if gold prices decline below that level; (4) what gold reserves qualify as acceptable cover; and (5) whether other countries will adopt the same or a similar system.

Assuming a gold cover clause based on market prices or a recent average thereof, what happens if gold prices fall significantly after the maximum amount of currency permitted at higher gold prices is issued? Does the central bank buy gold, augmenting its reserves and quite possibly driving up the price as well, or does it purchase its currency, shrinking the supply? Of course, it could do some of each, perhaps buying gold with the currency it purchases. However, a gold cover clause that operates with a high degree of sensitivity to current gold prices might appear too much like the gold standard, bringing along all its baggage about automatic (and unwanted) deflationary adjustments in the money supply. One method of cushioning this problem might be to set the cover price periodically at an average of gold prices over some recent time period, or at a percentage thereof.

As the Swiss experience shows, gold cover clauses are currently considered to violate IMF rules. However, assuming this problem could be resolved, a larger issue is whether other nations would opt for gold cover clauses if the United States did so. In that event, the demand for gold by central banks would almost certainly be larger and grow faster, quite possibly affecting selection of the most appropriate percentage level for the required cover. Another problem is that due to their different relative levels of gold reserves, nations vary with respect to what percentage of gold cover is feasible or practical. As Mike's chart shows, at current gold prices the euro area could meet a gold cover requirement of 40% on its currency outstanding whereas the United States would have to struggle to meet a 15% requirement.

Of course, Mike's chart assumes that the governments included have the gold reserves that they claim to have. This assumption is highly questionable, as Portugal has just demonstrated and as much of the evidence collected by GATA over the past few years shows. Whatever its precise mechanics, a gold cover clause cannot be wholly credible and effective in the absence of three basic attributes: (1) a clear definition of the type and quality of gold reserves that qualify as cover; (2) verification of the quantity of these reserves, presumably including an independent audit by a reputable accounting firm; and (3) legal enforceability, including meaningful sanctions against officials responsible for any violations.

Cover versus Cover-up. There has not been an outside audit of the U.S. gold stock within living memory. Recent speculation that a significant portion of it has been swapped out is based on various pieces of evidence, including: Fed general counsel Mattingly's reference to gold swaps by the Exchange Stabilization Fund, since denied, in the minutes of a 1995 meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee; the U.S. Mint's reclassification or redesignation of a large portion of U.S. gold reserves as "deep storage" gold; and accounting instructions issued by the ECB giving a gold swap between one of its member banks and the Fed as an illustrative hypothetical. For citations and links, see Plaintiff's Affidavit, paragraphs 29 and 31-33, and Plaintiff's Second Affidavit, paragraphs 8 and 32-37,

In the course of thus far unsuccessful efforts to obtain details from the Bundesbank on its gold reserves and any gold swaps it has with the United States, one of GATA's German supporters came across some interesting but mostly forgotten details on U.S. gold reserves. Professor Antony C. Sutton in The War on Gold ('76 Press, 1978), pp. 114-116, described an unaudited report by the U.S. Mint detailing the composition of U.S. gold reserves as of November 30, 1973. It showed that of then total 255 million ounces, 206 million consisted of 400 oz. bars of a fineness between .890 and .916 with almost another million ounces having a fineness between .917 and .994. Thus, at that time, more than 80% of the total U.S. gold stock did not meet the standard good delivery requirement of .995 or better.

Professor Sutton's account is confirmed by the late James Blanchard in Confessions of a Gold Bug (Adam Smith, 1990), pp. 76-77:

One of the other projects NCMR [National Committee for Monetary Reform] got involved with was to ask for an auditing of the Fort Knox gold. There was great resistance at first, but finally the Treasury listed the actual number of gold bars, their size and purity. Until then the Treasury had been claiming that we had 264 million ounces of gold in reserve, and that it was made up mostly of .995 to .999 pure bars. What we found was that it was almost entirely made up of melted gold coins from the 1930s at .917 (22-karat) purity.

The old coinage standard was 22-karat or .916667 (22 divided by 24). Prior to the inventory described by Messrs. Sutton and Blanchard, gold of coinage standard fineness was not thought to constitute a large percentage of U.S. gold reserves. A somewhat confusing footnote in M. Friedman et al., A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960 (Princeton Univ. Press, 1963), pp. 463-464 n. 45, had put the amount of gold coinage actually turned in at about half of what should have been, which itself was calculated at less than 28 million ounces. Notwithstanding gold auctions in 1977-78 and the return of some IMF gold, the general composition of the U.S. gold stock, currently reported at approximately 262 million ounces, is unlikely to have changed significantly since 1973.

Although there is no obvious reason that 22-karat gold bars should not be used for purposes of meeting a gold cover requirement, the same cannot be said for leased or swapped gold. The fact that so much of the U.S. gold stock apparently fails to meet the good delivery standard increases the chances that any surreptitious disposals have been effected through gold swaps for good delivery bars. Otherwise, the need for further refining of coin melt bars could well have triggered unwanted market rumors.

In the case of the United States, the legal weight of any new gold cover clause would be subject to serious doubt absent a constitutional amendment. Unlike Switzerland, which adhered to the gold cover requirements of its former constitution until those provisions were properly amended, the United States has implemented its unlimited fiat money system by statute and in complete disregard of the monetary provisions of the Constitution. See Money in Court: Paving the Road to Ruin. and Petition for Certiorari in Walter W. Fischer v. City of Dover, N.H., U.S. Supreme Court, No. 91-221.

Given this statutory history, any new U.S. gold cover clause is likely to be regarded as little more than a political gimmick unless adopted by a constitutional amendment. On the other hand, a gold cover clause implemented in this manner would provide an opportunity at long last to bring the actual monetary system and the Constitution into harmony with each other. Desperate times often call for desperate measures; sometimes they are taken; occasionally they succeed. The Constitution itself should remind us that even in government miracles happen, and that is almost certainly what a successful reintroduction of the gold cover clause by today's political establishment in Washington, D.C., would require.

December 4, 2002. Gold Derivatives: Moving towards Checkmate

"L'État, c'est moi," famously proclaimed Louis XIV. Recently knighted by the Queen, Sir Alan is the U.S. dollar. When the ancien régime finally fell, the Sun King had been in his grave for almost a century. New statistics on gold derivatives together with other recent anomalies in the gold market suggest that Sir Alan may not be so fortunate, and that gold is close to pushing today's dollar-based international monetary regime into checkmate.

Gold Derivatives in a Nutshell. For reporting purposes, over-the-counter derivatives are generally grouped into two categories: forwards and swaps on the one hand and options on the other. Before trying to make sense of the most recently reported data on gold derivatives, a short (and simplified) review of their relationship to the short physical gold position of the bullion banks may be helpful.

Central banks, or at least some of them, lend or lease gold from their vaults to bullion banks at relatively low interest rates -- say 1% to 2% -- known as lease rates, ostensibly to earn a small return on an otherwise "sterile" asset. The bullion banks, which have no direct use for the metal, function as intermediaries, seeking to earn a small profit on the spread between the lease rates and higher returns available elsewhere while curtailing their own risk. Accordingly, they sell the leased gold into the spot market and invest the proceeds from the sales at a higher rate -- say 5% to 7%. As a consequence, they are short the physical gold that they must later return or repay to the central banks, and therefore exposed to the risk of higher gold prices when they have to cover.

To hedge this risk, the bullion banks go long in the forward market, where they exchange part (usually most) of the higher returns on the proceeds from the sales of the leased gold for agreements to deliver physical gold to them in the future. In the case of gold producers, these transactions include forward sales of future production and gold loans to fund new production. The premium or "contango" that the producer receives over the spot price for a forward sale represents the difference between the interest rate available on the proceeds from sale of the leased gold (e.g., LIBOR or the U.S. T-bill rate) and the lease rate, less of course a fee for the bank.

In the case of transactions with non-producers or the gold carry trade, the banks' counterparties have no obvious source of future gold for repayment other than what they can purchase in the market. Like the bullion banks, they are exposed to the risk of higher gold prices when the time arrives for repayment of the physical gold. Accordingly, non-producers typically try to hedge their risk with options, also purchased from the bullion banks and in turn delta hedged by them. (Delta hedging is described in a prior commentary, The New Dimension: Running for Cover).

Looking at just gold derivatives, including both forwards and options, there are two sides to every contract, a buyer for every seller and a seller for every buyer. Of course, taking all the gold derivatives of any particular bullion bank, it might be net long, net short or market neutral. But looking at the gold lending by the central banks to the bullion banks, there is a short physical gold position. It consists of all the gold that has been leased (or swapped) from the vaults of the central banks, sold into the market by the bullion banks, and is now owed by their customers to them under derivatives contracts, and by them directly in physical form to the central banks.

Short Physical Gold Position of the Bullion Banks. What is the size of the total short physical gold position, or put another way, how much gold from their vaults have the central banks as a group leased, swapped or deposited into the market through the bullion banks? In round numbers, the answer from conventional industry sources such as Gold Fields Minerals Services and the World Gold Council is 5000 metric tonnes, including 3000 tonnes for producer hedging, which leaves some 2000 tonnes for other purposes, e.g., the gold carry trade and inventory borrowing by gold fabricators.

Although 3000 tonnes of producer hedging appears reasonable based on the published financial reports of gold producers, the total of 5000 tonnes cannot be confirmed from the published financial reports of the central banks, the International Monetary Fund, the Bank for International Settlements or the bullion banks. Indeed, the IMF expressly authorizes central banks to report their gold holdings as a single entry without separately identifying gold in the vault from gold receivables, including both leased gold and gold swaps. See, e.g., "The Macroeconomic Statistical Treatment of Securities Repurchase Agreements, Securities Lending, Gold Swaps and Gold Loans," www.imf.org/external/bopage/pdf/99-10.pdf; see also www.gata.org/bofi.html. Accordingly, while the IMF reports that official gold reserves total some 33,000 tonnes, it purposefully hides the amount held in physical bullion as opposed to paper claims on gold.

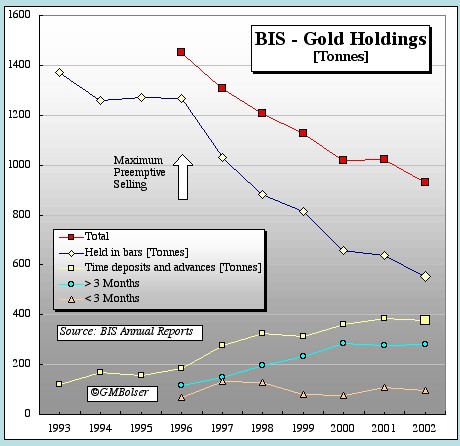

Among the major central banks, only the Swiss National Bank and the BIS, which operates the central bank for central banks, provide any figures on the amount of their gold lending. The BIS offers its member central banks (and certain other international financial institutions such as the IMF) a traditional gold banking facility, which is depicted graphically in the chart below by Mike Bolser.

In sum, the picture at the BIS since 1995 is more lending with less gold. Two points to note: (1) as of March 31, 2002, the BIS had loaned out approximately half the total gold on deposit with it by central banks; and (2) the BIS holds physical gold reserves that exceed its gold liabilities (deposits) by nearly 200 tonnes (about the amount of gold held for its own account). Gold lending on this scale by the central banks themselves would imply a short physical position in excess of 15,000 tonnes, but one against which the bullion banks hold virtually no physical reserves.

A total short physical position of 5000 tonnes also appears insufficient to fill the gap that has existed for several years between physical demand or offtake and new mine supply, official sales and scrap recovery. In an analysis presented to the GATA conference in Durban, South Africa, in May 2001 (alternate URL: http://www.gata.org/veneroso_pdf.html), Frank Veneroso estimated that this net physical deficit amounted to at least 10,000, and possibly as much as 16,000 tonnes, implying a short physical position of equal size. (Note: Since the date of this commentary, a more recent update of his analysis has become publicly available (www.gata.org/Veneroso1202.html; also www.financialsense.com/editorials/veneroso.htm), Frank Veneroso et al., Gold Derivatives, Gold Lending, Official Management of the Gold Price and the Current State of the Gold Market, May 17, 2002, presentation to Fifth International Gold Symposium, Lima, Peru.)

Much of Mr. Veneroso's demand analysis consisted of filling in lacunae in otherwise apparently reliable statistics from the WGC. In the second quarter of this year, the WGC changed its system for reporting physical demand (www.gold.org/value/markets/Gdt/index.php), and in connection therewith transferred much of the responsibility for data collection to GFMS. That firm's close ties to the bullion banks have undermined confidence in its estimates of total gold lending by central banks, and the same concerns now infect the WGC's new demand figures.

Estimates of the total short physical position by GFMS and Mr. Veneroso disagree by as much as 10,000 tonnes, or four years of new mine production. Both estimates rely in large measure on non-public information gathered from industry contacts. Neither, for the reasons already stated, can be confirmed or rebutted on the basis of published balance sheet or official reserve figures from the central banks or the IMF. However, published data on gold derivatives is available from several sources, including the BIS. On analysis, it undercuts the estimate by GFMS and tends to confirm Mr. Veneroso's.

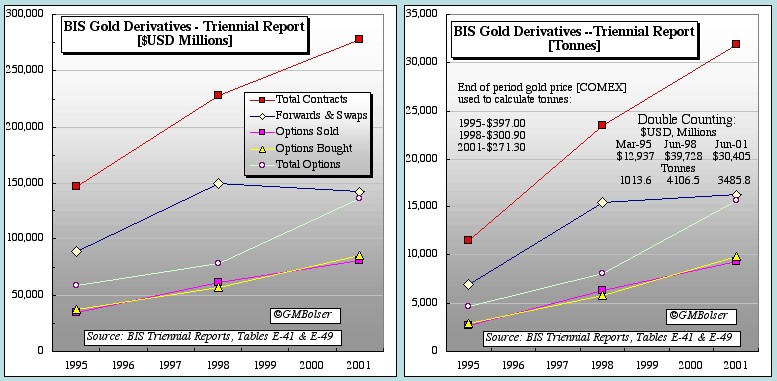

Statistics on Gold Derivatives. In addition to its regular semi-annual statistics on the OTC derivatives of major banks and dealers in the G-10 countries, the BIS publishes triennial surveys of derivatives on the books of banks and dealers in almost 50 countries. Mike Bolser's side-by-side charts below summarize the gold derivatives data contained in the three triennial surveys to date, the most recent being as of June 30, 2001 (www.bis.org/press/p020318.htm). (Note: Options sold and options bought are reported in gross numbers but total options are adjusted for double-counting, i.e., where reporting banks or dealers are both seller (writer) and buyer on the same option.)

The BIS reports end-of-period position data, not turnover data for a period as some used to argue. Even so, interpreting the BIS data leaves considerable room for questions, debate and disagreement, especially when the data is used to work backwards to an estimate of total gold lending by central banks. Just converting dollar notional value figures into tonnes requires an assumed gold price. While the BIS tries to eliminate the double-counting of contracts where reporting banks or dealers are on both sides of the same instrument, the process is unlikely to be error free, and other forms of double-counting may exist. What is the reporting, for example, if gold swapped by a central bank with one bullion bank is loaned by that bank to another, which then sells the gold in connection with a forward contract?

Any interpretation of the BIS data must recognize the different financial mechanics of forwards and swaps as compared to with those of options. Forwards imply a sale of borrowed gold by a bullion bank in order to raise funds that can be invested to earn a spread. Similarly, swaps are spot sales of gold combined with simultaneous forward purchases of equal weight. The proceeds from sale of the leased or swapped gold are essential to earning a return on the transaction. Options, at least from the perspective of a sophisticated writer like a bullion bank, are normally an attempt to capture the premium paid by the buyer while eliminating adverse price risk through delta hedging. Option writers do not require leased or swapped gold to earn a return. What is more, in many cases purchasers of call options are hedging future repayment obligations arising from forwards or swaps.

The options data reported by the BIS almost certainly reflects much of the same borrowed gold that is covered by its data on forwards and swaps. However, not all the options data can be dismissed as mere double-counting of the short physical position implied by the figures on forwards and swaps. In addition to leasing gold, some central banks also write call options as a method of earning a return on their gold. Before hedging became a dirty word, gold mining companies frequently wrote call options, and in many cases applied premiums earned on the calls to purchases of put options for downside price protection. Call writing by central banks or producers, while not immediately adding to the short physical position, creates further contingent liabilities against both the gold supplies that have funded it and those being looked to for repayment.

Taking the gold derivatives data reported by the BIS as as whole, the totals for forwards and swaps when converted to tonnes at some reasonable price appear to offer a pretty good proxy -- admittedly imprecise -- for the total short physical position. Viewed in this light, these figures align quite closely with Mr. Veneroso's estimate of a total short physical position in the range of 10,000 to 15,000 tonnes. So far as I am aware, except for the discredited argument in a WGC study addressed in a prior commentary that the BIS figures represent turnover rather than position data, no one has undertaken in print to reconcile or explain the 5000 tonnes of total gold lending estimated by GFMS with the gold derivatives figures reported by the BIS.

Some have pointed out that forwards and swaps include gold borrowed into inventory by jewelry manufacturers and other gold fabricators which has not yet been sold into the market. In The Gold Book Annual 1998, Mr. Veneroso estimated that total fabricator borrowings might reach 2000 tonnes. Whatever the amount, borrowed gold in fabricator inventories is destined to be sold. What is more, it is an amount that should tend more to roll over than to rise, and could well fall with a shrinking spread between interest rates and lease rates as has occurred over the past year.

If producers only account for around 3000 tonnes and fabricators for not more than 2000 tonnes of a short physical position exceeding 10,000 tonnes, who accounts for the remainder? To quote The Gold Book (at 51): "Given the many instances of gold borrowings for non-gold purposes that have come to our attention, it does not seem implausible that many bullion dealers with access to official gold borrowings have used these low cost gold loans for general corporate purposes or have lent this gold to borrowers for non-gold uses." In other words, the biggest borrowers of gold are likely the bullion banks themselves, not for their gold banking operations but for purposes of general corporate funding.

Recent Data on Gold Derivatives. The semi-annual statistics on gold derivatives from the BIS are significant not only for the absolute values reported but also for the trends disclosed. The most recent report in this series, released on November 8, 2002, covers the period ending June 30, 2002 (www.bis.org/publ/otc_hy0211.htm). Total gold derivatives rose 21% in the first half of 2002, from a notional $231 billion at the end of December 2001 to $279 billion at the end of June 2002. These figures together with those from earlier reports are shown in the chart below by Mike Bolser. (Note: Since the date of this commentary, the chart has been updated to include the separate figures for forwards and swaps and for options as of June 30, 2002, as reported in table 22A of the BIS Quarterly Review released December 9, 2002.)

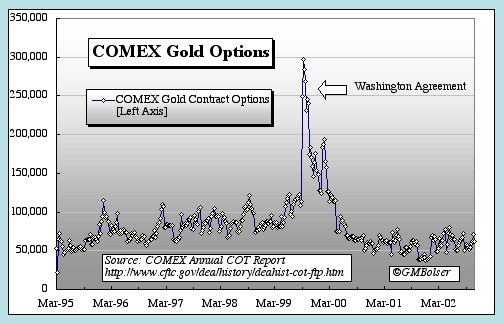

Like the increases in gold derivatives at J.P. Morgan Chase and Citibank during this year's first quarter (see commentary at GOLD MARKET REGRESSION CHARTS), the first half increases reported by the BIS are rather surprising given the many reports of gold mining companies aggressively trimming their hedgebooks combined with historically low interest rates reducing the lure of both producer forward selling and the gold carry trade. However, these increases do repeat the pattern that followed the Washington Agreement in the fall of 1999, i.e., heavy use of derivatives, especially options, to try to contain rising gold prices. As explained in The New Dimension: Running for Cover, purchased call options provide traders with ammunition for shorting gold.

However, although the notional value of OTC gold options has moved back toward the peak levels reached in the fall of 1999, open interest on COMEX gold options, as shown in the chart below, has traced an opposite route, declining to 1995 levels that are far from the highs of 1999.

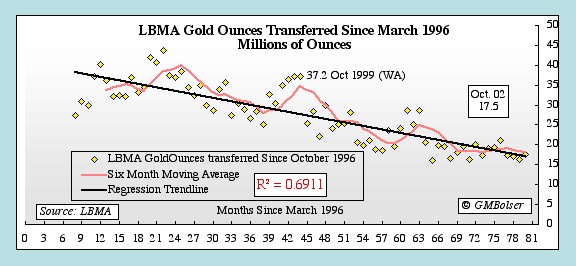

Similarly, turnover on the London gold market has been in steady decline, as shown in the chart below that Mike Bolser updates monthly in GOLD MARKET REGRESSION CHARTS. Since the LBMA is presumably where a lot of the delta hedging on gold options is effected, this decline seems inconsistent with the growth of OTC gold options assuming they are properly hedged.

Gilding Producer Hedgebooks. In part at least, the recent increases in OTC gold derivatives appear to reflect a new phenomenon in producer hedgebooks. Call it gilding: the practice of not closing hedges but rather of trying to offset them with other hedges. For example, forward sales are not unwound or delivered into but rather offset with forward purchases, or call options sold are offset with call options purchased or other negotiated arrangements.

As Bob Landis noted in the recent update of his commentary on Barrick's hedgebook, the king of hedgers is now reporting spot deferred forward contracts on 16.9 million ounces “net of 300,000 ounces of gold contracts purchased.” Footnote 23 to Harmony's annual report for the year ending June 30, 2001, discloses forward purchase contracts on almost 800,000 ounces and calls purchased on another 100,000 ounces as against gross forward sales of just over 1 million ounces and calls sold on almost 1.5 million ounces. Similarly, footnote 9 to Newmont's annual report for 2001 discloses that in September 2001 it entered into transactions closing out certain written call options with a series of forward sales contracts calling for physical deliveries at future dates and prices ranging from $350/oz. in 2005 to $392/oz. in 2011. The same footnote also describes a forward sale contract on 483,000 ounces entered into in July 1999, adding: "Newmont entered into forward purchase contracts at prices increasing from $263 per ounce in 2000 to $354 per ounce in 2007 to coincide with these semi-annual delivery commitments."

Whatever its other failings, Jessica Cross's study, Gold Derivatives: The market view, sponsored and published in August 2000 by the WGC, contains a useful stand-alone section (chapter 5) describing the principal derivative products then in use by the gold mining industry. She identifies not less than seven types of forward contract, in each case stating: (1) that its impact on the gold price is immediate because "the executing bank borrows the equivalent amount of gold and sells it immediately into the market"; and (2) that among the "advantages to the user" is that it "can be unwound before delivery." Nowhere does she identify forward purchase contracts either as the means for unwinding forward sales or as a product in use by the producers.

Unlike standardized exchange-traded gold futures and options, OTC gold derivatives are bilateral contracts -- frequently containing quite complex provisions -- tailored to the specific requirements of the parties. Thus, unlike exchange-traded futures and options which can be unwound by closing or offsetting market transactions, OTC derivatives can be unwound only pursuant to applicable contractual provisions, if any, or by mutual agreement between the parties. Failing that, a producer can try to purchase an offsetting contract of some variety from a different bullion bank, but in that event incurs additional credit risk.

In a liquid market with prices set by unfettered market forces, reaching agreements to unwind or offset forward contracts or written calls ought to be relatively simple. However, in a tight physical gold market characterized by capped prices and a mammoth short physical position, it is unlikely that bullion banks would willingly let producers escape their forward delivery commitments except perhaps on payment of very steep premiums. Rob McEwen, the irrepressible CEO of Goldcorp, a producer that proudly eschews hedging, recently tested the liquidity of the spot market by placing an order to purchase 40,000 ounces and encountered significant constraints in availability (www.goldcorp.com/investor/pdf/11-08-02.pdf). Considerable anecdotal evidence of like import exists notwithstanding the WGC's recent report of slower physical demand.

Hence the question Bob Landis posed is a good one: Who sold Barrick (and the other producers) their forward purchases? And why? Other than gold producers, the usual sellers of forward contracts on gold are central banks, which sometimes implement official gold sales in this manner. Some past spikes in lease rates have been attributed to one central bank or another calling in or failing to roll over a lease in order to meet delivery on a forward sale. But to sell gold forward, especially where physical delivery is contemplated, is a risky business absent assured availability of the metal when delivery must be made. Accordingly, with producers as a group reducing their forward sales and assuming that the bullion banks are not taking on unprecedented levels of naked risk, it appears that the central banks themselves must -- in one way or another -- be standing behind the forward purchases of the producers.

In this event, several important questions about the Washington Agreement and its anticipated renewal are presented. Why are total gold derivatives rising if the central banks are observing their undertaking not to increase gold lending? How are forward sales handled? Are they counted as sales on the date of the contract, the date of delivery, or not at all if the contract is unwound before delivery? What happens if a lease is converted to a sale, as for example because the lessor cannot obtain gold for repayment, or cannot do so without driving up prices? Do written calls only become sales when delivery is demanded, or should they be treated as sales if and when they go in the money? As it is, compliance with the Washington Agreement is impossible to verify, and its renewal is unlikely to benefit anyone except the central banks.

In the absence of any contractual means for unwinding or offsetting their forward sales or written calls, producers have only two ways to reduce their hedgebooks. First, they can accelerate deliveries from their own production. Second, they can purchase bullion at spot and deliver it or hold it for delivery into their forward commitments. But producer purchasing that pushes gold prices higher also increases the mark-to-market losses on the remaining portions of their hedgebooks. Some have argued that the recent strength in gold prices is largely attributable to producer buying in the physical market, and that gold prices are likely to weaken once producers have completed their hedgebook reductions. This argument loses much of its force, however, if producers are mostly gilding their hedgebooks, as their own financial reports and the recent increases in gold derivatives suggest.

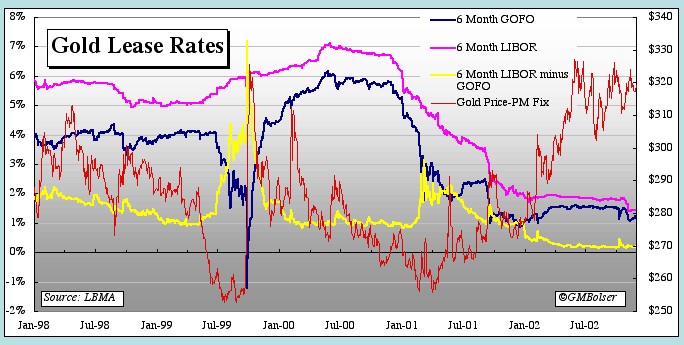

Conundrum of Current Lease Rates. Currrent low lease rates are in apparent conflict with the reports of tightness in the physical gold market. Before addressing this conundrum, another short and simple review may be helpful.

Currencies and gold have two sets of prices: the prices at which they are exchanged for each other, i.e., the exchange rate or the gold price; and the prices at which they are loaned or borrowed, i.e., the interest rate or the lease rate. These prices all interact on each other in complex and sometimes quite unpredictable ways. Despite the best efforts of governments (and the WGC) to turn gold into an ordinary commodity, it continues to be treated as a currency by the markets, where forward gold prices like forward currency rates are determined and arbitraged on the basis of relative interest rates, all as explained in much more detail in The Golden Sextant, the essay from which this website draws its name.

The basic formula governing forward gold prices in a given currency is IR (interest rate, typically LIBOR) - LR (gold lease rate) = FR (gold forward rate, often referred to as GOFO). GOFO is normally positive and thus in contango, meaning that gold prices for forward delivery exceed current prices for spot delivery. But when the forward rate turns negative, as when interest rates fall below lease rates or lease rates rise above interest rates, gold goes into backwardation, meaning that spot prices exceed forward prices.

The following chart by Mike Bolser shows 6-month lease rates since January 1998 (yellow line) calculated as the difference between 6-month dollar LIBOR and 6-month dollar GOFO as reported by the LBMA (www.lbma.org.uk). When lease rates spiked in September 1999 following announcement of the Washington Agreement, which included limitations not only on sales but also on lending, gold went into backwardation but just briefly. Otherwise, the forward rate or GOFO (blue line) has remained in positive territory, but has declined with U.S. interest rates so that for the past year the contango on 6-month forward sales has rested at five-year lows.

Significantly, from the Washington Agreement until the Federal Reserve started cutting interest rates sharply in 2001, GOFO remained at relatively high levels, apparently helping to pressure gold prices (red line) lower. As U.S. rates declined, both gold prices and lease rates rose until GOFO dropped below 3%. Since then, lease rates have followed U.S rates lower, maintaining GOFO at between 1% and 2%, and gold prices have continued to show relative strength.

Don Lindley has approached backwardation in a different manner. Beginning in 1985, he has identified some 56 days, or 20 events counting consecutive days as one event, when settlement prices on the front two COMEX gold contracts were in backwardation. He found no instances in which the backwardation extended into further out contracts, indicating that these COMEX events are more related to transitory imbalances in the physical market than to lease rates per se. Don's chart below shows the days and events of COMEX backwardation from January 1998 to the present, the same period covered by Mike's chart above. Don reports that the three events of COMEX backwardation this year, including a major one of six days at the end of July (identified by its flat top), have coincided with the expiration of European options (second business day before the end of the month). He interprets them as bullish indicators reflecting European physical demand hitting a tight market.

Veteran gold analyst Martin Murenbeeld, whose list of clients (www.murenbeeld.com/clients.htm) includes producers on both sides of the hedging debate, has published a strong defense of Barrick's hedging program in which he argues (emphasis in original): "There should be an 'economic' cost to hedging, insofar as 'risk takers' need to be compensated for accepting a risk the producer does not want to bear." Stating an opinion shared by many opponents of hedging, he adds: "I am inclined to say that because central banks have lent their gold at too low lease rates however, there has been a definite advantage to hedging gold -- the contango has been higher than it should have been in a perfectly competitive market these last 15 or so years."

Why have the central banks subsidized through low lease rates not only producer hedging but also fabricator borrowing and the gold carry trade? Dr. Murenbeeld does not address this question, but fundamentally there are only two possibilities (not necessarily mutually exclusive): (1) stupidity, or at least a cavalier and amateurish assessment of risk; or (2) an intent and purpose to drive gold prices lower by adding to current supply.

In discussing the specifics of Barrick's hedgebook, Dr. Murenbeeld makes another important point: "Barrick does face a potential problem however in the event the contango turns negative. ... Backwardation represents the biggest threat to the Barrick Program [of spot deferreds] because the new contract price declines on each re-pricing date when there is backwardation." But because "the gold market is almost never in backwardation," he concludes: "It is therefore safe to assume that the contango will be positive on re-pricing dates."

Safe as this assumption may be under normal free market conditions, does it remain safe after years of central bank manipulation of gold prices and lease rates? And in the event gold goes into backwardation, what would be the consequences not just for Barrick but for others in the gold market as well?

The essay that introduced this website, War against Gold: Central Banks Fight for Japan, addressed the consequences of yen gold prices going into backwardation when yen interest rates were dramatically lowered in 1995, and further speculated that this development may well have triggered the continuing manipulation of gold prices that began in earnest at about that time. But gold is typically priced in dollars worldwide, and dollar gold prices in backwardation would present a far more serious problem, particularly under current circumstances.

Falling U.S. interest rates have already reduced the contango to the point where there is little incentive for producers to engage in forward sales, for fabricators to borrow, or for anyone to borrow gold instead of dollars. However, backwardation of dollar gold prices would reverse the incentives, putting pressure on the spot market as producers, fabricators and other gold borrowers closed gold loans and moved to cheaper dollar financing. This surge in demand would likely operate on the short physical position to send gold prices and lease rates skyrocketing just as happened after the Washington Agreement, and in the process unmask the fundamental weakness in the structure of modern gold banking.

In the currency markets, rising interest rates are a two-edged sword, penalizing borrowers but rewarding lenders. Move rates high enough, and hard cash migrates out from under mattresses and into bank deposits. Currencies, at least until they descend to the status of party favors or wallpaper, never stray too far from the banking system. In his presentation at the GATA summit in Durban, Frank Veneroso made this key point about gold:

Now, almost all commodities have an income elasticity of less than unity; in other words, they almost all have a declining intensity of use over the long run, at least in modern economies. BUT NOT GOLD. Excluding the monetary use of gold and focusing only on jewelry, on electronics, and the like, if you look at 200 years of data until 1997 what you find is that gold has an income elasticity in excess of unity. That is, demand rises more rapidly than global income over periods in which the gold price is constant in real terms.

For nearly a decade, by lending gold at concessionary rates and capping gold prices, the central banks have fed primarily non-monetary or commodity demand, largely from the third world, not western investment demand. In the process, the central banks have let the bullion banks engage in gold banking without maintaining prudent reserves, as for example the BIS does. Even worse, the central banks have allowed the entire gold banking system to spill a large amount of its physical reserves into non-monetary or commodity uses -- areas from which their retrieval by the banking system is far more difficult.

Outside of the central banks themselves, there is now no obvious large pool of investment gold that can readily be mobilized and quickly attracted back into the bullion banks through higher lease rates. The bullion banks could of course buy gold, but that entails using their own capital and would just add to upward pressure on prices. Sharply higher prices, even if they draw back significant tonnages of gold from price-sensitive holders in India and elsewhere, would also risk awakening previously dormant investment demand in western countries, not to mention triggering a spike in lease rates.

Current lease rates are low because they have to be. Sir Alan and his court at the BIS have built modern gold banking on Dr. Murenbeeld's assumption: dollar gold prices always in contango, which requires that lease rates be held below dollar interest rates. When dollar interest rates fell below those on euros, exchange rates for the euro expressed in dollars went into backwardation (as they typically are for the Canadian dollar and the British pound) without causing any major disturbance in the currency or financial markets. Dollar gold prices in backwardation, however, would threaten a financial Armageddon, and that is the principal difference between currencies and gold as they are traded and arbitraged today in world markets.

Checkmate. Sharply rising OTC gold derivatives in the face of reduced incentives for gold lending or borrowing, and against falling LBMA volumes and declining open interest in COMEX gold options, send an ominous message. They suggest that the bullion banks have been unable to wind down their pyramid of gold derivatives in an orderly manner as contangos have narrowed, and that the central banks are locked into rolling over (or even adding to) their gold leases at rates that no longer compensate -- if they ever did -- for the real risk assumed. It is a message that appears confirmed by recent staff cutbacks at several bullion banks and the withdrawal of others from the business completely.

The free market alternative to gold in backwardation is higher U.S. interest rates, possibly much higher if lease rates are allowed to move to levels that not only fully compensate for risk but also are sufficient to draw gold back into the banks from non-monetary uses to which so much of it has escaped. If tightness in the gold market cannot be remedied through higher lease rates because neither backwardation nor higher dollar rates are acceptable policy choices, the only means left for restoring market balance is higher prices.

Absent higher lease rates, the gold leasing market can remain functional for only so long as the central banks continue to support it at non-economic rates or until they run out of gold. Without a gold leasing market, forward and futures markets for gold could no longer operate on the basis of relative interest rates, as they have and as forward currency markets do. Instead, forward prices on gold would have to be set on the basis of external factors, just as forward prices for oil and other commodities are.

Any transition in the forward gold markets from the currency/relative interest rate model to the ordinary commodity model is difficult to envisage without an intervening period of effective closure, including a cessation of trading in the COMEX gold contract. What is more, upon reopening in commodity mode, the forward gold markets would likely be much smaller than when they were operating in banking or currency mode. Barrick concedes that its ability to roll over its spot deferreds is contingent on "the existence of a gold pricing market." According to Dr. Murenbeeld, the ability to roll terminates "if the bullion bank can't borrow any more gold anywhere." These contractual provisions deal with what are no longer remote theoretical contingencies, particularly in the event of a non-linear upward explosion in gold prices.

Non-linear events are the Achilles' heel of derivatives and not uncommonly grounds for unprecedented exercises in the arrogance of power. If gold pushes Sir Alan's dollar and interest rate policies too close to checkmate, he can upset the board and send most paper gold instruments to the nether regions. But he is not an alchemist. Perhaps that explains his recent speech to the Council on Foreign Relations acknowledging hidden dangers in derivatives (www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2002/20021119/default.htm), instruments he normally praises as effective insurance against financial risk but that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger describe as financial sewage. Mais alors, Sir Alan ne se prend jamais pour de la petite merde.